As the age of disaggregated, cloud-stored music flowered, the album cover almost died. There was a depressing time, back at the start of the new millennium, when it seemed the future of music lay with tiny little MP3 tracks downloaded from the Web. Fortunately, that didn’t happen.

Albums are a thing again. Memorabilia has emerged as a money spinner in the music industry value-chain. Led by DJs, hipsters and anoraks, vinyl has returned from the grave. Vinyl sales rose 32% in 2015. Since an album curates and conveys a musician’s vision far better than individual tracks can, this resurrection is welcome.

But the cover art is important too. Sometimes it reveals almost nothing about the music, rather illuminating the society it sprung from, revealing unexpected stories of people, art forms and struggles.

American music writer Lara Pellegrinelli grew up intrigued by the models who decorated her family’s jazz LP covers. When, for example, American jazz pianist Erroll Garner’s “The Most Happy Piano” was fronted by a glamorous redhead:

Narrowed blue eyes peered from under thin, arched brows… The record jacket squarely framed the slender face, with a teasing hint of bare shoulders below.

But as Pellegrinelli’s interviews about the attitudes of the record industry revealed,

if Erroll Garner really had been a gorgeous redhead, the cover would have been as far as she’d get.

That same tantalising sense of a history as much hidden as disclosed by the pictures permeates the Alliance Francaise “September Jive” Musical Graphics exhibition in Johannesburg. Curators Rob Allingham, Siemon Allen, Molemo Moiloa and Lara Preston have assembled and displayed chronologically 150 covers of South African records, dating from 1957 to the present. The selection was guided by both aesthetics and the musical choices of industry role-players, whose portraits form a parallel display.

Apart from provoking a serious case of platter envy in any collector – saxophonist, composer and pianist Dudu Pukwana’s 1969 hard to find debut with “The Spears”, anybody? – these 12-inch cards can be shuffled in a range of ways, to unfold multiple narratives. Collector Siemon Allen’s magical 2013 Recording History installation at the Iziko Slave Lodge in Cape Town had already made that point, but never found gallery space in Johannesburg.

Bitter, committed riffing

There are, for example, at least three “white” histories on display: religious, military and oppositional.

Oppositional work ranges from the bitter, committed riffing on leftwing themes in compilations such as the anti-conscription, “Forces Favourites”, or anti-establishment Afrikaner punk-rock by Johannes Kerkorrel and his peers, to the slightly comic attempts of aspiring bohemians at smuggling the Swinging Sixties into “verkrampte” (reactionary) South Africa. Hennie Bekker’s 1971 “Turn On”, for example, shows a torrent of psychedelic images pouring from a crudely superimposed galvanised tap.

The military history is the most distasteful: deeply racist, sexist and disgendered. It is simultaneously titillating and coy about both female bodies and guns. There was an epidemic disappearance in South Africa of white female nipples during the 1960s and 1970s. Michael Drewett, scholar of this manipulation of desires during the era of “our boys on the border”, will lecture during the September Jive season.

Perhaps the most intriguing narrative shows how a common visual language around jazz coalesced among the community of black artists in 1970s Johannesburg. Some of these painters became famous. Some are barely known outside collectors’ circles.

But just as the official history of choral music has erased the tradition of workers’ choirs from its syllabus, so official art history seems to have little place for these artists or this genre of subject matter.

Let’s talk about all that jazziness

For the past two months, we have preferred to discuss the jazziness of Henri Matisse over the jazziness of the South African artists Dumile Feni or Lefifi Tladi. Let alone discussing the artists on display here: Hargreaves Ntukwana and Zulu Bidi.

The art of Ntukwana and Bidi came from a community and reflected a legacy. In another kind of exhibition we might have grouped it together and used the term “school”. The places where such artists studied, such as Cecil Skotness’s Polly Street Art Centre, built on an urban black visual arts tradition that can be traced back at least to John Koenakeefe Mohl’s “White Studio” in Johannesburg’s Sophiatown suburb in the 1940s.

Both Polly Street and the White Studio permitted walk-in students. We learn from memoirs about the rich cross-fertilisation among practitioners of different genres even after apartheid removed and separated artistic communities. But students outnumbered the formally enrolled: those who studied shared skills with their peers, as in every roots creative community. Some members of those circles travelled, studied and exhibited abroad, and gained fame: Feni, Tladi, Ernest Mancoba and more. Ntukwana eventually made it to the Artists’ Colony in Toledo, Spain.

Others stayed home, putting art or music on the back burner to earn for their families. The occasional album cover commission must have provided a welcome opportunity to reawaken that side of their creativity. These covers should be looked on as a legitimate part of their opus, since other creative opportunities under apartheid were so limited, stereotyped and censored.

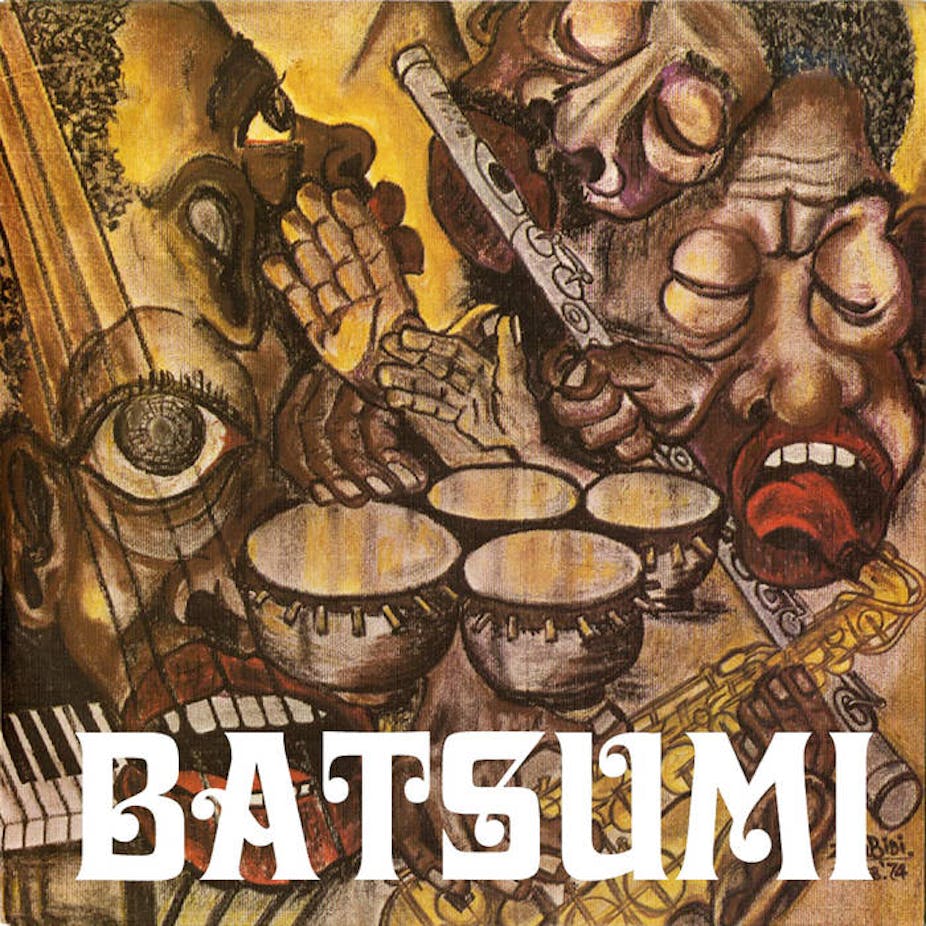

Both Ntukwana and Bidi were musicians: the former had played in the pit band of the musical “King Kong”; the latter was bassist with jazz band Batsumi, and sideman for countless other bands.

But those skeletal biographies make up much of what we know about them – in Bidi’s case, almost all of it. The historical record is incomplete. We can only speculate about motives and inspirations and have no complete catalogues of works. That matters for several reasons, not merely completeness.

Without such information, it’s hard to add this work to the curriculum. Further, the lacunae handicap the history not only of art, but also of jazz.

A distinctive visual language about South African music was being shaped by these artists and their peers: a particular way of engaging with the music in images, analogous to the way that the jazz appreciation societies developed a kinetic language for engaging with the music through steps. We cannot accurately trace the development of that language through such a partial record.

All the artists building this visual vocabulary paved the road that has brought us to today’s jazz cover art from, for example, Mzwandile Buthelezi. He is his own man, but he did not emerge, fully formed, from nowhere. More postgraduate research into these lives and works is desperately needed, so that Ntukwana, Bidi – and their still unknown peers – become more than signatures on the corner of an LP sleeve.