Sydney loves to talk about food, and the housing market. But rarely do we talk about the threat that housing poses to the resilience of Sydney’s food system.

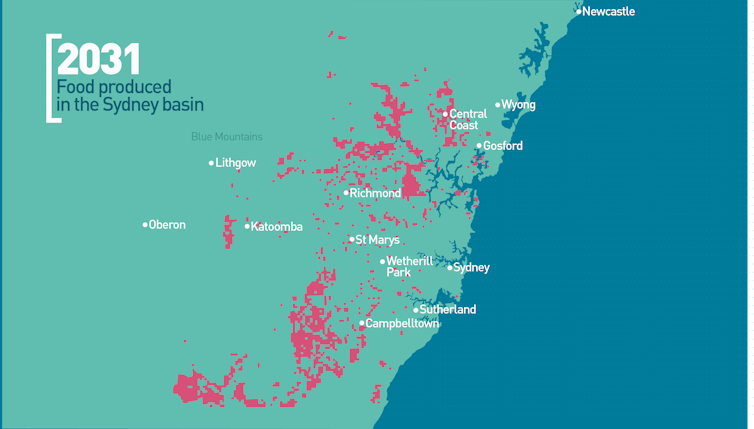

If we continue along the path we’re on, Sydney stands to lose more than 90% of its current fresh vegetable production. Total food production could drop by 60% and the city’s supply of food from within the basin could drop from 20% of total food demand to a mere 6%.

Like most Australian cities, Sydney is facing an influx of people – 1.6 million new residents are expected over the next 15 years.

Competing priorities for land are compounded by this growing population, as well as by planning laws that favour development over agriculture – not to mention a changing climate. Cities worldwide are facing the same issues as we try to feed a growing population with limited resources.

Protecting farmers

Sydney’s fertile soils are being paved over at a rapid rate. Large portions of areas that currently grow Sydney’s fresh produce are earmarked for release for housing development.

Currently, the planning system does not prioritise agriculture as a land use, meaning urban sprawl into potential farmland continues relatively unchecked. Instead, planning tends to focus on whichever use has the greatest economic value.

In an overheated housing market such as Sydney’s, this tends to mean agricultural land is allowed to be rezoned for houses or other higher-value land uses.

As city land prices rise, more people are moving further out for a “tree change”. Lower land prices on the city’s fringe allow families to purchase large homes and lots at a lower price than in the city.

But many of these new rural residents don’t like the early morning sound of tractors and the smell of manure on neighbouring farms, and make nuisance complaints to their local council. These complaints often result in tough operating restrictions being placed on farmers’ activities, such as limits on hours of operation and types of fertiliser that can be used.

These restrictions are introduced by councils to appease local residents and are in accordance with noise pollution laws designed for urban residential areas. But they can have significant impacts on farm viability. In several instances, such restrictions have pushed marginal farms into the red, eventually forcing farmers off their land and out of the basin.

The New South Wales government is interested in taking steps to ameliorate this problem, as demonstrated through its recently tabled Right to Farm policy. This seeks to ensure that farmers’ right to operate their business is protected against nuisance complaints.

Why growing food in Sydney is important

There are enormous benefits to growing fresh food in the Sydney basin – and, indeed, near any city. Perishable foods such as Asian greens and eggs can be grown close to market, reducing spoilage, waste and food miles, and buffering against spikes in fuel prices.

Agriculture and food processing are labour-intensive, providing significant local job opportunities. In fact, the benefit of Sydney’s agriculture to the economy is estimated at upwards of A$4.5 billion. This includes jobs in storage, processing, transport and retail.

A changing climate will mean many of Australia’s important foodbowls, such as the Murray-Darling Basin, are likely to be more vulnerable to droughts and floods. Sydney’s higher rainfall and fertile soils will become even more suitable for growing food, meaning their importance to Sydney’s food supply will grow.

Farms on the fringes of our city will help buffer the city against the impacts of climate change, by cooling the city and helping wildlife move between habitat.

Food produced in close proximity to the city can also be fertilised by nutrients and organics in urban food waste, garden waste and wastewater. Accounting for these sources, Sydney actually has 15 times more phosphorus supply than agricultural demand. That means local food systems can better buffer against the growing global threat of phosphorus fertiliser scarcity, a threat that could lead to further fertiliser price spikes and supply disruptions.

Sydney’s farms also help buffer the city against disruptions to food supply. For example, if a bushfire or fuel shortage cut transport routes into Sydney, the city would have only two days’ stock of fresh produce.

Our research shows that in the face of dramatically increasing population, Sydney stands to lose these benefits.

A similar study in Melbourne found their city’s foodbowl could plummet from meeting 41% of Melburnians’ food demand to 20%.

Unlike Melbourne, Sydney is geographically constrained by mountains on one side and ocean on the other, meaning there is nowhere for agricultural production in the basin to go. Our agricultural production is literally being chased to the hills – and this at a time when we face the challenge of feeding over a million extra mouths.

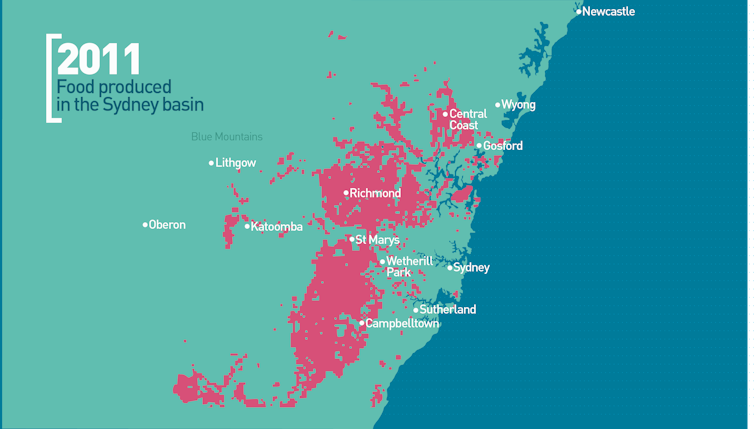

We’ve mapped Sydney’s current and future food production. The pink areas of the images below are areas where food is produced. As the maps indicate, the areas producing food in 2031 will dramatically decrease if we continue along the path we’re on.

A better food future

Our city plans need to value and better protect agriculture from urban sprawl. Planners need to make decisions based on evidence to balance competing land uses.

These decisions need to take account of the full suite of values and benefits we gain from Sydney farmers, not just the economic gains we stand to achieve by converting the land to houses.

Farmers in the basin need better commercial conditions, a fair price for commodities, land security and support from other residents.

Sydneysiders need access to affordable housing, jobs and infrastructure.

But, equally, they need access to nutritious and affordable food, reversing the high rate of obesity and diabetes, and “food deserts” without access to groceries particularly prevalent in Western Sydney.

Through increased awareness and accessibility, food shoppers can also support local food producers, increasing the resilience of Sydney’s food system and simultaneously reducing the environmental footprint of food.

However, strategic policies and plans are needed to ensure that agriculture is valued and prioritised as an important land use and economic activity within our city, to ensure that buying local food is a choice that consumers can make in future.