Last week the world stopped to watch as the black disc of Venus inched its way across the face of the sun.

But beyond the transits that capture our attention roughly twice per century, Venus has always held a special place in the human imagination, not least because of its association with the arts of love.

It’s also the most visible of all the planets in the night sky (and accounts for a large proportion of alleged UFO sightings).

Now, more than 25 years after the last spacecraft landed on Venus, there are plans to go back.

Twisted sister

Venus’ mass, gravity and volume are very similar to that of Earth and more than any other planet, Venus is considered critical in understanding the evolution of Earth.

But there are some major differences between the two planets, including:

- Venus rotates clockwise on its axis (it’s the only planet in our solar system, besides Uranus, that does so)

- Venus’ surface is obscured by layers of thick, impenetrable cloud.

Before the modern era of space exploration, no-one knew what we might find on Venus. Could those thick clouds have been hiding the first evidence of life outside Earth?

Early speculations painted Venus as a world of dry dusty mountains, oceans of carbonic acid, and pools of molten metal. Others imagined a warm, swampy world that resembled Palaeozoic Earth (from 542 to 251m years ago).

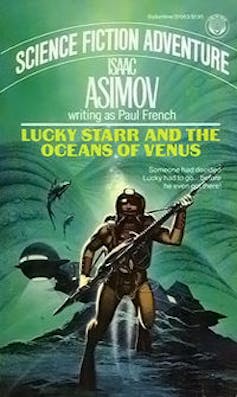

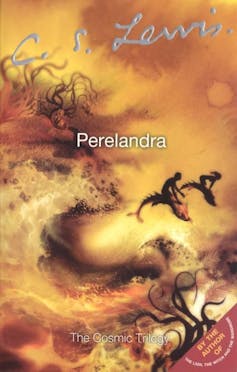

Venus appeared in literary fiction too. In his 1943 novel Voyage to Venus (also known as Perelandra), C.S. Lewis imagined Venus as a new Eden of fragrant floating islands covered in exotic and delicious fruit. In Lucky Starr and the Oceans of Venus (1954) Isaac Asimov imagined telepathic frogs swimming in Venus’ warm oceans.

But when the first missions to Venus returned data, dreams of life on our sister planet were all but dashed.

Sapphires, diamonds and Daleks

Flyby missions, such as that of NASA’s Mariner 2 in 1962, suggested Venus might have a surface temperature of around 430°C and pressure of around 100 atmospheres (atm) (that is, 100 times the pressure at sea level on Earth), but these figures seemed scarcely believable.

Throughout the 1960s, the USSR launched a series of Venera spacecraft that were crushed as they descended through the atmosphere. Each failure was part of the learning curve.

Finally, in 1970, a craft designed to withstand pressures of up to 180 atm, Venera 7, made its way safely to the surface of Venus and finally sent some data home. The seemingly impossible surface temperatures and pressure were confirmed.

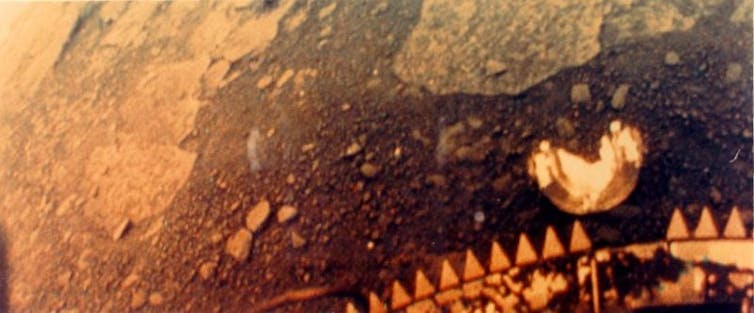

Venera 9 and 10, in 1975, returned the first pictures of the surface. In these extraordinary images (see below), we see a field of flat rocks, with the curve of the spacecraft’s shock absorber visible on the lower edge of the photo.

The perspective, as if a person is looking down at their own feet, gives the photographs a personal feeling. The Veneras looked eerily like the Daleks of Dr Who fame – they almost seemed as if they could start moving of their own volition.

Pioneer Venus has been the only US mission to land on Venus. In 1978, a bus delivered one large probe (called Large), and three small probes (North, Day and Night) to the surface. Like the successful Veneras, the scientific instruments in the Pioneer Venus probes were shielded from high temperatures and pressure by a titanium shell.

To allow the craft’s instruments to see outside, Large was fitted with four sapphire windows and one diamond window. The small probes had two diamond windows each.

The last missions to land on Venus were the USSR’s Vega 1 and Vega 2 probes, released by rockets on their way to a rendezvous with Halley’s Comet. Launched in 1984, both Vegas successfully landed on Venus in 1985 and returned data.

Surviving the surface

The pictures taken by the landing missions and other orbital and flyby missions – such as the European Space Agency’s Venus Express which has been in orbit around Venus since 2006 – revealed a fierce environment with the most corrosive upper atmosphere in the solar system.

Little wonder then that the data transmission from craft that landed on Venus ceased after just a couple of hours.

But could the Venus landers and probes have survived the horrendous surface conditions to this day? It seems quite possible.

There is no water on the surface and surface winds move at human walking pace. As a result, erosion processes are so slow that craters a few million years old appear fresh.

Droplets of sulphuric acid from the upper atmosphere evaporate as the temperature rises towards the surface, rarely surviving below about 25km. Titanium melts at 1,662°C, diamond at 3,550°C and sapphire at 2,040°C, well above the average 460°C conditions at the surface.

Based on this information, there seems no reason why archaeologists of the future should not find the titanium components of the Veneras, Vegas, and the Large, North, Day and Night probes intact, the diamond and sapphire eyes of the last of these gazing sightlessly at the dull brown terrain.

These spacecraft represent an evolution and adaptation to increasingly more accurate information. Each set of returned data enabled the design of spacecraft more suited to surviving Venusian conditions.

Return to the planet of love

Nearly 25 years later, there are plans to return to Venus. Just last month, NASA finished building an Extreme Environments chamber at its Glenn Research Centre in Cleveland. The chamber will test the next generation of landers and rovers at Venusian temperatures and pressures, and with toxic cocktails of acids.

These new spacecraft will hopefully have the capacity to transmit data for sustained periods of time. And if they can survive on Venus, they can withstand conditions anywhere else in the solar system.

The planned Venus mission is part of NASA’s Revolutionary Aerospace Systems Concepts program:

Of course, whether any new mission is launched will depend on the increasingly precarious funding situation that NASA has battled with over the last decade.

So, might new missions find evidence of life after all? Well, that remains very unlikely but earlier this year it appeared we might have missed something big from a previous mission.

Analysing the films from Venera 13 (launched in 1981), Russian scientist Leonid Ksanfomaliti reported a scorpion-like creature moving around at the foot of the spacecraft.

Sadly, the creatured turned out to be a fallen lens cap and the movement he had seen was the result of digital noise.

But we shouldn’t give up hope entirely. According to controversial astrobiologist Chandra Wickramasinghe, last week’s transit of Venus saw solar winds lift sulphur-loving microbes and bacteria out of Venus’ upper atmosphere and towards Earth, where they were captured by clouds and will eventually fall to Earth in rain.

Organisms which live in sulphurous, high-temperature thermal vents on the ocean floor are well known on Earth, so sulphur-based life forms in Venus’ upper atmosphere are not out of the question.

Questions of Venusian life aside, what sort of new information would a new mission to Venus actually yield?

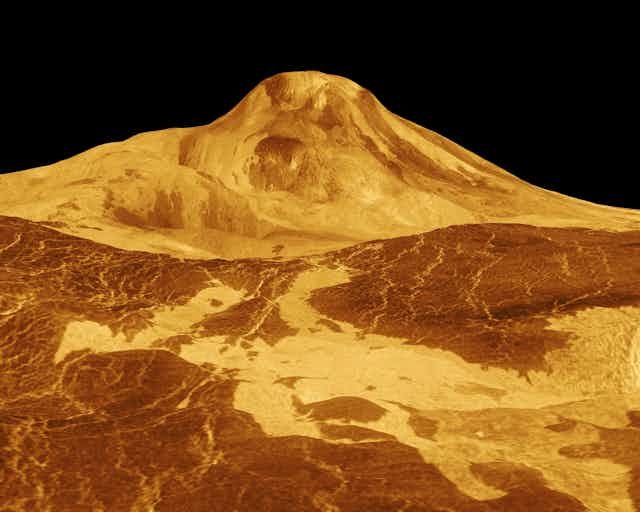

Well, we learned from earlier missions that Venus probably once had oceans and a more congenial climate. But something happened to turn our twin sister into a greenhouse hell. It may have been volcanic activity – Venus, it turns out, is not as seismically inert as was once thought.

What we want to know now is whether such an event could happen to Earth too.

Australian planetary scientist Daniel Cotton from the University of New South Wales is making progress in this area by studying the distribution of carbon monoxide in the lower atmosphere of Venus.

But there’s only so much we can do from Earth – it’s time to send spacecraft to the surface of Venus once more.

In the meantime, if Chandra Wickramasinghe is right, then we can all experience the essence of the planet of love just by standing in the rain.