These are wild times for the management and governance of the internet, as is clear from the ruling that came out of the US this week. In a victory for the private sector, the Federal Communications Commission was thwarted in its attempts to force network provider Verizon from treating all customers equally.

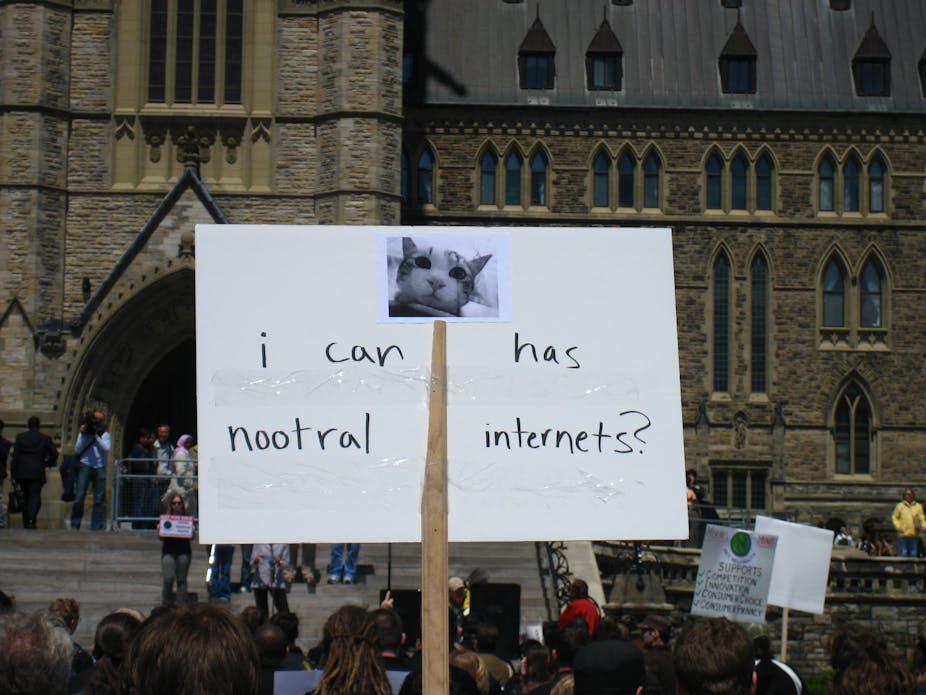

The decision provoked a storm about equitable access to online services, known as network neutrality. Although there is talk of an appeal against the Verizon ruling, this is an issue that will have significant implications for every one of us and it’s unlikely to go away.

Network neutrality is not simply a technical issue – it’s about social, economic, cultural and political preferences and consequently, it’s important to be aware of what changes are proposed and how they could affect the way we use online services.

What are we fighting for?

When data flows across the internet, it is broken up into smaller “packets” which travel through the fastest possible route to any given destination. Upon arrival, these packets are reassembled so that the file, email or video is accessible on our own computer or device.

Network neutrality typically refers to the transport of these data packets without prejudice. In a neutral network, all packets are transferred at the same speed without preference being given to some packets over others. No one can pay more to have their data privileged while others are left with a slow, second rate connection.

The Verizon ruling essentially does away with this principle and has therefore raised concerns about a market emerging for internet access. An internet movie streaming service could, for example pay a network provider to privilege its data so that it can provide a more reliable streaming service.

And because the internet has become such an important tool in areas such as education and development, the emergence of a two-lane highway has implications that go well beyond simple marketplace calculations about who foots the bill. Network neutrality sounds egalitarian and democratic but there are complicating factors that make it a much more difficult issue than many on either side of the debate would like to admit.

The US is different

In the US, where internet infrastructure is lagging behind many other developed nations, the reliance on the private sector to build networks and improve speed and access means that marketplace calculations about internet access take on added significance.

Companies such as Verizon argue they simply can’t make the profits they need to justify the amount they spend on infrastructure without restructuring their commercial opportunities, which begins with doing away with network neutrality.

These network providers think the likes of Google, eBay and Amazon are cashing in on their platforms without having to invest. The dot com start-up economy is based on brains, creativity and innovation, not capital investment, and that is an irritation for Verizon.

There are two obvious alternative models when it comes to paying for the pipe. Either the individual end user pays (some say we already do) or the companies that offer online services do.

Verizon would like hugely profitable companies such as Google and Facebook to pay for running their businesses across the internet. While there is some sense in that, the fear is that it would seriously stifle the extraordinary innovation we’re witnessing right now in the sector.

Google and Facebook, if pressed, would pay. But what about the next Google or Facebook that is yet to emerge from the garage or the college dorm? Tim Berners Lee, the UK scientist who invented the World Wide Web has repeatedly said that if he had charged for using the web in the first place, there simply would be no web.

Streaming sends us to the brink

Although the debate about privileging data on the internet goes back to the first years of privatisation and commercialisation in the mid 1990s, the rapid escalation in streaming media content has exacerbated the problem.

Streaming media packets need to arrive in time and in sequence. If an email takes a little longer to be reassembled and appear in our inbox, there is no impact on the quality of the experience for us. The same cannot be said for watching video online or listening to an audio file. If those packets don’t come in order and in time, we get poor playback quality and we generally blame that on our provider.

This is Verizon’s point. Telcos argue they need to be able to manage the network or privilege certain packets over others in order to stop our media content from stalling. That’s a step that many would concede as reasonable or even desirable and indeed, it already happens in some contexts.

Others, however, see this as the thin edge of a very big and irreversible wedge. The next step could be for network providers to privilege data that engages with services and applications they own or favour – and that would be the end of choice online. Why allow Skype traffic through when you provide a similar service? Why allow users to watch BBC iPlayer when a deal with Channel 4 would yield more profit?

In an ideal world (and in some lucky countries like South Korea and Estonia) the government also invests in or stimulates investment in internet infrastructure to ease this pressure on private telcos. Though judging from the way the ambitious Australian National Broadband Network has been stopped in its tracks by a change in federal power, that’s not a perfect solution either.

It’s important to remember that there is nothing determined about the internet. It doesn’t have to be neutral, it doesn’t have to be dominated by commercial concerns and it doesn’t have to be as insecure as it currently is. These are not technologically determined features of the internet, they’re choices that we make all the time. Or at least, they’re choices that are being made on our behalf. It’s a mistake to underestimate the role of politics in the internet.