Ten years ago, PayPal founder Peter Thiel condensed the growing sense of disappointment in new technologies down to just nine words. “We wanted flying cars,” he wrote, “instead we got 140 characters”.

That these words still ring true a decade later shows just how far short of expectations new technologies have fallen. To drive growth in a post-pandemic world, we should remember that real economic progress has in the past been driven by hard science – not flashy consumer gadgetry.

For years, hopes for productivity growth have been pinned on “Fourth Industrial Revolution” (4IR) technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and 3D-printing.

But, in contrast to previous industrial revolutions, recent advances in digital technology have not resulted in the expected boost in productivity. Labour productivity growth has been stagnating since the 1970s. In the UK, it’s actually at its slowest rate in 200 years.

Stagnating productivity has not gone unnoticed. Having banged the drum of the Fourth Industrial Revolution since 2016, the World Economic Forum has now changed its narrative to the “Great Reset”. No doubt this change reflects new economic realities wrought by the pandemic, but it’s also a silent admission that the 4IR has dramatically under-delivered on its promises of productivity and prosperity.

Why? First, dominant firms that possess 4IR technologies are hindering their diffusion by leveraging their technological advantage to further entrench their dominance and reduce competition.

This happens because software technology, which is subject to large fixed costs but low marginal costs, enables larger firms to develop better-quality products and services than their smaller rivals. That leaves smaller firms facing high obstacles and low benefits when considering the adoption of 4IR technologies. Many elect simply to continue without them.

This means that 4IR technologies are not diffusing fast enough. The gap between the “technology haves and have nots” in the corporate world is widening. A recent study also found that this gap is widening between rich countries and poor countries. When few companies have access to 3D printers, robots, or cutting-edge AI, there are fewer actors to leverage such technologies to the point at which productivity will increase across the board.

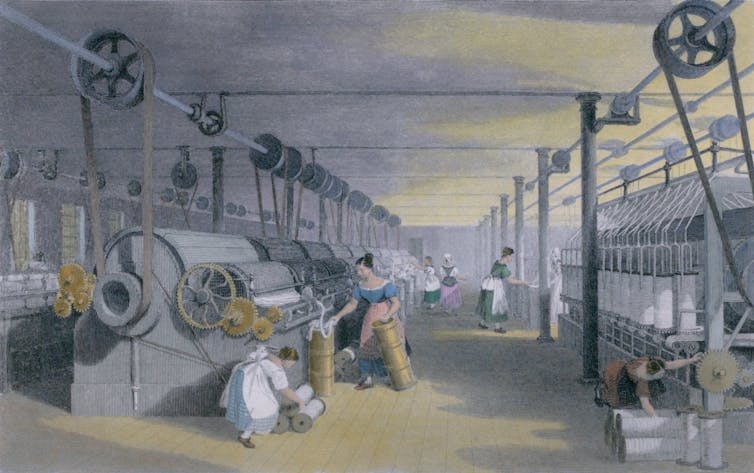

It was general-purpose technologies – such as steam engines and the electric dynamo – that powered change in previous industrial revolutions. At present, it remains unclear whether 4IR technologies can do the same.

For example, AI has been of little value against the pandemic, failing to contribute constructively to solving the biggest problem of a generation. 4IR technology is stuck in what research firm Gartner call the “trough of disillusionment” – a state of disappointment we feel when technologies fail to live up to the hype.

Shifting investments

This “technology problem” has been well documented. New digital technologies are often found to deliver diminishing returns over time, especially once “low-hanging fruit” have been plucked, leaving only more ambitious, costly, and risky projects up for grabs.

To avoid a technology problem, we need to invest in science that delivers general-purpose technologies, and technologies that deliver real scientific progress. To get there, we’ll need new strategies in research and investment once the pandemic subsides.

For instance, the vast majority of investment in digital technologies is currently driven by venture capitalists out to score quick returns on start-ups that can be scaled fast. As a result, technologies that require more development time – but that are most likely to lead to new breakthroughs – tend to be starved of funds.

This investment trend can leave crucial industries and technologies without the necessary funds to advance and innovate. For instance, venture capital (VC) funding into medical instrument technologies – vital for the continuing fight against pandemics – declined by over 50% between 2003 and 2017. Elsewhere, the VC market for technologies to combat climate change is in a crisis.

With markets allocating insufficient funding to technologies that might help tackle our grand global challenges, controversial arguments are now being made for mission-oriented innovation policies, which would entail an “entrepreneurial state” leading the charge towards key technologies.

Back to the lab

Many doubt this “creationist” view of innovation whereby the state can lead innovation, and argue instead that innovation is a bottom-up process. Whether innovation is creationist or bottom-up, we need to rethink our institutional frameworks for doing science, and start with the role of universities.

According to a growing chorus of commentators, fundamental physics, which delivered virtually all of the technologies underpinning earlier industrial revolutions, has been stagnating for years. This stagnation is now accompanied by a rise in anti-science movements that reject scientific knowledge on climate change, vaccine safety, and even the shape of the earth. At the same time, academic freedom is under threat.

University science has also become encumbered by unhelpful administrative incentives, box-ticking, and “a focus on incremental studies rather than more ambitious projects which are likely to fail, but might lead to more exciting breakthroughs”. Overcoming these obstacles should be a leading priority as we develop post-pandemic research and innovation policies.

How we reset

The Fourth Industrial Revolution never really got off the ground — largely due to human flaws in distribution, investment and research which restricted the diffusion of its technologies and skewed investment into technologies with less meaningful economic impact.

The Great Reset, like the Fourth Industrial Revolution, reads like a Hollywood script. To move beyond headline-grabbing science fiction and glitzy gadgetry, we need a real “back-to-basics” revolution — in the kind of science-plus-risk-taking that delivered economic prosperity in the past. For a start, this will demand more entrepreneurial university research projects that may well fail, but which might break new ground, too.