In several speeches of late, Prime Minister Scott Morrison insisted with a straight face that Australia is doing its bit on climate change. The claim was swiftly and thoroughly debunked. The truth is that the Morrison government is piggybacking on the efforts of others, to varying degrees of success.

We saw it in electricity generation, where the federal government has rejected a string of schemes to reduce emissions. Nonetheless the electricity sector is getting cleaner as ageing coal-fired power stations are replaced by renewables. This outcome owes nothing to federal government action. It reflects state government policies and the residual effects of the previous Labor government’s Renewable Energy Target, and public pressure that forced banks and insurance companies to stop supporting fossil fuels.

In the transport sector, after decades of inaction, the government rejected recommendations from the Climate Change Authority to impose fuel efficiency standards on passenger vehicles, leaving Australia as the only OECD country without such standards. It has similarly derided action to promote the use of electric vehicles.

Instead, the Coalition is relying on the hope that carbon dioxide emission rates of Australia’s new passenger vehicle fleet will reduce over time without any effort by governments, because vehicle emissions legislation overseas, where Australia’s cars are made, is delivering technological improvements. Official projections state that some, but not all, of this improvement will flow through to Australia.

Unfortunately, this assumption is not reliable. New research shows that for the first time, fuel efficiency in Australia is getting worse, not better. In the absence of positive action from governments, transport emissions will continue to grow, and even accelerate.

A nation of car lovers, and carbon belchers

Total road travel in Australia rose from 181 billion km in 2000 to 255 billion km in 2018 - a 41% increase.

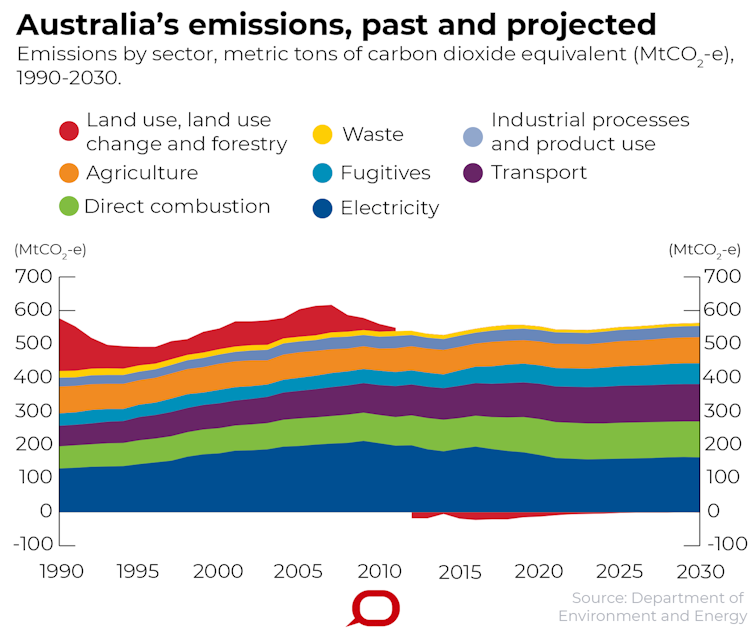

Total CO₂ emissions from road transport increased by 31% between 2000 and 2017, rising from 16% of total emissions in 2000 to 22% in 2017. With no action, transport emissions are projected to reach 111 million tonnes of CO₂ by 2030.

Emissions have grown more slowly than kilometres travelled, which suggests that improvements in fuel efficiency have partially mitigated the effect of increased travel. Reducing emissions from transport will require a stronger decline in emissions intensity (CO₂ emissions per kilometre travelled) from our vehicles. Under current policies, this will not happen.

Our assumptions are all wrong

A recent analysis by Transport Energy/Emission Research (TER) found the actual emissions intensity of new Australian passenger vehicles has stabilised and likely increased in recent years.

This finding directly contradicts projections that emissions intensity will fall without government intervention.

The chart below shows the average fleet emission rates officially reported in Europe, the US and Japan, and based on laboratory tests. When compared to these jurisdictions, Australia’s new passenger vehicles have significantly higher average CO₂ emission rates, and thus fuel consumption, than other countries, but all show a decline.

Official new private vehicle fleet average CO₂ emission rates 2000-17

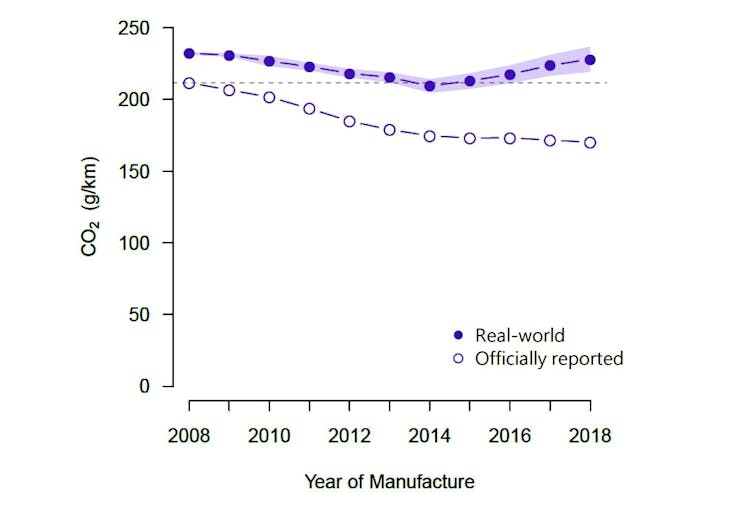

Unfortunately, real-world emissions and fuel consumption deviate substantially – and increasingly – from laboratory tests that are used to produce the officially reported CO₂ figures. This discrepancy is often referred to as “the gap”. So in reality, the reduction in CO₂ emission rates is not as large as official laboratory results suggest.

There are multiple reasons for this gap, such as the laboratory test protocol itself, and strategies used by car manufacturers -and allowed by the test - to achieve lower emissions in laboratory conditions.

TER corrected the official Australian figures to reflect real world emissions. It found that carbon emission intensity stopped declining around 2014 and is now increasing. This suggests that, for the first time, fuel efficiency is no longer improving and is actually getting worse.

Official vs real-world CO₂ emission rates for Australia’s new private vehicle fleet

The upshot is that total CO₂ emissions from road transport are increasing, and will accelerate in the future.

The TER study identified the likely reasons for this: increased sales of heavy vehicles, such as four-wheel drives, and diesel cars. The latter may have a reputation for fuel efficiency, but they still emit, on average, about 10% more CO₂ than petrol cars. Australian diesel cars are, on average, about 40% heavier than petrol cars, and have 15% higher engine capacity.

The road ahead

The worsening picture in road transport emissions will increasingly drag down Australia’s efforts to meet its modest climate goals set in Paris - even with the accounting tricks the government plans to deploy to reduce the task. Of course it also means Australia is far less likely to make the much sharper emissions reductions needed by all nations to stabilise the global climate.

What can be done about this? The most obvious first step is to implement mandatory fuel efficiency or vehicle emission standards. This policy, fundamental in other countries, would significantly lower weekly fuel costs for vehicle owners.

Read more: Clean, green machines: the truth about electric vehicle emissions

Second, a rapid shift to electric cars will help, and increasingly so as the electricity supply transitions to renewables. Deep emission cuts are then possible.

The third is to provide better information about actual emissions. This could be achieved by restoring the large testing programs conducted in Australia up to 2008, involving hundreds of Australian vehicles over different real-world Australian test cycles which generated large databases of raw measurements.

For the moment, Australia’s national greenhouse gas emissions strategy seems to be: do nothing, rely on the work of industry, state governments and other nations, and hope that nobody notices. But climate change is not going away. Dodging it now will only increase the costs we accumulate in the long run.