On Tuesday November 11, 1975, I was teaching at Balmain High School on Terry Street, Balmain. At the time, Balmain was still a predominantly working-class suburb. Terry Street also happened to be where the serving Governor General and Whitlam Government appointee, Sir John Kerr, had once lived in a modest worker’s cottage.

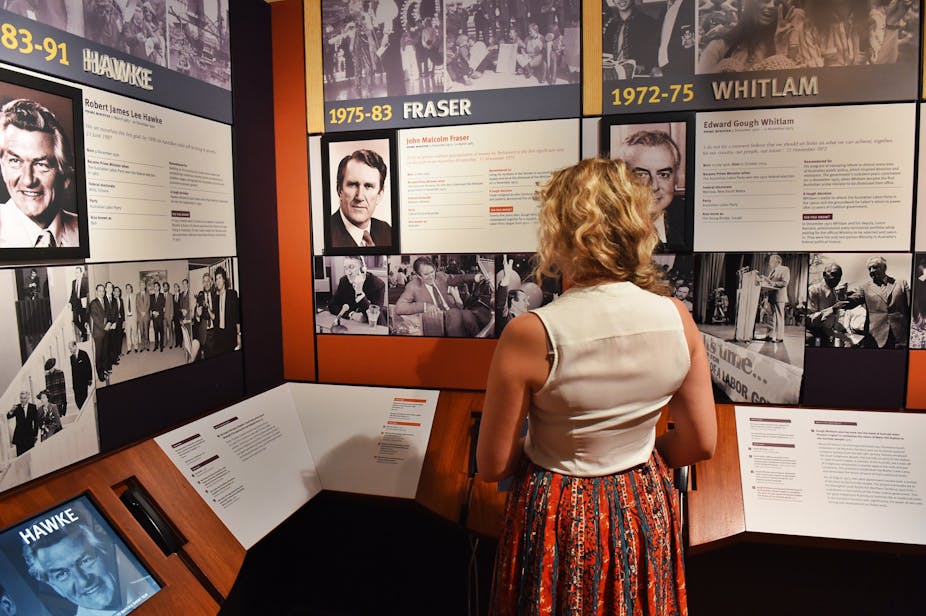

On what had begun as an unremarkable day, the news of the elected Whitlam government’s dismissal (which at the time we described as a “coup”) by the Governor General zapped through the school like an electric shock. What’s more, this foul deed had happened in cahoots, or so it seemed, with the then-Opposition Leader, Malcolm Fraser.

We were stunned and shocked, directing most of our anger towards those deemed to be the perpetrators, Fraser and Kerr. The latter was a Balmain boy, now branded as a “working class traitor”. Later, many young teachers and others like myself, sporting “Shame Fraser Shame” badges and T-shirts, went into the city to demonstrate in support of the sacked prime minister, The Hon. Gough Whitlam.

At the rally, Whitlam spoke brilliantly, oratorically urging us to “maintain the rage”. Our rage, we thought, could never end.

This morning, almost four decades later, on hearing of the death of Malcolm Fraser, I experienced comparable emotions. In feeling this way I am by no means alone in my generation. Why?

From this unpromising start, over time, Malcolm Fraser worked on and completed most of the work initiated by the Whitlam government, but which it was unable to implement properly. Fraser, derided at first as a “toff”, saw the passage though Parliament and implementation of the first Commonwealth Aboriginal Land Rights legislation in this country, the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act in 1976.

This returned vast tracts of “country” to Warlpiri people, with whom I would later work for many years on the collaborative project of implementing a successful bilingual program in Warlpiri and English. (Bilingual education was another Whitlam government initiative, which received continuing support from the Fraser government, although it was only ever very begrudgingly accepted by the Northern Territory Government).

Fraser also went on to champion multiculturalism. This encompassed taking a more liberal approach to immigration, including the acceptance of many Vietnamese refugees into Australia after the Vietnam War. In 1977 his government created a Consultative Committee on Ethnic Broadcasting, which eventually led to the establishment of the ethnic radio and television broadcaster, SBS.

In this regard, Fraser lent practical support to the twin ideals of multiculturalism and immigration, thereby promoting the acceptance of the ideal of a more inclusive Australia. Initiatives such as SBS enabled Indigenous and minority voices to circulate and be heard in the national sphere to a significantly greater extent than in the past.

Fraser’s approach to foreign policy was tough, but fair: he worked towards ending apartheid by applying sanctions to the Springbok rugby team in 1981, against a background of considerable public outrage at that time. In this, and his other words and deeds since then, Fraser led Australia out of what had been, in some respects, an ignoble past.

He also completed the project – again initiated by the Whitlam government – of dismantling the remaining vestiges of the White Australia Policy, the popular name given to the Immigration Restriction Policy of 1901, the first major piece of legislation passed by the newly-federated “Australia”.

Malcolm Fraser led not from behind, not by accepting the status quo ante of Australia’s lowest common denominator, but by actually providing real leadership in word and deed. In doing so, he took most Australians with him – at least, eventually.

This took guts. Moreover, well into his old age Fraser continued to speak up on difficult issues affecting us all. In spite of the backlash from many in his own party and from the Labor Party, whose ground some regarded him as usurping, his courage afforded him a unique form of greatness.

Over time, Malcolm Fraser gradually morphed, before our sometimes-suspicious, sometimes-astonished eyes, into Australia’s only true elder statesman, in many ways acting as the nation’s conscience. As one of the few remaining liberals in a putatively “Liberal” party, by holding certain core values dear, and refusing to depart from them, Malcolm Fraser filled a political vacuum.

Fraser defended and spoke up for the core Australian social and political values of a “fair go” for all. That void isn’t going to be easy to fill.