This week’s temporary suspension of comments on China’s two largest micro-blogging services Sina Weibo and Tencent Weibo highlight the ruling party’s discomfort with social media’s growing popularity.

Following the circulation of rumours regarding Bo Xilai’s downfall, government censorship has been swift and decisive with reports of up to six arrested and 16 websites closed

Despite reform and the Open Door policy adopted in China since 1978, a comprehensive mechanism of control and censorship on media, including the internet, continues.

There is no sign that anything close to a regime change is happening in China, but social media is beginning to play an interesting political role, sometimes influencing localised policy changes.

But these changes can only be accomplished with the government’s backing, and its tolerance of the informal cooperation between ordinary citizens and established leaders. In this small way, social media is helping authorities to become more aware of problems in the community and giving some citizens more opportunity to start public debate.

Making connections

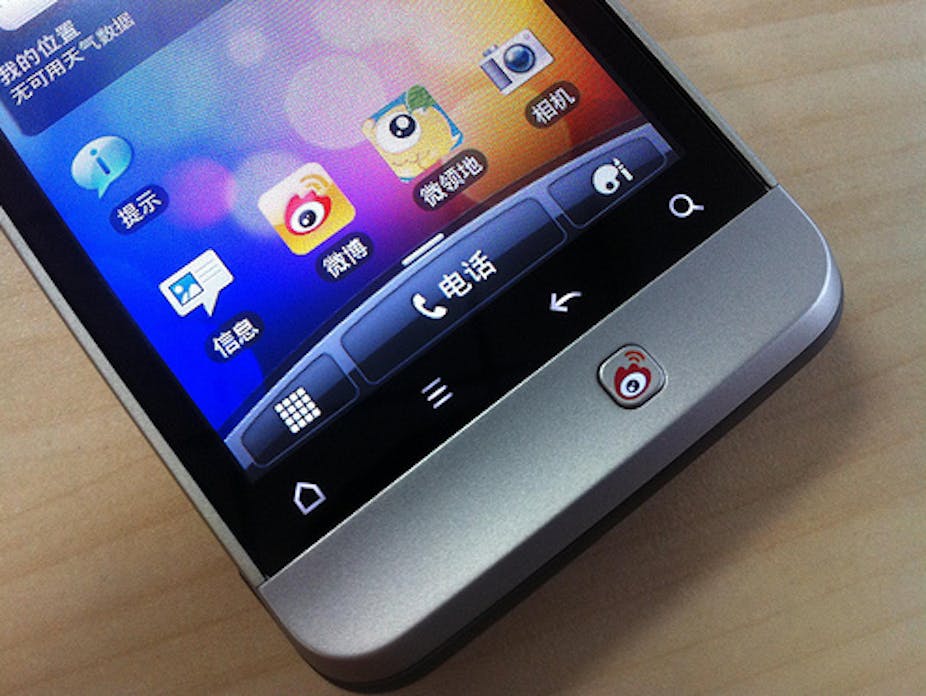

In the first half of last year, adoption of the Chinese microblogging site “Weibo” – a site similar to Twitter – jumped over 200% to reach 195 million or 40% of internet users in China. Since it took off last year, Weibo has featured in a series of high-profile events.

In July last year, a high-speed train crash in Whenzhou prompted many users of the site to vent anger about the crash and how it was handled.

Weibo also became a place for public outcry after the live broadcast of local officials harassing residents who appealed against the demolition of their houses. And on another occasion in reaction to a hit-and-run incident, where the driver boasted of his father’s position as a security official.

Help and hinder

In 2003, I studied the use of new media in China during an outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

As the epidemic began to spread in the Southern province of Guangdong, and information was unavailable from the news media (who were prohibited from reporting it) citizens sourced information from each other.

Between 8 to 10 February 2003, 126 million text messages were sent in the province, by a population of 79.5 million. A survey found that 80% of residents in the city of Shenzhen obtained news about SARS from text messages and the Internet.

But although mobile phones, emails and online bulletin boards enabled citizens to act as sources and publishers of news, they enabled the government to do the same.

This actually reinforced the government’s dominance as a source of news and also helped the government strengthen its control on citizen news.

Apart from human monitoring, keyword filtering was administered on internet bulletin boards. Undesirable citizen posts were deleted. Those who posted content were tracked, 39 of whom were later charged for spreading rumours and harmful information.

New technology, new censorship

During the SARS outbreak, Chinese citizens had the freedom to send text messages on mobiles unmonitored. But by June 2004, China adopted content filtering technology for mobile text messages.

In 2008, immediately after the Sichuan earthquake on May 12th, I studied the popular Tianya online bulletin board and the Sina video blogs.

A post on Tianya broke the news of the quake at 14:29 on the day, one minute after the tremor of 8 on Richter scale was recorded, ahead of any news report. The official Xinhuanet report didn’t file until 14:46, although it was more detailed.

In the initial days of the aftermath, citizen reports provided hyper-local description of damages in the epicentre, filling the information vacuum before news media reached the scene.

Blogger videos shot by citizens were shown by television news programmes, including on the official Central Television Station.

Citizen debates

On the whole, however, the amount of information provided by citizens was scant. But they did contribute by starting debates, which then set the agenda for the news media.

Questions were asked about whether the earthquake could have been forecast in advance, and whether the collapsed schools — being a major cause of deaths – were the result of shoddy construction.

By the end of May, a government official acknowledged that the collapse of some local schools was caused by a combination of factors in site selection, structural design, materials, and construction standards.

An investigation was launched by the central government, but so far it has refused to release the number or the names of the dead students.

Government infiltration

It has now become clear that people who publish on the online bulletin boards consist of laymen, experts and writers who could be commissioned to foster a positive image for the government.

On the Weibo platform, messages continue to be monitored, filtered and deleted. Government departments and individual officials are participating alongside laymen.

Institutional news media and celebrities are using the space to reinforce their positions. Social media platforms are a new space of contest, in which new alliances of power will be formed.