In our series, Better Teachers, we’ll explore how to improve teacher education in Australia. We’ll look at what the evidence says on a range of themes including how to raise the status of the profession and measure and improve teacher quality.

Top-performing international education systems value expert teaching and recognise that highly effective teaching improves student outcomes.

While there are some reforms in development, further work is required in Australia to lift the quality of teaching by attracting the brightest candidates into the profession and ensuring they receive the best preparation and ongoing support.

The federal government’s new requirement for teacher education students to be in the top 30% for literacy and numeracy is important. However, an effective teacher has more attributes that this.

Of the almost 4,000 teaching students who undertook the literacy and numeracy test in May-June this year, 95.4% met the literacy standard and 93.1% met the numeracy standard. So this measure’s impact is minimal.

This was only one recommendation of the Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG). There are 38 others still in the process of being implemented.

With key recommendations around tougher accreditation standards, TEMAG’s framework challenges initial teacher education providers to develop high-quality programs that can be rigorously assessed.

Universities will need to be able to demonstrate the positive impact they have on their graduates and that their graduates have on student learning. The latter is the mark of effective teaching.

TEMAG’s recommendations are not window-dressing. A paradigm shift, deep program reform and university support will be required to tackle current problems in teaching quality.

Too many teachers

Poor workforce planning by governments is further exacerbating concerns about teaching quality in Australia: supply is not well matched to demand.

The uncapping of undergraduate places in 2012 led some universities to exploit the fact that they receive funding for as many students as they can enrol. This has been a factor in the oversupply, giving the impression universities use teaching courses as a “cash cow”.

The largest education department, New South Wales, hired just 6% of the state’s graduates on full-time contracts last year. Education Minister Adrian Piccoli made the point that universities:

… have doubled entrants in the last ten years … They should take fewer and do a better job [of training them].

By investing wisely in the best evidence-based teacher education programs, the federal government can foster quality teaching without increasing total funding. This would also overcome the ethical issue of preparing teachers who have little chance of being employed.

Undersupply of specialist teachers

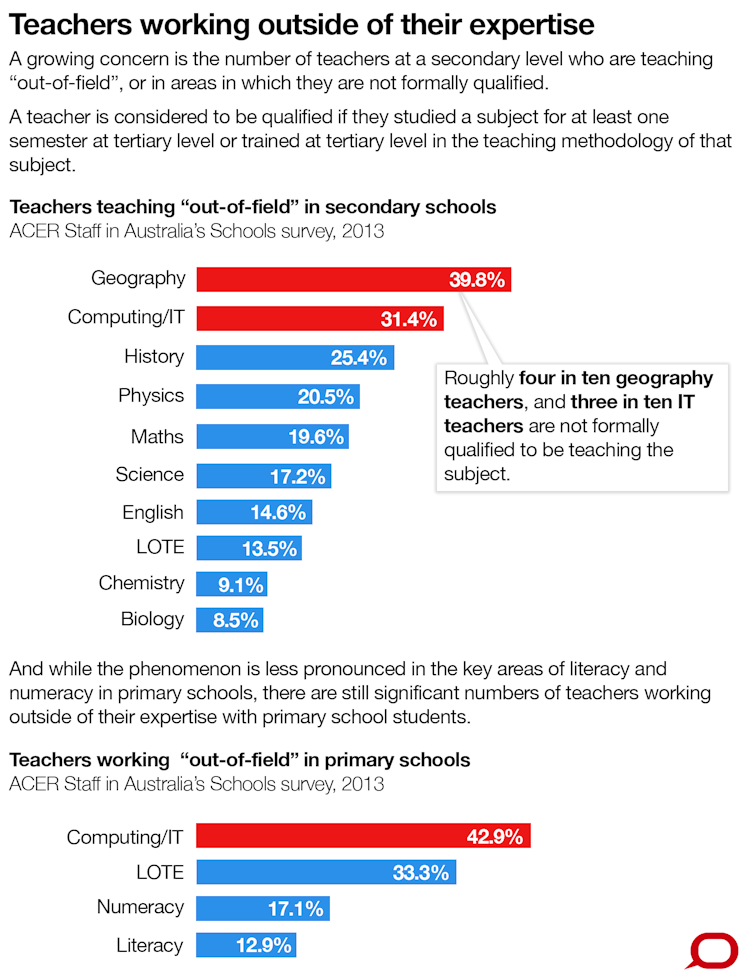

Despite general oversupply, Australia is experiencing a significant undersupply of language, geography, computing and history teachers, as well as secondary maths, physics and chemistry teachers, and qualified teachers in some regional areas.

As a result, more than 20% of secondary mathematics and 17% of secondary science teachers are unqualified in their field. Without even year 12 training in these fields, many science and maths teachers lack the ability to spark enthusiasm for these subjects in their students. This is why TEMAG recommended the introduction of specialist maths and science primary teachers.

Undervalued profession

To attract the highest-quality entrants, we also need to hold teachers in high esteem.

Teaching is arguably the most challenging profession of all, yet unlike Finland – where teachers accrue similar respect to doctors – we don’t recognise that teaching deserves the same respect and trust as the medical profession. Finland also demands graduate teaching qualifications.

Graduate students bring real-world experience, including deep disciplinary knowledge, analytical thinking and personal maturity. These are more powerful attributes for selection than the year 12 Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR).

The Victorian government flagged the prospect of graduate-only entry into teaching courses in a recently released discussion paper.

This would follow in the footsteps of the South Australia government, which intends to require all teachers to have completed a graduate-level teaching degree. The state will also require government schools to preference the employment of graduates with master’s or double-degree teaching qualifications.

To attract the best candidates, prospective teachers need to see a career progression. Using the current lead teacher and accomplished teacher categories but linked with an appropriate pay level progression would be a good start.

Teachers have a crucial role in improving student outcomes. We need not only to lift course and graduate standards, but also to ensure teachers are well supported so they can contribute fully as highly developed experts in a widely respected profession.

• Read more articles in the series