One of the great legacies of the development of cultural studies in the 1960s has been the academic acceptance of seriously analysing everyday things. We engage with these things to reveal unseen tensions – political, ideological and social – that can then be mapped against what cultural arbiters generally deem more significant.

For example, in Our Aesthetic Categories Sianne Ngai brilliantly analyses Lucille Ball’s zany performances as staging our anxieties about the confusion of work and play in a post-Fordist service economy. And I’ve looked at how listing as a comedic trope in the Lego movies suggests the death of the critical potential of irony in a networked age.

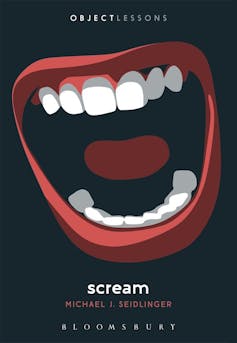

The point of this kind of critique is to make the everyday strange, to reveal the ideological forces that sustain its function. With titles like Doll, Stroller, Refrigerator and Driver’s License, this is the idea underpinning the Object Lessons series from Bloomsbury: short books (each around 25,000 words) about “the hidden lives of ordinary things”.

Review: Scream – Michael J. Seidlinger (Bloomsbury)

How seriously we take the work may depend on our own predilections – as with many of cultural studies’ objects of analysis. But it’s always been something of an axiom that if you’re writing about something most people would deem trivial – dismissing your work with that most idiotic of anti-intellectual phrases, “overthinking it” – then your work has to be of an exceptional standard. To avoid likely ridicule, one’s scholarship and writing must be magisterial.

It was with this in mind that I eagerly opened Michael J. Seidlinger’s recent book in the Bloomsbury series, Scream. A cultural history of screaming throughout horror cinema, heavy metal, art, social life? Now that’s a neat conceit for a book.

Alas, Scream falls far short of its promise at the level of breadth and depth of analysis. And, even more noticeably, in terms of the quality of the writing itself.

I scream, therefore I am

Scream’s very existence suggests, perhaps, that cultural studies-style approaches have become so popular across social media (and in internet culture more broadly) that the requirements for rigorous analysis and precise expression have abated.

Seidlinger’s text is often pitched in the lexicon of self-affirmation, echoing online victim culture: “I scream therefore I am”.

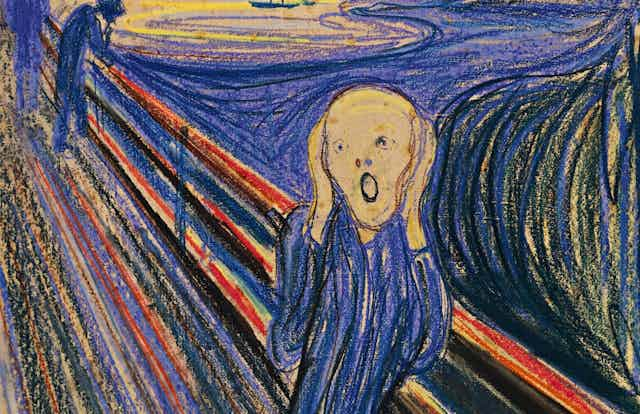

It oscillates between a discussion of significant cultural artefacts involving screaming – Munch’s era-defining painting, for example, and Wes Craven’s slasher film of 1996 – and personal reflections. These cover growing up, feeling awkward, and turning to screaming media (mainly horror cinema and nu-metal) as a way of trying to deal with that.

A handful of interesting topics are visited. The annual “Grito de Dolores” festival, for example, which celebrates the start of the Mexican War of Independence. The parish priest of Dolores Parish Church, in Guanajuato, Mexico, kicked off the Mexican War of Independence in 1810 with his rallying battle cry – the “cry of Dolores”. Every year, the Mexican president re-enacts the cry, while ringing Hidalgo’s bell. Seidlinger describes the Austin, Texas version of the event, celebrated annually.

Or Ashley Peldon, Hollywood voice actor and screamer extraordinaire, who has opened up her lungs in numerous films and videogames. But, at every point, Seidlinger reduces the significance of these subjects to their dullest form, mining every topic to produce its most banal possible message.

Take Munch’s The Scream, for example. That masterpiece exemplifying the existential crisis of modernity – what’s the point of screaming when you have no ears? – is reduced to the most blunt platitudes about human nature and the need for connection. It is:

one of our most essential displays of a prevailing human condition […] It’s no wonder The Scream became so fascinating and popular: We all feel this way, more often than not, pressures flanking us through thick and thin.

Munch’s masterpiece becomes simply the product of an angsty artist expressing himself through painting (rather than a tweet?). Decades of art historical analysis are reduced to insignificance by Seidlinger in his revelation of the eternal truth of great art: it’s a cry for help from artists (like himself, Seidlinger is quick to point out).

Even the discussion of screaming in metal is far from comprehensive. Seidlinger fails to mention some of the key nodes in its history. Norwegian black metal, for instance. Or – a weird oversight, given the global megastardom of the band – Phil Anselmo’s legendary melodic screaming in Pantera.

Seidlinger seems to focus only on stuff he knows and likes. And this is okay for some kinds of writing, but it doesn’t legitimise or sustain the broader anthropological, historical or cultural points Seidlinger is trying to make.

At the same time, there are factual mistakes throughout the work. He refers to John Carpenter’s Halloween, for example, as being from 1976 – when it’s from 1978. While these mistakes are not major in and of themselves, they draw attention to the dilettantish nature of the project as a whole.

Read more: Why ‘The Scream’ has gone viral again

Low-stakes victimhood

Indeed, the book belies its promise of culturally analysing screams. Instead, it’s mainly a kind of confessional exercise by Seidlinger, as he interminably riffs on his screaming attempts to overcome the traumas of his youth. These have led, he explains to us numerous times (ten maybe?), to him having panic attacks. (How many times can you mention you have panic attacks in a 25,000-word book?)

The problem is, the stakes of his victimhood are remarkably low. A major trauma, for example, is the fact his mother made him stay at the table until he’d eaten his food. Almost a whole chapter is dedicated to the aftermath of an incident when a high-school friend stopped liking him because Seidlinger failed to stand up for him when he was being bullied.

The point? These terrible crises – what could be more PTSD-inducing than having to eat food off your plate? – have been causing Seidlinger to scream throughout his life, apparently. And their recounting here caused me to scream, with a mixture of irritation and boredom.

One cannot doubt Seidlinger’s earnestness. But how or why a petty high-school confession would be deemed interesting enough to be published by the academic arm of a quality publisher is baffling. The incident reads – and this is no exaggeration – like the kind of self-pitying Facebook post one might come across from an old school friend that makes one cringe for a minute, before it is happily forgotten.

Seidlinger too often approaches the scream through this kind of personal optic. Again, it’s a neat idea for a book – but his understanding of people is both incredibly generic and overly personal.

His perspective is shaped by a kind of pop-psychology and self-help American discourse, one that uncritically affirms the therapeutic nature of self-expression and its public benefit – regardless of artistry or aesthetic merit. And it’s derived from personal experiences, projected onto the species as a whole.

Seidlinger frequently speaks about “our” anxiety and fears in an anthropological register, when really he’s just describing his very specific (and surely not shared by many) experiences.

Lonely perhaps, but we all are, at our core, saddened by the reality that we’re alone in facing our demons, our challenges.

I suppose one could suggest there’s something courageous in Seidlinger’s candour. But really, this should be judged on the basis of its contribution to public discourse. And I can unequivocally state that knowing this author is angry at his mother – because he thinks she was mean to him when he was three – makes no contribution to public discourse.

At the same time, the very sites of the author’s courage are actually predictably safe. They’re the kind of stuff people use to mine “likes” on social media – relying on the popular trope of the heroic, traumatised victim speaking out.

Read more: Friday essay: in praise of the 'horror master' Stephen King

Howlers and nonsense

But where this book really excels is in how monumentally bad the writing is. At times I felt like I had woken up in an episode of The Twilight Zone, given Bloomsbury’s excellent track record.

The prose is irredeemably littered with clichés (far too many to mention). Clichés may economically introduce a particular idea or mood. They can be useful in popular writing as blunt and inexact instruments, for this very reason. But they have no place in serious cultural analysis.

Aside from obvious howlers, such as where he refers to The Scream as “the famous painting that everyone knows about”, the prose is full of passages that at times border on nonsense.

We can write what we feel without expressing it physically. I’m doing that right now. Yet we fail to remember that even the most powerful physical registers of human expression, like the scream, can become purely invisible, funneled through technology and the internet. It can become metaphorical, stripped of its trademark bold first impression.

And:

The severity of our emotional condition after losing someone – there is rarely a more saddening feeling. Those found at the crossroads of loss can feel dejected as much as they feel enlightened. The elements thought to be invisible and imaginary are suddenly made visible.

And, my favourite: “The emergence of human scream analysis has lifted the veil of mystery surrounding our preternatural allure.”

The imprecision of the expression is equally notable. As one example (among several), he writes: “A young 27-year-old sits at his desk.” But does this mean a young person who is 27? (Young according to whom?) Or someone who has just turned 27, as in: is closer to 27 than 28? It’s plain weird to read.

Much of the book is written in sentence fragments, turning to (and depending on) the insular appeal of the internal monologue as a way of masking an absolute lack of command of the material (and medium). This isn’t, strictly speaking, an academic text – so some lack of rigour can be forgiven. But the writing falls well below the standard of, say, an article in a popular newspaper or magazine.

Oscillating between cultural analysis and personal anecdote, it’s hard to understand who the imagined reader for this book may be (other than Michael J. Seidlinger, who I suspect would enjoy it).

It’s neither insightful nor comprehensive enough to be of value to the critical theorist or cultural studies scholar. And I can’t imagine it would be of much interest to a popular readership.

Scream certainly has a good premise. But it fails completely as a book. The writing is so bad and the argument is too dependent upon a not particularly enlightening point – a truism really: screams are attempts to connect with other humans, and they can be both positive and negative.

The prose tries to be lively, but it feels lightweight and repetitive – personal in an attempt to cover up its lack of substance. Yes, screams ambiguously suggest both torment and vital intensity. So what do my screams while reading this book suggest?