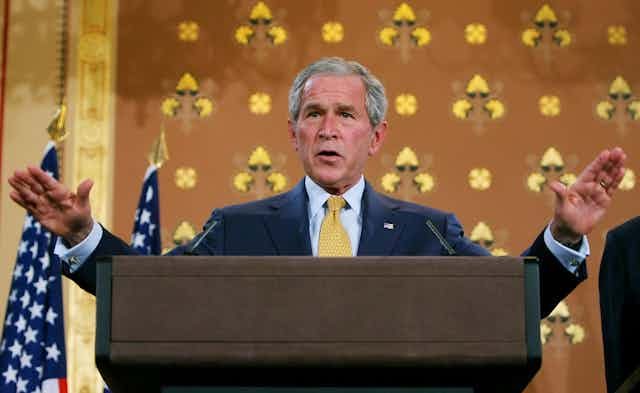

Be under no illusion, the world is losing the fight against climate change. The amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere continues to increase, meaning humanity is forcing the Earth closer to cataclysmic alterations that will reshape the entire biosphere. But the UK could capitalise on the momentum gained through its recent net zero emissions pledge to take the lead and herald a shift towards serious global climate action. How? By copying a strategy followed by – of all people – the George W Bush-era neoconservatives.

Hear me out. Those who disagree with my opening statement will of course point to the Paris Agreement: a global alliance that boasts 185 signatories fighting back against climate change. Yet Paris is a reflection of international law, which means it represents only the lowest common denominator that those negotiating parties could agree. For this reason the agreement is premised on state discretion, taking the form of “nationally determined contributions” where countries decide for themselves how much they will cut their emissions.

The agreement does have positive attributes, and there is scope to argue that it is useful. But it is not able to compel states to hit the ambitious targets necessary to stave off the threat of more warming. Climate Tracker illustrates this by finding that five states are “critically insufficient” in their efforts to prevent more than a 1.5°C increase, and a further 19 states are at least “insufficient”.

Beyond the Paris Agreement?

Countries could instead deal with contentious international threats by stepping away from the usual processes of international law, and introducing frameworks that aim to uncompromisingly challenge the root of the menace. And there is some precedent. One example is the 2003 Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) – a set of principles designed predominantly by the US to curb the international transfer of materials related to nuclear weapons.

Crucially the PSI was not negotiated. Instead states were invited to endorse a framework of principles that had already been created. The argument was that a typical treaty would be too slow, too cumbersome, and reflect the usual challenges of international law, ruling out any serious responses.

The PSI was able to attract 11 countries at its inception, and currently 107 countries have endorsed its principles. Its success is measured by the fact it is still in operation today and is considered to have increased cooperation and indeed reduced the transfer of nuclear weapon material.

The context was of course 9/11, which drove the US and its allies to pursue aggressive international policy absent any meaningful reflection on what those policies would mean for the multilateral landscape. Among the neocons who partly ran Bush’s foreign policy, the prevailing mood was that extreme times call for extreme measures against a threat they could not easily grasp. Sound familiar?

There is a certain irony in linking the PSI to climate change, as the same Bush administration was actively against a robust climate policy. Yet though it lacks in international diplomacy, the same strategy offers clear practical advantages.

The PSI was only possible because the US was determined that the threat of nuclear weapons was so severe that it had to lead on a response. This is precisely the type of leadership that is lacking on climate change.

A role for the UK?

There have been some positives in 2018, and the UK has emerged as a potential climate leader. Following the paralysis of London by activist group Extinction Rebellion, the UK parliament took the unprecedented step of declaring a climate emergency, though what this means precisely remains unclear. Then there was the announcement of legislation to target net zero emissions by 2050 by the outgoing prime minister, Theresa May.

So how to capitalise on that momentum, and spread it worldwide? My suggestion is that the UK follow the precedent of the PSI and create a Climate Security Initiative (CSI). A CSI could encompass a set of bold principles to reduce emissions and champion green technology, going well beyond the Paris Agreement and propelling the UK into a leadership position that other like-minded states would be able to support.

There already exist a number of states that could form an initial CSI group, all willing to commit to radical steps to fight climate change. Ireland, for instance, has also declared a climate emergency. New Zealand, too, has begun the legislative process to become carbon neutral by 2050, while Finland has targeted 2035.

Of course the proliferation threat does differ from climate change. The latter is intrinsically linked to the global economy and the behaviour of billions of people. Decarbonising humanity will mean radical change on an unprecedented scale, spanning from the state to the individual. Yet we can choose to control this change through net zero aspirations, or we can have it forced on us through a radially altered climate not necessarily conducive to human existence.

The benefit of a CSI approach is that not only can it be designed to meet the threat head on, something the Paris Agreement has failed to do, but also if led by the UK it will help to counteract the narrative that the developed world simply isn’t doing enough to combat its historic role in emissions creation. A CSI offers the UK a way to transfer its recent political declarations into tangible action, without being stifled by international law.

If the UK really wants to “lead the world to a cleaner, greener form of growth” it has to look beyond the Paris Agreement, and beyond its own borders – something a Climate Security Initiative could achieve.