It was no April fool’s joke when the Rockefeller Foundation announced it will phase out funding for the 100 Resilient Cities network. The foundation’s message was a surprise for many participating cities, including Melbourne and Sydney, and for its partnering non-governmental organisations, businesses and academics.

100 Resilient Cities is a global network designed to increase urban resilience, defined as:

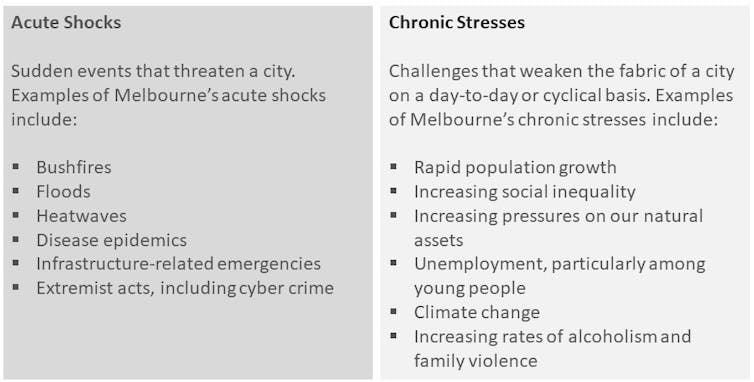

the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses, and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience.

Read more: Pacific island cities call for a rethink of climate resilience for the most vulnerable

Since 2013, the Rockefeller Foundation has invested more than US$150 million in 100 Resilient Cities to support cities in tackling environmental, social and economic challenges.

Each city receives funding for a chief resilience officer, a position located in councils to lead the city’s resilience efforts, and for drafting a resilience strategy. Member cities also gain access to knowledge and expertise through a network of partners from private, public and non-governmental sectors.

Where are these resilient cities?

The network has grown to 97 cities, including cities from the Global North and South. Prominent members include New York City, Rio de Janeiro, Singapore and London. In Australia, Melbourne and Sydney were among the first two groups of cities that joined in 2013 and 2014 respectively.

Even though the growing number of member cities is a success, representatives of 100 Resilient Cities made clear that the “task is far from complete”. Almost half (47) of the 97 cities are still developing their resilience strategies.

When the program stops in July, it is unclear what will happen to the knowledge gained through city strategy processes, the many positions created in local governments to support the program, and thousands of resilience actions started by cities under this banner.

How has Melbourne benefited?

Melbourne joined on the agreement that it would include all 32 of its metropolitan councils to challenge the divide between inner and outer urban areas.

Read more: Rapid growth is widening Melbourne's social and economic divide

In 2016, Resilient Melbourne released Australia’s first resilience strategy. It identified shocks and stresses, and outlined strategies in fields such as urban greening, emergency management, transport, housing, social inequality and energy.

One of these is Living Melbourne: our metropolitan urban forest, a newly released strategy to increase vegetation cover in the city. This action links and extends existing urban greening initiatives. The core goals are: increased biodiversity; better air, soil and water quality; heat reduction; and improved physical and mental health.

Read more: How Melbourne's west was greened

The Nature Conservancy, a non-profit environmental organisation and partner of 100 Resilient Cities, helps to develop this action, particularly with technical expertise.

Living Melbourne showcases how to bring together stakeholders from all levels of government, business, civil society and academia. Our research project found many stakeholders see Resilient Melbourne as a new platform for knowledge exchange and urban innovation.

These findings resonate with an Urban Institute study on the early achievements of 100 Resilient Cities. The study found many cities, after joining the network, show a stronger interest in collaboration across government agencies and between public and private sectors.

It also found ongoing challenges, including a lack of transparency and community participation. These aspects need closer attention in future resilience-building initiatives and city networks.

Read more: Has the 100 Resilient Cities Challenge benefited Melbourne?

What now?

Actions such as Living Melbourne are the result of collaboration and learning processes within and between cities. It shows that resilience actions must be implemented as ongoing and inclusive experiments that test new ways of urban development.

However, it is too early to review the success of the initiative in total. This applies particularly to the impacts of actions aimed at driving institutional and social change that might only become visible in 10 or 20 years.

The immediate value of these networked efforts, as Resilient Melbourne has proven, is to connect local experiences to international agendas, learn from other cities’ experiences, and access technical and financial inputs. They also support new conversations that involve “communities of practice” across the whole city, linking citizens, resilience practitioners, experts and businesses.

Yet the change of heart at Rockefeller and the relatively sudden shift in support illustrates a very tangible risk of privately funded philanthropic support for international initiatives on cities.

One solution is to diversify the funding mixes at the heart of these networks. Another global city network, C40 Cities, has pursued this in recent years.

Another solution is to allocate greater responsibility for cooperation across national, state and local governments. This should help with longevity, transparency and policy learning in city networks. The Swedish national Viable Cities program provides a model of this.

In the wake of these experiences, a more open and strategic conversation on the role of philanthropy in advancing urban resilience agendas should take place urgently.