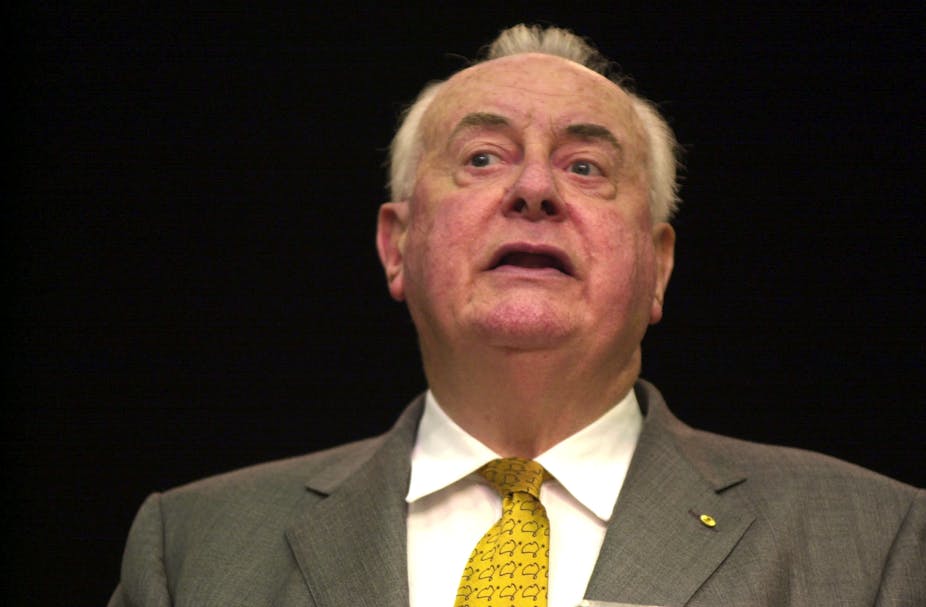

Former prime minister Gough Whitlam, whose death at age 98 was announced on Tuesday, left significant legacies from his short time in office. Whatever their condition today, many of his government’s initiatives, including free tertiary education, will long be remembered. Yet there is another legacy that is largely overlooked: the Commonwealth Commission of Inquiry into Poverty.

Whitlam advocated for this inquiry for years before then-prime minister William McMahon finally agreed in August 1972. In doing so, McMahon instituted an impressive political backflip in the face of a looming election.

McMahon lost the election and Whitlam moved quickly to expand the scope of the inquiry. He appointed four new commissioners to join the existing commission chair, Professor Ronald Henderson. They were to investigate specific aspects of the scourge of poverty affecting increasing numbers of Australians, including race, education, health and law.

Henderson had conducted an earlier study of poverty in Melbourne, during which he had set a poverty “line”. Essentially, the line was a measure by which we could tell who was and who was not experiencing poverty in our society. The inquiry is best remembered for refining and popularising that line, however contentious its usage is today.

But the inquiry did more than consolidate a poverty line. It commissioned 34 research studies and two national surveys. It attracted more than 400 written submissions. Some 180 of those submissions were followed up through public and private hearings around Australia.

“Poverty is not an academic question,” Whitlam had argued in one of his many attempts to get such an inquiry up. “It’s a moral question.”

In answering this moral question, Henderson made two major departures from Australia’s traditional approach to thinking about the poor. The first was that he blamed not the individual, but the structures of our social order.

The second: he listened to the poor.

Others had made such attempts in the years leading up to the inquiry, but never had they done so as publicly, nor with such endorsement from the federal government.

Henderson made his approach clear in the introduction of his first main report. He wrote:

Poverty is not just a personal attribute: it arises out of the organisation of society.

To be a woman, to be single, to be Indigenous, to be old, to be born overseas, to have a large family: these attributes alone could mean a person was poor. Being poor also meant being humiliated. Henderson quoted from a Tasmanian Council for the Single Mother and Child submission to make this point.

When first making application for an allowance the single mother rapidly discovers that if she is ever to get to the point of seeing a welfare officer she must relinquish any ideas of pride, dignity and the right to personal privacy.

The council was one of many organisations that spoke on behalf of the poor. The words of the poor were not always filtered, however: at times individuals spoke directly to the commissioners.

Many of those records are kept today in the University of Melbourne Archives. To date and to our detriment, they remain largely untouched. Sifting through them, I was struck by the enthusiasm of one Aboriginal man, who seemed pleased to have finally been asked what he thought. His two-page submission began:

Being affected by personal and cultural deprivation I have not been able before this to respond to the challenge and oppornunity [sic] to speak for the poor people and Aboriginal people of this country.

It is testament to a level of generosity of spirit that he was prepared to contribute to a system that had treated him so badly and ignored him for so long.

At the centre of the inquiry’s final recommendations was a guaranteed minimum income scheme. Such a scheme, Henderson argued, would place “a minimum disposable income … as one of the rights of Australian citizenship”.

Under this system, Henderson continued, there would be:

… no longer any hierarchy of deserving and undeserving poor, categorised according to administratively awkward tests, with all those unfortunates at the very bottom of the hierarchy not entitled to any income at all.

Henderson’s report was presented to Whitlam in April 1975. In the face of economic decline and other political pressures, the minimum income proposal proved a progressive step too far even for Whitlam, at least in the short term.

That November, Whitlam was dismissed.

While Whitlam was not in power when the inquiry was announced, he drove its introduction. In expanding its focus and allowing it to run the length of his time in office, he made possible a new and kinder consideration of the problem of poverty in Australia.

That inquiry left Australians with a poverty line that provided a way of – at least to some extent – gauging the level of poverty in our communities. That line continues to be updated today.

It left Australia also with plans for a minimum income scheme. While doomed, they represented a climate of real optimism, when structural reform to alleviate poverty appeared a real possibility.

Perhaps most importantly, though, the inquiry heralded a new way forward in terms of listening to the poor.

Revisiting the records of that inquiry means hearing from many ordinary Australians who, often for the very first time, found a voice in the national debate on a topic; who told of the realities of poverty as it applied to their world. This legacy of Whitlam’s – while often overlooked - is one worth revisiting.

Editor’s note: Fiona will be on hand for an Author Q&A session between 9:30 and 10:20am today (October 23). Post any questions about Whitlam’s inquiry into poverty and its legacy in the comments below.