Last week negotiations to ban nuclear weapons started in New York. The talks came as a result of United Nations General Assembly resolution adopted in December last year.

The resolution takes forward multilateral negotiations on complete nuclear disarmament.

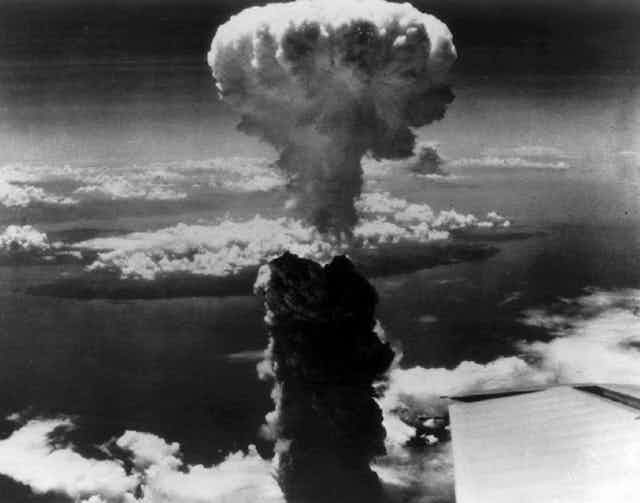

States started negotiations on nuclear disarmament in 1946, a year after the atom bombs were dropped on Japan. But the talks faltered as the Cold War warmed up.

Fearing that the spread of nuclear weapons would make those states that had them even more reluctant to give them up, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons was negotiated and entered into force in 1970.

The treaty was the first building bloc on the road to a world without nuclear weapons. It prevented states that didn’t have nuclear weapons before 1968 from acquiring them. And it prohibited states that had nuclear weapons from providing other states with them.

The non-proliferation obligation of the treaty has been exceptionally successful. Nuclear weapons have spread to only four other states since its inception. Today there are nine states with nuclear weapons: the original five, namely the US, Russia, the UK, France and China. The other nuclear armed states are India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea. They are not members of the nonproliferation treaty.

The non-proliferation obligation of the treaty should be seen in the context of Article VI of that treaty, requiring all its members – including the five original nuclear weapon states – to negotiate in good faith general and complete disarmament of nuclear weapons, in other words, to negotiate a world without nuclear weapons.

This is the disarmament obligation of the treaty. Unfortunately, it stated no deadline for these negotiations. This legal loophole has been used by the nuclear weapon states to delay giving up their arsenals.

In fact, the treaty is disingenuously interpreted to suggest that the five original nuclear weapon states should be allowed to have these weapons, but not any other states. India has referred to this situation as “nuclear apartheid” and therefore refused to join the treaty.

For the first decade and a half after the treaty entered into force, the number and size of nuclear weapons in the arsenals, particularly the US’s and Russia’s, spiked to irrational levels. In the event of a nuclear war they could destroy the world several times over

The end of the Cold War saw a decline in nuclear weapons, but there are still an estimated 15 000 around and, worryingly, plans to modernise them.

As a co-sponsor of the resolution, South Africa is playing a key role in the negotiations. The country holds the moral high ground because it was the only country to voluntarily give up its nuclear weapons.

The Nuclear Ban Treaty

Since 2010 states, civil society and individuals working for nuclear abolition engaged in what has come to be labelled the humanitarian initiative. This aims to shift the focus from which states are “responsible” enough to have nuclear weapons to the fact that nuclear weapons are inhumane and illegitimate no matter who has them.

The International Committee of the Red Cross has been outspoken about the unspeakable suffering and destruction that a nuclear detonation by intent or accident would have.

Because nuclear fallout and radiation cannot be contained within the borders of a country, or for that matter a generation, nuclear disarmament is a matter for humanity at large.

Several precedents for banning inhumane weapons already exist, such as conventions banning chemical and biological weapons as well as the antipersonnel mine ban treaty.

For these reasons 113 states voted for the UN resolution to negotiate a nuclear weapons ban last December. Some observers are worried about the fact that 35 states voted against the resolution and 13 abstained. Although 130 states joined the talks, more than 40 states, including those with nuclear weapons, are boycotting the negotiations.

Important first step

Some fear the boycott will mean that the ban treaty is a nonstarter.

But the ban treaty should be seen as an interim step to global denuclearisation. It’s the second building block towards a world free of nuclear weapons.

It will create the political space to stigmatise nuclear weapons. Those who have them will come to feel increasingly isolated and on the wrong side of morality.

The aim of the ban treaty shouldn’t be to force nuclear armed states to give up their nuclear weapons. Rather, it should be to create an atmosphere in which they themselves understand that there’s no prestige, security or power in having these weapons.

Moreover, the ban will strengthen the so-called nuclear taboo that’s kept states from using nuclear weapons since 1945.

As an interim step, the nuclear ban treaty need not be a complicated legal document outlining the technicalities of, for example, verification measures.

For now the nonproliferation treaty provides a sufficient foundation for the nuclear ban treaty to draw on. The technical work would be the job of the third building bloc, a convention on the complete elimination of nuclear weapons. This would be negotiated with the nuclear armed states on board.

South Africa’s activist position

South Africa joined the nonproliferation treaty late. Given its international isolation under apartheid, it developed nuclear weapons to blackmail western states to come to the regime’s rescue in case of an attack by the Soviet Union, which supported the armed struggle against apartheid.

Towards the closing years of apartheid, President FW de Klerk decided to dismantle South Africa’s nuclear weapons. Some observers argue that this was a racist move to ensure that nuclear weapons weren’t left in the hands of a black government. But the African National Congress came into power with a longstanding policy against nuclear weapons, intent on using nuclear power for peaceful purposes only.

This policy was informed by an African and Non-Aligned Movement perspective . South Africa therefore holds a special place in the nuclear order because it was the first state to voluntarily give up nuclear weapons.

The country’s nuclear diplomats built on this moral high ground and have worked tirelessly for nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament since 1994, while ensuring access to peaceful nuclear technology.

The fact that the ban treaty negotiations are taking place despite opposition from the permanent members of the UN Security Council may even suggest a democratic turn in UN politics. South Africa is working with like minded states and civil society on the front line to make this next step toward a world without nuclear weapons a reality.