Australia just became the odd one out.

At its meeting last week, the US Federal Reserve kept its official interest rate on hold. A week earlier, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Canada kept their rates on hold, and, at their meetings before that, the Bank of England and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand did the same thing.

Throughout the Western world – with perhaps Australia as the only exception – financial markets have been assuming central banks were done with increasing rates and would soon start pushing them down.

Reserve Bank Governor Michele Bullock’s statement accompanying Tuesday’s hike in Australia’s cash rate makes it look as if we’re about to join that club. It makes it look as if this hike from 4.1% to 4.35% – a 12-year high – will be the last.

And with good reason. Inflation has been falling almost everywhere, and – notwithstanding the recent uptick associated with higher oil prices – is forecast by the International Monetary Fund to keep falling.

The RBA has taken out insurance

So why did Australia’s Reserve Bank push up rates at all, at a time when none of its global peers were?

The statement makes it look as if it wanted to take out insurance.

While the bank still expects inflation to continue to fall, it says progress now looks “slower than earlier expected”.

Its revised set of forecasts, to be released on Friday, still have inflation falling, but to around 3.5% by the end of next year, instead of 3.3%, then to around 3% by the end of 2025 instead of 2.8%.

The bank is particularly worried that the prices of services – things such as service in a cafe, done by hard-to-find workers – are “continuing to rise briskly”.

And it mentions “uncertainties” four times in eight paragraphs. It isn’t that it thinks inflation won’t keep coming down; it’s that it wants to be sure it is.

Australian hikes hit harder than in the US

One argument the bank hasn’t used – and nor should it – is catch-up. The US, the UK, the EU, Canada and New Zealand all have higher official rates than Australia.

But they are all are different to Australia, in an important way.

When the US Federal Reserve pushes up its Federal Funds Rate, nothing much happens to US home borrowers. Here’s why: almost all US home borrowers are on fixed rates, meaning their required mortgage payments don’t increase.

In Australia, only about one-third of home loans are fixed.

And US fixed rates are nothing like Australian fixed rates. The typical term in the US is 30 years, rather than the two to three years common in Australia.

This means that, as long as borrowers in the US don’t refinance or move homes, their payments are fixed for the entire term of their loans. Americans never have to pay more just because the Fed jacks up rates.

At least when it comes to homebuyers, the US Fed has to do a good deal more than Australia’s Reserve Bank to have the same effect.

It means the US official rate of 5.25% has less immediate effect on ordinary Americans than Australia’s new rate of 4.35% will have on us.

That’s what the consumer spending figures show.

After a year of high US rates, American consumers are buying 2.9% more goods and services than they were a year ago.

After a year of less-high Australian rates, Australian consumers are buying 1.7% less.

This means that, as relatively lightweight as our previous 4.1% cash rate had seemed, it might have been packing more punch than the higher 5.25% rate in the US; and also the higher rates in the UK, Canada and New Zealand, where most of the mortgages are also fixed.

‘Painful squeeze’

In her statement, Governor Bullock acknowledged many households were experiencing “a painful squeeze on their finances”. She also noted others were benefiting from rising housing prices, substantial savings buffers and higher interest income.

Bank calculations suggest one in 20 variable-rate borrowers are now going backwards – paying more for essential expenses and housing than they earn.

Among borrowers with big loans relative to their incomes, it’s one in four.

There’s nothing in the governor’s statement to suggest she is thinking of pushing up rates again. After today’s hike, the futures market assigned only a 30% probability to another hike.

The best guess of people who bet on this for a living is that Australia is about to join the rest of the world and leave rates where they are for quite some time.

A frugal Christmas, before possible rate drops in 2024

Alternatively, rates could even begin coming down within 12 months.

The detail of the inflation figures shows monthly inflation surged to 0.8% for one month only, in August, when petrol and diesel prices jumped 9.1%, then fell back to 0.3% in September, which is where it was before petrol prices jumped.

It is also looking like prices scarcely increased at all last month.

The Melbourne Institute inflation gauge, which comes out ahead of the Bureau of Statistics gauge and broadly tracks it, fell 0.1% in October. This suggests that, when taken together, price falls (slightly more than) outweighed price increases.

It’s what you would expect if we were tightening our belts, as we are.

At Big W discount department stories across Australia, sales are down 5.5% on where they were a year ago.

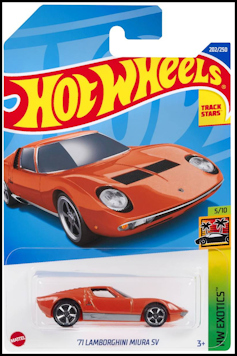

Big W says shoppers have moved away from buying big-ticket items and are instead buying a remarkable number of small gifts, such as Hot Wheels toy cars.

They sell for $2 each, or five for $9.

It’s pointing to a frugal Christmas in which retailers are going to have to discount if they want to move goods, taking further pressure off inflation.

Should that happen, rates could turn down even sooner than financial market traders expect, perhaps by the middle of next year.