As Prime Minister Tony Abbott dusts himself down after what might be the first of a number of challenges to his leadership, interest in Japan about Australian politics is acute. Japanese political elites are focused on Australia’s fratricidal tendencies not because they enjoy bloodsport, but because Japan has a significant investment in the Abbott government.

If Abbott loses office, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will, oddly enough, suffer a not inconsiderable setback.

Japan and Australia have long been key trading partners. Since the mid-2000s they have worked actively to broaden their co-operation into the security sphere.

Both sides of politics have supported this process. Then-prime minister John Howard signed a landmark security declaration in 2007. Labor governments inked agreements on defence servicing and information sharing. Within the public service and defence force there is a strong consensus driving closer work in a range of spheres.

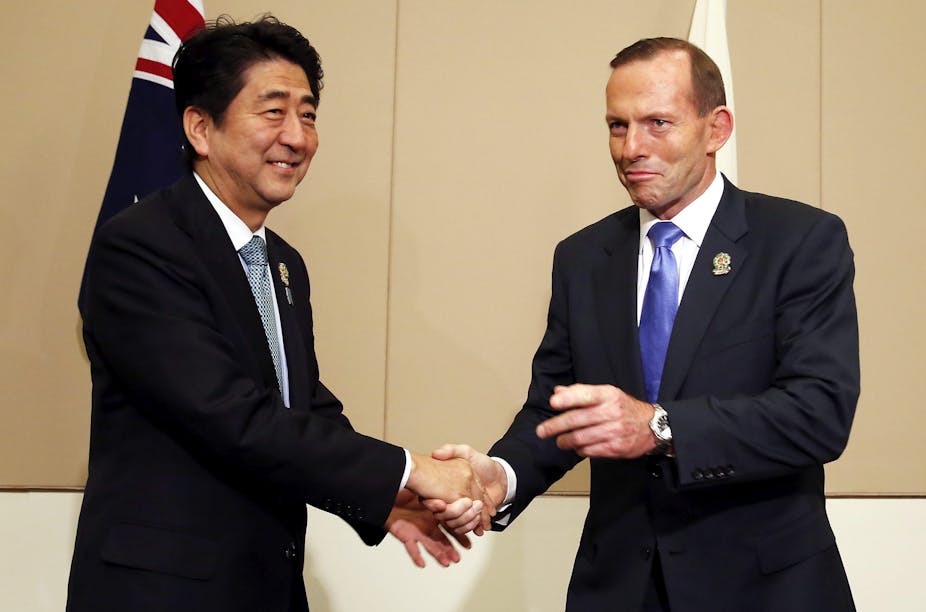

But the election of the Abbott government in 2013 led to a rapid acceleration of activity. Tightening the links with Japan became a fundamental priority for the government. This was perhaps symbolised most clearly with one of Abbott’s first utterances on foreign policy as prime minister – the not-unproblematic claim that Japan is Australia’s “closest friend” in Asia.

Reciprocal state visits in 2014 led to the rapid conclusion of the long-stalled free trade agreement, a defence technology treaty and the prospect that Japan will be closely involved in the development of Australia’s next-generation submarines. Like Abe, Abbott seemed to be in a hurry to strengthen and deepen ties between the two countries.

Many of the recent developments in Australia-Japan relations are not uncontroversial. The free trade agreement did entail considerable movement by Japan, but its conclusion involved Australia giving up many of its aims on agricultural liberalisation. There was much consternation among others negotiating with Japan that Australia had “broken ranks” and eased up pressure on the issue. The logic behind its signature was overwhelmingly political.

Equally, explicitly tying Australia to Japan brought costs in the management of relations with China, Australia’s top trading partner. The submarine links have both domestic and international reverberations. The government seems content to wear the industrial prices of the Japan link while many in the region are uneasy about Australia’s role as an active enabler of Japan’s move to become a defence exporter.

These developments have been almost entirely driven by Abbott. A change, whether to a different Liberal prime minister or to a Labor government, would pose very significant questions about the sustainability of recent trends. For the Abe government, itself re-elected in December 2014, the doubts about Abbott’s longevity as prime minister are very real.

In the most immediate sense, Japan is worried about the prospects of the submarine deal collapsing. Japan’s defence industry is world-class but due to tight political constraints it has not been able to access global markets for its products. Australia’s submarines hold out the tantalising prospect of realising these opportunities for the first time.

The benefits of both financially doing well out of the submarine contract but also industrially learning how to do this kind of business are very substantial. Without Abbott these would be at some risk. To shore up support during the recent challenge, Abbott apparently shifted policy to promise a “competitive evaluation process”. Even with an Abbott government, the deal remains vulnerable to domestic pressures.

But it is in the larger strategic dimensions of the relationship that Abe would feel the loss of his friend. The Abe government is overseeing a significant transformation of Japan’s foreign and security policy. Prompted both by what it perceives to be a dangerous international environment as well as a desire to shift how Japan sees itself, Abe is attempting to create a Japan that has a strategic weight that matches its economic heft.

This move is risky and requires deft political handling and international support. It is here that Abbott has been so vital. Australia’s position in the region – as understood by the current government – and Abe’s vision for the region are almost entirely aligned. This gives Japan a vital international buttress for its controversial and challenging aims.

The relationship with Australia is also seen as a test bed for advancing links with other countries. It is no coincidence that the recent bilateral agreement between the UK and Japan on defence technology collaboration looked similar to the Australia agreement.

Once established, the cutting-edge links in security co-operation – from technology to training and intelligence to cyber – can then be rolled out to other partners globally. If it is to succeed in its strategic and foreign policy ambitions, Japan needs more Australias.

Australia under Abbott has been extraordinarily helpful for Abe’s Japan, itself in a considerable hurry. No wonder there is much concern in Japan if he were to fall from power.