It’s back to school for children in France after the half-term winter holidays, which means a return to a particular teaching tradition: giving English names to students who are learning the language for the first time.

This English name is intended to give students a second identity, providing them with both motivation and a place within a specific cultural universe. In a sense, it’s bit like moving Big Ben into a French classroom.

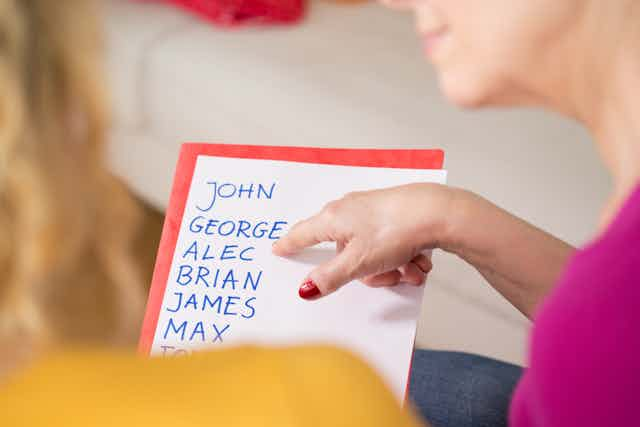

So the children are given names such as Jane, Alison and Betty, or Andrew, George and Peter. Depending on the school, students may or may not get to choose. Some prefer to use their French names in class, with varying responses from teachers. Some teachers accept the student’s decision, others impose the use of the new name. English names can be kept across several years of study and even different schools, or change from year to year.

What’s in a name?

But at a young age, when children’s identity is still under construction, is it really possible to adopt a new name from an unfamiliar culture? In French kindergartens, for example, children’s first names are written by the peg on which their coats hang. They learn to recognise and write out the name, and associate it with their photo – and themselves.

So how should schools manage students who take on a second, scholarly identity? What do such teaching practices tell us about the understanding of the English-speaking world by teachers and students? And do the names given really represent the reality of the culture they are trying to understand?

To answer these questions, I did an informal survey of several language books aimed at seven to nine-year-old pupils, with a focus on English. With the exception of one, all books offered typically “English” names, with none of any other origin, even in the most recent editions.

But England – the reference for publishers of language books for first-year students – is a multicultural nation. There is a large migrant and international populations in Britain, from communities of all cultural backgrounds, including France.

So in such lists, where are the names of Indian or Arabic origin? In Britain, Jack and Harry were the most common boys’ names for a long time, but depending on how you count, the most popular name is now either Muhammed or Oliver, which is of French origin.

Identity politics

As a consequence, French methods of teaching English to children can obscure the genuine cultural diversity of the United Kingdom and so only offer a partial picture of its culture. This is how stereotypes are born.

Through this reduced list of English names, teachers in France are instilling in children an erroneous vision of the United Kingdom from the very beginning. This is a misrepresentation of UK society (or of America or any other English-speaking country).

One of the consequences of shaping students’ choices in this way is to imply that some identities are correct, and others less so. It also influences the value students attach to their own identity. Presumably this practice is well-intentioned, but it’s essentially didactic to the detriment of reality.

Frozen in time

Most often, pupils use their English names in language classes to introduce themselves, according to PrimLangues, a French website providing support to teachers of modern languages. But introducing yourself as “Jane” when your name is actually Aisha or Neweda is anything but easy.

Sometimes, particular names are used to help learn the different sounds of English, as proposed by this list from the Academie Nancy-Metz. This makes sense – English is well known for being difficult to pronounce for many French speakers.

But this list is also only made up of old-fashioned “English” names, such as Laura, Mark, Peter or Samantha. We see neither Indian nor Arabic first names, only a caricature of the English-speaking world. The multicultural reality of the culture being studied is thus neglected.

With all good intentions, these methods of teaching English in France promote a false image of a culture that has been frozen in time. It’s worth thinking twice before giving English names to French students.