After 23 years, the UN Human Rights Office in Burundi has closed – at the insistence of the country’s government. The Conversation Africa’s Moina Spooner spoke to Professor Christof Heyns, who was Chair of the United Nations Independent Investigation on Burundi, about the closure, why it happened and what this means for the country.

The human rights situation in Burundi seems to be deteriorating. What’s happening?

Burundi has a long history of violence between its two dominant ethnic and cultural groups – the usually politically dominant Tutsi minority and the Hutu majority. A civil war that lasted 12 years ended in 2000 as a result of the Arusha peace accords. In 2005 Pierre Nkurunziza, a former Hutu rebel leader, became the first president to be chosen in democratic elections since the start of the civil war in 1994.

But the situation deteriorated in 2015 when Nkurunziza announced, based on a dubious interpretation of the peace accords, that he was entitled to run for a third term. Large protests in the streets of Bujumbura, the country’s capital, were brutally suppressed. Security forces, supported by the youth group Imbonerakure, often took the law into their own hands.

Matters escalated. Opposition parties retaliated and were suppressed. Hundreds were killed and hundreds of thousands fled the country, not least because of concerns that Burundi’s violent history was about to repeat itself. People with moderate views were pushed out of the government and very rough elements took control. Civil society was gutted. Institutions like the Constitutional Court were marginalised and most of the press has been silenced.

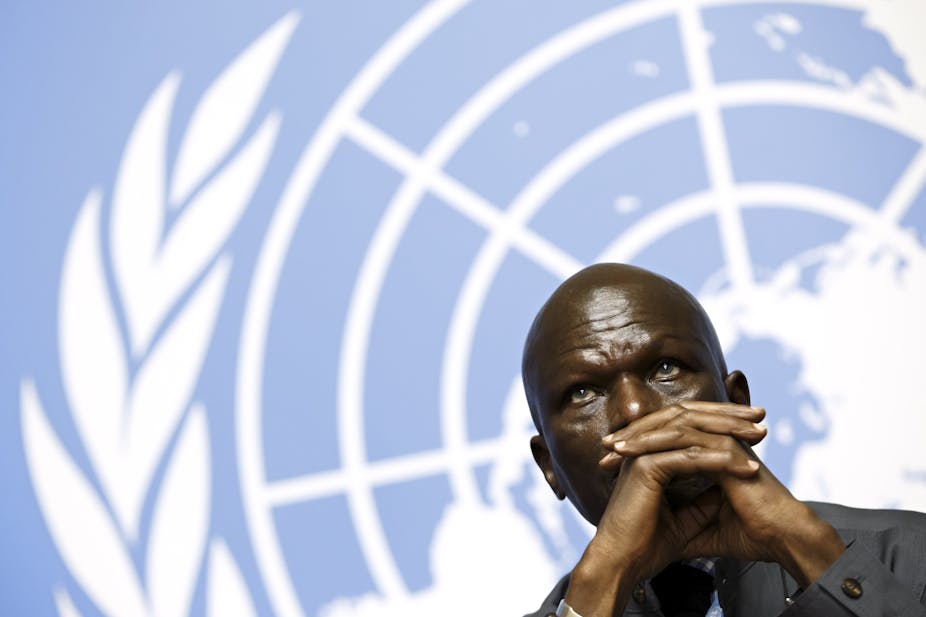

The UN Human Rights Council established the United Nations Independent Investigation on Burundi in 2015 to investigate violations and abuses of human rights in Burundi. When our report came out, those holding onto power ceased to collaborate with the UN human rights team. The government isolated itself further during the last two years. They pulled out of the International Criminal Court, harassed UN officials and independent investigators and even threatened to prosecute them.

What’s brought this about?

I see it essentially as a problem of a lack of leadership. It’s not impossible to bring peace and development to Burundi. But those in power have retreated so far into defending their own narrow self interests that they simply have no interest in working for the common good.

What are the worst developments? Has it ever been this bad?

In sheer numbers it has been much worse before. In 1972 for example, there was a mass killing mostly of Hutus by Tutsis, and in 1993 a mass killing mostly of Tutsis by Hutus. Hundreds of thousands were killed in both genocides.

The current figures have not approached this is any way. Since the crisis started in 2015, the killings are probably now in the low thousands. But looking at it in terms of sheer numbers doesn’t really capture what’s wrong here.

Every life is of infinite value. While a lower number of killings are obviously better it’s not a matter of adding up all the dead bodies to establish how serious the situation is. Even if fewer people are killed, the violence still paralyses the entire society.

The killings take the form of individual targeted assassinations and enforced disappearances of people who are moderate, creative, or simply have different views. The government is depriving the nation of the very “middle ground” people who could contribute to the building a peaceful nation.

Whereas one could somehow conceive of a rationale about who was targeted before -– normally the high profile dissidents, the activists, the opposition and participants in demonstrations and movements - now it could be anyone. Even if you are low profile you could be next. Ordinary citizens are being targeted for not sufficiently supporting the party that’s in power. This takes the life out of the society very much in the same way as large scale killings do.

Are there any glimmers of hope?

Having said the above, the fact that the country has not (yet) descended into the full-scale madness of earlier times is a positive. In my view the presence of the international community, in spite of all the setbacks, has helped to prevent such a slide and served as a damper on the more violent forces at work. So the closing down of the UN office is a serious setback.

The government is also tightening its control over foreign NGOs; it’s put in place demands about the ethnic composition of staff and budget reporting requirements – as conditions for being permitted to continue to operate in Burundi. Several have decided to close down rather than comply. Very few remain.

Burundi is preparing to hold presidential and legislative elections next year. This is sadly not necessarily good news. Elections have often been sensitive periods in the country. Violence, especially ethnic violence, is unleashed and don’t necessarily yield fair results. But what’s the alternative? The stakes are very high. It will be important to assure that Burundi remains high on the international agenda. But the UN doesn’t have a magic formula. In the end nothing can work without responsible leadership within the country.