This week, Russia tested an anti-satellite missile on one of its own satellites, COSMOS 1408, and created a stream of debris that forced the International Space Station (ISS) crew to take shelter in their Soyuz and SpaceX Dragon capsules.

The action has generated widespread international condemnation, including from the US Space Command, US State Department and UK Ministry of Defence. And rightly so; it was an irresponsible and menacing action in the context of recent progress towards global agreements on the responsible use of outer space.

NASA condemned the “irresponsible and destabilizing” missile test, too, saying it had also placed China’s Tiangong Space Station and crew at risk.

Harm to the space environment

The destruction of the COSMOS 1408, a defunct Russian spy satellite, generated more than 1,500 pieces of trackable debris and likely thousands more that are too small to be tracked.

Russia’s space agency, ROCOSMOS, dismissed concerns regarding the debris field, tweeting:

The orbit of the object, which forced the crew today to move into spacecraft according to standard procedures, has moved away from the ISS orbit. The station is in the green zone.

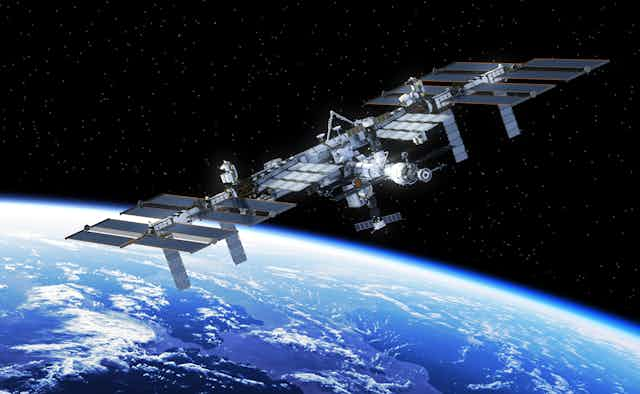

As commercial uses of space have expanded in recent years, access to the low Earth orbit – roughly the altitude zone less than 1,000 kilometres above Earth – has become increasingly important.

The ISS orbits the Earth in this zone, at an altitude of about 420km. The station shares the low Earth orbit with mega constellations of satellites – including the many satellites that form SpaceX’s Starlink internet network.

But there has been growing recognition that our use of outer space is threatened by increasing space debris, much of which has been created by anti-satellite (ASAT) missile tests, generally conducted to demonstrate technological power.

China destroyed its FY-1C weather satellite in January 2007, creating more than 2,000 trackable pieces of debris.

Russia and the US have also undertaken ASAT tests in the past. Before this week, India had conducted the most recent test in 2019, becoming the fourth country to do so.

The issues of space debris and destructive uses of outer space (both of which are linked) pose significant environmental and national security concerns.

The effects of Russia’s latest test will be felt for some time. Although smaller pieces of debris will no doubt degrade and burn up in the atmosphere, the ongoing threat to the ISS and other operators in low Earth orbit will remain.

Studies have estimated 79% of the debris created by China’s 2007 test will remain in orbit until 2108. It’s time to bring an end to these needless displays of power.

The responsible use of outer space

Russia’s action is particularly surprising given the recent progress in the United Nations First Committee towards the development of norms of behaviour in space.

Since the formation of key UN space treaties between 1967 and 1984, there has been little international consensus with respect to peaceful uses of outer space. Also the last of these treaties, the Moon Agreement, received few ratifications.

After decades of stalemate in the UN, progress was achieved last year with the UK sponsoring a draft resolution for the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space.

This month, the draft resolution was approved by the UN First Committee (Disarmament and International Security) by a vote of 163 countries in favour to eight against, with nine abstentions. Notably, Russia voted no.

Despite Russia’s opposition, this resolution was the first success in international efforts towards space security in several decades. Prior failed initiatives included a draft treaty sponsored by Russia and China and another draft treaty sponsored by the EU.

A shifting discussion

The 1967 UN Outer Space Treaty requires that states conduct their activities in space in accordance with international law, and in the interest of maintaining international peace and security. However, the extent of these obligations have remained largely untested.

It says states must “undertake appropriate international consultations” before proceeding with any activity or experiment that may create harmful interference to the activities of another state.

Yet, such consultations are rarely held. And a US Department of Defense spokesperson confirmed no such warning was provided by Russia prior to yesterday’s test.

Concern over Russia’s latest action is noteworthy. Even though international space law doesn’t explicitly prohibit ASAT tests (and countries have previously been reluctant to condemn such behaviour by other states), this development seems different.

Voices are being raised and human missions have been placed in jeopardy. Perhaps recognition is dawning that space is a fragile and finite resource worthy of protection.