It may not seem logical or good value for money, but there are plenty of us that will fork out for expensive presents this Christmas. Maybe it will be close to A$3,000 for premium seats to see Wagner’s Ring Cycle? Or maybe you prefer to spend thousands on fancy white goods like retro inspired coffee machines or fridges?

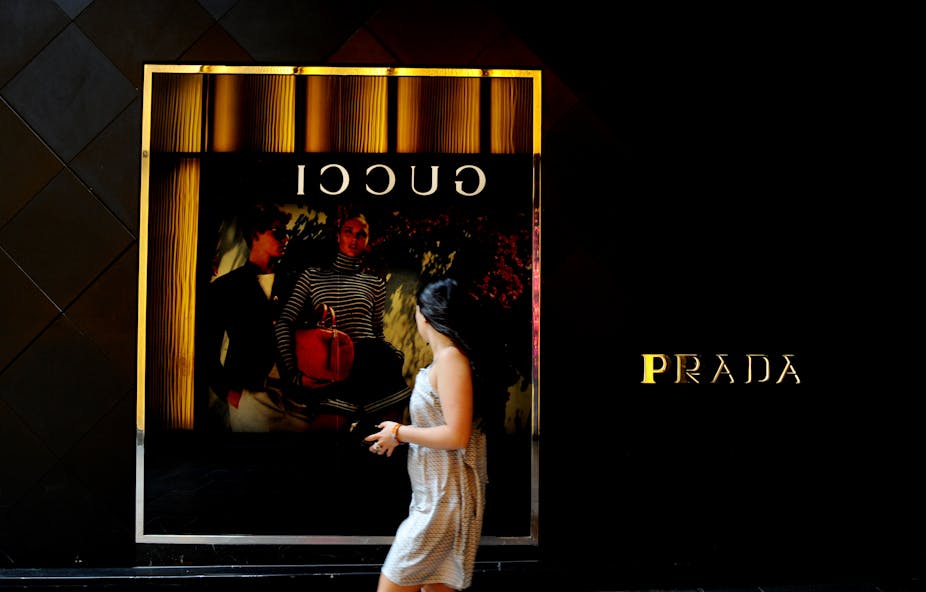

Many of these products may not be considered by you to be luxury products, but they are certainly a product of desire. In reality, nobody “needs” a $700 pair of shoes, or a retro $2000 fridge, but these products seem to transcend their rational utility. They have meaning beyond their function. They are objects of desire that help us to communicate to ourselves and others who we are.

Desire, status and luxury are concepts that have been explored for hundreds of years. Probably one of the best known books about this topic was by sociologist and economist, Thorstein Veblen, published in 1899. Veblen suggested the act of buying expensive things was a means for people to communicate their social status to others. He suggested that the purchase of luxury goods, expensive houses, or attending exclusive soirees was a form of “wealth signaling”, or what others have called “peacocking”.

French philosopher Pierre Bourdieu took this interpretation a step further in 1979, by suggesting that what we buy is a product of our social conditioning. He argued that the objects and things we consume are a means of communicating to others a symbolic hierarchy, as a means to enforce our distance or distinction from other classes of society.

It’s even arguable that our contemporary predilection for all things authentic, artisanal, and bespoke is an attempt at acquiring some meaning in the things we consume. Consumer preferences are rarely the outcome of some innate, individualistic choices of the human intellect, but a more complex, somewhat unclear desire to be part of something bigger than ourselves.

Consumption does not occur in a vacuum. The things we buy, the things we do, the people we associate with, the places we live and the places we visit all possess meaning for us as human beings.

Research can tell us a lot about the contradictions in consumer behaviour when it comes to the purchase of luxury and desired goods. Researchers Hudders and Pandelaere found that purchasing designer handbags and shoes was found to be a means for women to express their style, boost self-esteem, or even signal status. Their research suggested that some women also seek these luxury items to prevent other women from stealing their man.

A surprising finding in their work was that feelings of jealousy triggered a desire for luxury products, not just for women in committed relationships, but also for single women. Many single women obviously want designer products, but instead of these products saying “back off my current man”, the single woman is saying “back off my future man”.

That isn’t to say that only women desire luxury goods. Men, women, old people, young people, poor and rich people, all desire things that others can’t have. For most of us the desire to distinguish ourselves as individuals, among our peers, is built into our DNA. And what we consume helps to make clear that distinction.

It seems humans will always want something that others in our groups don’t have. The fact that we are exposed to, and seek out stories about, success and wealth, has been shown to actually influence how badly we want luxury items.

Another study found that simply reading a success story increased a desire for luxury brands among the study’s participants. What was interesting about this study was the findings weren’t the same in all circumstances. The desire for luxury brands only seemed to be present when the participants read a success story about people that they saw as similar to themselves. The researchers found the participants only desired products and outcomes that they could see themselves achieving.

Media portrayals of wealth on TV, on the news and even in social media have been shown to define consumers’ worlds by creating an image in their minds of what life should be like. This skews their views of reality toward the norms, values, and social perceptions represented in the media that we consume.

In one study, the researchers found that people who watched more television assumed higher estimates of the average level of wealth and affluence in the US. This also led them to believe they were missing out on the tennis courts, private planes and swimming pools they saw represented in the media.

But even for those on low incomes, products are more significant than their simple utilitarian capacity. We buy goods to enhance our lives, to fit in, but also to remind ourselves that we are just a little better than most of our group.

We’re a product of the culture in which we live, and we purchase products to reinforce our connection to that culture. What we desire and what motivates us to buy luxury goods can only be understood by considering bigger human questions.

Viewed through a rational lens, it is pretty tricky to explain why someone would pay A$3,000 to watch 15 hours of opera that finishes where it began, or A$450 for a kilo of steak full of intramuscular fat, or A$1.4 million for a red car that goes very fast.

But being human is more than being rational.