Winnie Dunn’s first novel, Dirt Poor Islanders, takes as its epigraph a line from Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians (2013): “Remember, every treasure comes with a price.”

Like Kwan, Dunn has made it her project to bring a more sensitive intercultural understanding to an unfamiliar readership. The title of her novel is a direct echo of Kwan’s. But where Crazy Rich Asians reworks familiar Western views of modern Asia, Dunn’s novel is the very first novel to be published in this country about the Australian Tongan community.

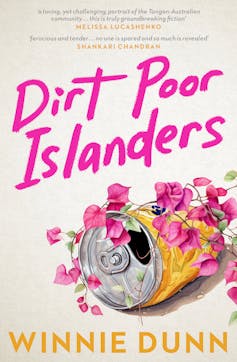

Review: Dirt Poor Islanders – Winnie Dunn (Hachette)

Although Dirt Poor Islanders is her debut novel, Dunn is not new to the literary scene. She has worked with the Sweatshop Literacy Movement, published widely in national and international journals, and edited four anthologies, including Straight Up Islander (2021), a collection celebrating Islander identities and experiences.

That Dirt Poor Islanders draws on Dunn’s lived experience is crucial to its mission. The novel is an impassioned response to dangerous and detrimental stereotypes, such as Chris Lilley’s character Jonah from Tonga. Dunn shows how appreciating the “treasure” of a long and rich cultural heritage has come at the “price” of such reductive impressions, which reflect a lack of interest, empathy and understanding on the part of white Australians.

Whiteness and dirt

Dirt Poor Islanders traces young Meadow Reed’s negotiation of this tension. The novel is a work of autofiction – a blend of autobiography and fiction – which includes metafictional reflections on the genesis of the resulting book.

Meadow is, like her author, a young writer. The first chapter of Dirt Poor Islanders is a story she writes in her “gifted and talented” class. Meadow’s grandmother is teaching her ngatu – a traditional Tongan style of painting on cloth or bark – when the pair are confronted by a racist neighbour.

The development of the story leads to a confrontation with a classmate, but Meadow remains determined to assert the value of her own experiences over stereotypes and assumptions.

Dirt Poor Islanders contributes to a tradition of Australian narratives of young second- and third-generation migrants, often blending autobiography and fiction. These include Alice Pung’s Unpolished Gem (2006) and, more recently, Omar Sakr’s Son of Sin (2022). They go as far back as Melina Marchetta’s Looking for Alibrandi (1992) and Christos Tsiolkas’s Loaded (1995).

Like the characters in those novels, Meadow struggles with her hyphenated identity:

I used to get confused when I tried to tell people that both my parents were mixed-race. Sometimes I said I was full-White and full-Tongan. Being bad at maths, I thought that anything with two halves made two separate yet full wholes.

Although Meadow has Scottish heritage, the only family she knows and loves is Tongan. Her grandfather is present only in the satirical lingering of his Scottish name, Reed – a moniker originally coined to describe those with red hair.

At the same time, Meadow resists and is often repulsed by Tongan ways of life in her own home and the behaviour of her grandmother and aunts. She and her siblings find it difficult to understand their grandmother’s “Tong-lish” dialect, “because we were so third-gen”. After the racist neighbour mocks her grandmother’s bark mats, Meadow refuses to paint with her grandmother again.

But Meadow is even more disgusted by the bugs, dirt and mould that infest the family homes and her body. She is forever picking and squashing the lice that crawl through her hair, watching in fascinated revulsion as her blood bursts out of them. When she eats her cornflakes, she discovers “the darkest cockroach I’d ever seen … [a] six-legged monster”. She rushes outside to vomit the cereal into the gutter.

In one horrifying scene, Meadow’s refusal to eat her grandmother’s traditional cooking results in a confrontation in which the older woman force-feeds the girl until she vomits. It is at this point that Meadow recognises her own abjection, her status as dirt, bug and waste:

I was nothing but a nit who deserved what she got because I was born out of a dying mut and came into this world as the waste of my ancestors. My grandmother, my aunties, my siblings, my mummy Le’o – they all hated me. And I did too. I hated me.

Being both Scottish and Tongan, she thinks, meant “we were made out of – whiteness and dirt”.

Togetherness

Each section of Dirt Poor Islanders is named for something that joins the Tongan people: Bark, Soil, Salt, Blood; each begins with a myth describing the origins of the land and its people.

Despite the cultural insistence that “togetherness was what it meant to be Tongan”, Meadow resents this idea for most of the novel. Togetherness seems to consist primarily of the expectation that the family are together in suffering and poverty, rather than love and community.

Indeed, the “togetherness” is not always upheld. Meadow’s younger step- and half-siblings are excluded from special roles in their aunt’s wedding. She questions her strained relationship with her stepmother. It is only when she recognises the togetherness of “kith and kin – blended not just by blood but by skin and soil too”, rather than perceiving her abjection, that she begins to understand her identity and heritage.

Towards the end of the novel, Meadow travels to Tonga with her grandmother, her aunt and her new uncle. In a scene that brings the abjection and resistance full circle, she refuses to use the dirty toilet outside the family home. She ends up with constipation: a literal blockage or denial of her body.

Her anguish is only resolved when her grandmother takes her to a sacred site, promising “Tonga making betta you”. And her grandmother is right: as Meadow squats on the ground, she realises they are matched in their abjection. She had

witnessed the worst in Tonga, just as Tonga absorbed the worst in me. We were now equals, trying to find the best in each other.

Dirt Poor Islanders is not just a novel about what it means to grow up Tongan, but what it means to grow up as a Tongan woman. Meadow is surrounded by different models of womanhood: her tough grandmother, her weary stepmother, her perfect-in-death mother, her younger sister desperate to be a mother, her many aunts carrying their “excess chub for their offspring”, her favourite aunt Lahi, with whom Meadow shares a name, and whose sexuality is a shameful burden. When Meadow begins to menstruate at the end of the novel, she has learned to embrace this as a precious legacy given to her by all those women before her.

But she also finds connection with and empathy for her father, recognising his youth, confusion and abjection as not unlike her own. “I was destined to have many strong mothers,” she reflects, “but I am lucky to have even just one half-decent father.” It is Meadow’s father who gives her the valuable advice that fe’ofa’aki – the word inscribed above her grandmother’s door on the house gifted to her by her children – “means to love another but it also means to love youseself”.

Meadow ultimately learns to love all of herself. She comes to understand herself not as fractured or hyphenated or abject, but as a product of “the cycling of every speck of dust that made me”.