It was 1930. Winston Churchill was a 55-year-old Conservative Party politician who had been a member of parliament for three decades. He had eventually risen to the position of chancellor of the exchequer six years earlier but, in the peace and prosperity of the 1920s, had done a terrible job. Neville Chamberlain, who, as mayor of Birmingham, had run the city for years, would later manage the treasury much better.

The Conservative prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, was impressed by one man more than the other. When he retired in 1937, Baldwin selected Chamberlain to succeed him.

People liked Chamberlain; he was calm, sober, polite, friendly. Churchill was more inscrutable, as likely to insult as to charm dinner party guests. He drank a lot, reputedly admitting: “I have taken more out of alcohol than it has taken out of me.” He was irascible, self-assured to the point of arrogance, and wilful. Many who shared his conservative politics couldn’t stomach his erratic nature. Chamberlain provided conservatism without the drama. He was much preferred by his peers.

It was 1940. Hitler had torn up Chamberlain’s Munich Agreement, a settlement signed in 1938 that allowed for Nazi Germany’s annexation of portions of Czechoslovakia and the creation of a new territory called Sudetenland. At the height of Chamberlain’s popularity in 1938, and to boos in the House of Commons chamber, Churchill had said of the pact: “You were given the choice between war and dishonour; you chose dishonour and will have war.”

War came, despite a decade where Britain and its leaders (namely Baldwin and Chamberlain) had tried to pretend otherwise. After the invasion of Poland, it was clear to all that Churchill had been right. The king offered him the premiership and both Conservative and Labour MPs shuddered: were they putting the country in that man’s hands?

The ‘black dog’

Little did they know how shaky those hands were. For decades, Churchill had avoided standing too close to balconies and train platforms:

I don’t like standing near the edge of a platform when an express train is passing through. I like to stand back and, if possible, get a pillar between me and the train. I don’t like to stand by the side of a ship and look down into the water. A second’s action would end everything. A few drops of desperation.

Churchill knew it and named it his “black dog”, following Samuel Johnson (who, like many great men, suffered from the great disease of manic-depression).

Churchill was so paralysed by despair that he spent time in bed, had little energy, few interests, lost his appetite, couldn’t concentrate. He was minimally functional – and this didn’t just happen once or twice in the 1930s, but also in the 1920s and 1910s and earlier. These darker periods would last a few months, and then he’d come out of it and be his normal self.

In an early letter to his wife Clementine in 1911, after hearing a friend’s wife had received some help for depression from a German doctor, he wrote:

I think this man might be useful to me – if my black dog returns. He seems quite away from me now – it is such a relief. All the colours come back into the picture.

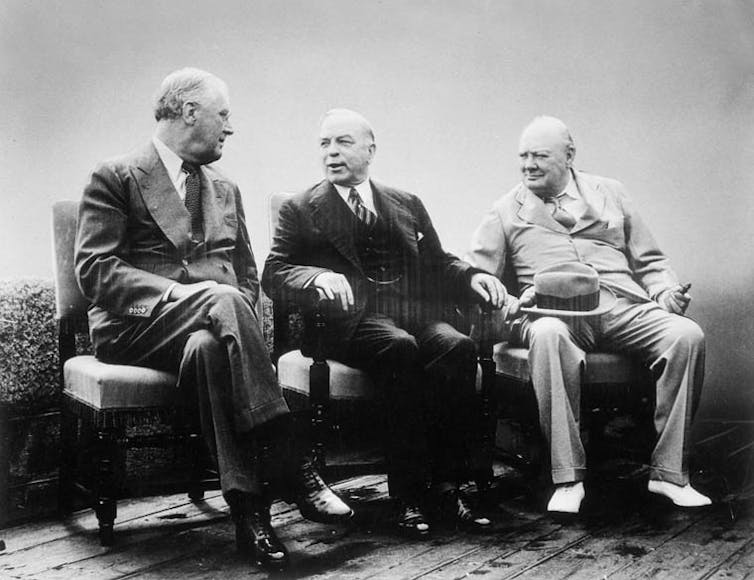

But normal for Churchill was in a sense also rather abnormal: when he wasn’t severely depressed and low in energy and lying in bed, Churchill had very high energy levels. He wouldn’t go to sleep until two or three in the morning, instead staying up and dictating his dozens of books. He would talk incessantly in a tantivy of whirling thoughts. So much so that the then US president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, once said of him: “He has a thousand ideas a day, four of which are good.” These are manic symptoms, part of the disease of manic-depression (which includes but is not exactly the same thing as today’s “bipolar” illness terminology).

After some time, Churchill would go back into months of not talking, not having any ideas, not having any energy. And then he’d be back up again. His mood swings were more than likely related to why Churchill drank so heavily.

To whom fate was entrusted

This was the life of the man to whom the fate of Britain was being entrusted. Britain couldn’t afford Churchill to become depressed and despairing and non-functional for months during the war. Thankfully, there was another man standing behind Churchill: his physician Lord Moran. Moran prescribed amphetamines for Churchill in later years for his depressive episodes and a barbituate from 1940 to help him sleep.

Despite all this, historians haven’t wanted to admit it: how could a great man have severe depression (much less manic-depression, which is likely more correct)? Even the great writer William Manchester in his posthumous 2012 biography, The Last Lion, rejected the evidence of Churchill’s psychiatric disease.

Deify and deny: great men cannot be ill, certainly not mentally ill.

But what if was they are not only ill; what if they are great, not in spite of manic-depression but because of it?

My recent research has suggested that in times of crisis, it is sometimes those who are seen as quirky, odd or with a mental disorder that show the greatest leadership. Mania enhances creativity and resilience to trauma, while depression increases realism and empathy. Churchill was a creative, resilient and realistic leader, and empathic to Jews at a time of common British anti-Semitism.

We don’t want to allow biology into social matters. Churchill was great, we believe, because of some ineffable greatness about him. But we exist in and experience our bodies: We aren’t pure spirits. Biology can have an influence too.

It was late 1940. A shaken Chamberlain had succumbed to metastatic cancer. Churchill, joining the pallbearers, gave his former nemesis a generous eulogy:

In one phase men seem to have been right, in another they seem to have been wrong. Then again, a few years later, when the perspective of time has lengthened, all stands in a different setting.

This article was amended on January 30 2015 to correct an assertion that Churchill was unable to attend parliament because of mental ill health.