This week saw the passing of Sydney-born Richard Neville – Australian enfant terrible of the 1960s, editor of OZ magazine (published from 1963-73) and leading spokesperson for the counterculture.

In looking at Neville’s life, both in regards to his writing and more importantly his activism and public eloquence, his impact on the counterculture movement is clear, and the times were indeed a-changing, as Bob Dylan proclaimed in 1963.

In the early 1960s, a new tension was arising between conservative norms and a generation of students and disillusioned youth who challenged the status quo. As an arts student at the University of New South Wales, Neville became the features editor of the student newspaper, Tharunka, where he gained a reputation for inciting controversy and developing pranks against the university’s vice-chancellor.

Just a few short years later, Neville suggested the idea for a new magazine.

OZ first hit the streets of Sydney on April Fool’s Day 1963, after Neville and a group of friends had informally founded OZ at his family’s Mosman home. OZ courted controversy from issue one, in its merciless satire of the conservative establishment, and for raising issues considered immoral or taboo, such as abortion and sex.

In 1964, Neville and his co-editors Martin Sharp and Richard Walsh narrowly escaped jail terms for charges of obscenity arising from the cover of OZ issue six, which shows the editors pretending to urinate in the recently unveiled Tom Bass sculpture on the P&O building in Sydney.

The 1960s were the beginning of a radical shift in Western society, the repercussions of which are still being felt today.

The anti-war movement, an explosion in recreational drug use, sexual liberation, human rights, freedom of speech, the lessening of censorship, lampooning of politicians and the political process, music, the environment, and adoption of alternative lifestyles; these matters took hold of Neville and his generation as he was let loose in London at the height of the “swinging sixties”.

In 1967 the London-based OZ was launched in Hyde Park. He wrote of the event:

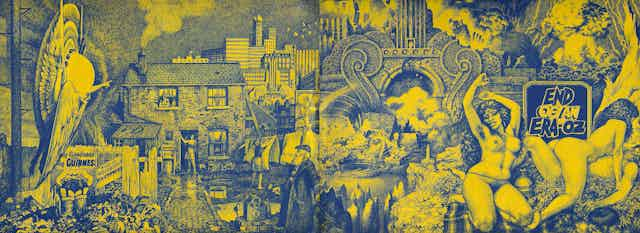

The new OZ, shimmering gold in its karma-sutra gate fold and celebrating free love and spiritual alternatives, matches the mood of the moment.

Supported by friends such as the artist Martin Sharp, Neville was able to turn OZ magazine into an international beacon of the underground counterculture movement, much to the consternation of the authorities. The subsequent OZ trial in 1971 – again for obscenity – took its toll on Neville and fellow editors Jim Anderson and Felix Dennis.

Although the flame of energetic opposition to conservative norms was diminished, it was never extinguished. Upon his return to Australia after 1972 he met his partner Julie Clarke and turned his life to writing, often promoting the counterculture as many of its elements were adopted by mainstream culture.

After several years based in New York writing for The New York Times and other prominent magazines, Neville and Clarke returned to Australia and moved to the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney.

The ideas he was attacked for in the 1960s – from championing solar power to talking openly about sex – gradually crept into the national discourse.

Unlike many of his counterculture contemporaries, he wanted to improve capitalist and democratic systems, not smash them. He shaped a new career as a “futurist”: someone who promoted forward-looking alternatives to outdated conventions, from environmental business practices to how the dole supports the arts.

Neville’s original thinking and creative capacity opened new channels for him, making regular appearances on the Mike Walsh Show in the 1980s. He used this rather conservative platform to continue to challenge Australia’s conservative standard – although his very presence was a sign they was starting to change.

Neville was very much of his time, whether it be the smart-alec university student of the early 1960s who launched OZ Sydney; the drug smoking, long-haired hippie of London and the OZ trial during the late ‘60s and early '70s; through to the family man, writer and public speaker of the '80s and '90s. All his manifestations revealed Neville as a Peter Pan-like figure, full of energy, enthusiasm and cheek.

He played an especially significant role in the cultural transformation of Australian society during an extended period of upheaval from the early 60s through to the late 70s. Much of his activity was recorded in his 1995 autobiography Hippie Hippie Shake, edited with the help of his old London OZ co-editor Jim Anderson.

In recent years he had retired to a quiet life with his wife Julie in his Blue Mountains retreat. When the University of Wollongong approached him in 2014 with the proposal to digitise OZ magazine and making it available to students, researchers and the general public, he approached the topic with his usual enthusiasm.

In an interview the following year he reflected on the significance of OZ and his role on the edge. There was a toll – a number of legal trials, time in a London prison – but there was never any backing away from the importance of questioning the Establishment, putting its activities under a critical spotlight, and using satire to withering effect.

Richard Neville’s death in some ways marks the end of the transformative 1960s. Half a century later much of the spirit of the '60s lives on all around us, though we may be unaware of the debt we owe.