Not long after John Clarke died in April 2017, his elder daughter, Lorin, attended a children’s birthday party where she found herself standing alone.

A woman came up to pass on her condolences. Another woman, a stranger, overheard and squealed. Your dad was John Clarke? “Are you serious? I love him!” Trying to go along with it, Lorin replied, “I love him too”.

The woman looked at her sharply and Lorin thought she was about to be admonished for her dark humour. Instead, the woman leaned in and said: “I don’t think you understand. I grew up with him”.

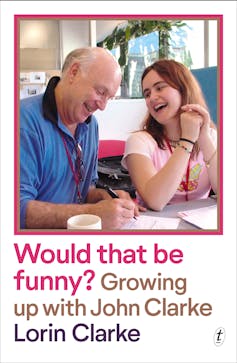

Review: Would that be funny? Growing up with John Clarke – Lorin Clarke (Text)

I know what she means. Along with countless others in Australia and Clarke’s birthplace, New Zealand, I fell in love with his humour, first in the form of Fred Dagg, a gumbooted clodpoll who commented on current affairs in the idiom of the agrarian sector and with a dust-dry, nasal delivery.

In the early 1980s, as part of The Gillies Report, Clarke created the mythical sport of Farnarkeling, featuring the very dextrous but disaster-prone Dave Sorensen who could “arkle from all points of the compass” even while inadvertently backing into a small ice-flattening machine during a lapse in concentration.

He then discovered numerous well-known poets had mythical antipodean counterparts such as Fifteen Bobsworth Longfellow, Sylvia Blath and R.A.C.V. Milne, who he wrote up in The Complete Book of Australian Verse.

Ahead of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, Clarke and Ross Stevenson created The Games, a mockumentary about an Olympics organising committee forced to admit it had built a 100 metres track that was not actually 100 metres long.

Read more: How good was John Clarke? Some reflections on his poetics of tinkering

He was perhaps best known for the mock interviews he did with Bryan Dawe. Begun in print in the late 1980s before running on Channel Nine’s A Current Affair between 1989 and 1996, they aired on ABC television from 2000 until his unexpected death aged 68 while bush-walking with his partner of 44 years, Helen.

Clarke never made any effort to impersonate the politicians and celebrities he satirised. Instead, he fielded questions from Dawe, as himself, while maintaining deadpan that he was someone else. The initial surprise at seeing a middle-aged, balding man wearing no make-up or wig speaking as if he was (then) Prince Charles or actor Meryl Streep was funny itself, especially when the latter engaged the interviewer in chit-chat about the “natural” colour of her/his hair and whether “Meryl” would wear a wig for her role as Lindy Chamberlain in the film, Evil Angels.

More importantly, though, the decision not to impersonate the subjects prompted the audience to focus on what they were actually saying. And that was when the mock interviews transcended pratfalls of the politician-slips-on-banana-peel variety to become a genuine satiric enquiry into the gap between what politicians say and what they do.

Clarke’s work was popular and so was he. His blue eyes and mischievous smile endeared him to many who had never even met him. Patrick Cook, a fellow writer on The Gillies Report, described him in a radio documentary as a living treasure who appeared to have been descended from dolphins.

Into this picture comes Lorin Clarke’s memoir. It’s a tall task to write about someone so beloved and she does it well. Cover blurbs can be puffery but the one provided by Kaz Cooke, a decorated cartoonist/writer herself, is apt: “This beautiful memoir honours love, grief and riotous fun”.

It does indeed. First there is Lorin’s shock at losing a fit, healthy father at such a comparatively young age and the quick realisation just how many people knew and loved him. When she went to pick up letters and periodicals from his post office box, “a drifting tide of Australia Post staff” moved toward her. They all knew him. “Dad knew the names of the woman at the next counter’s kids” and asked about them every time he went in.

Read more: Talking to John Clarke: a friend and biographer reflects

Letters and leckies

John Clarke was notoriously private, shunning the inanities of red-carpet theatre and giving away little in the media interviews he did over the years. Clarke’s memoir offers a portrait of what she acknowledges is an “almost offensively idyllic” childhood in the bush-fringe outer Melbourne suburb of Greensborough for her and her younger sister, Lucia.

They had a father whose work meant he was around a lot and was every bit as funny as you might imagine. Their mother was an art teacher, later a respected, boundary-pushing art historian, and through their house flowed a stream of interesting, creative people who sang and socialised late into the night. This enabled the sisters to talk in their bedroom after they’d been put to bed.

It was a family that loved words and games. Lorin Clarke reprints excerpts from the Clarke/English dictionary. A “leckie” was “the process whereby a (usually male parental) person holds court on a topic for an extended period” while “the Abe” was the ABC. No one in the family ever said the sea was cold, opting instead for James Joyce’s “snotgreen” or “scrotum tightening sea”.

They wrote each other letters deploying a range of argots. John might convert the lyrics of the Beatles song, “All you need is love”, into a news item while Lucia would send a legal letter from a Mr A Garfunkle in which he purported to be acting for his client, Mr Paul Simon.

I understand that you act for Cecilia. I am instructed that your client has broken the heart of my client.

By the time Lorin and Lucia were teenagers and the family had moved to the inner-city suburb of Fitzroy, they self-identified as The Sisterhood and began to notice how irritating it was when their father would launch into a surgically precise demolition of their favourite television program, Party of Five.

For Lorin, torn between wanting to enjoy her show and sensing the critique might have merit, this was infuriating. But Lucia had his number. Knowing that the Bledisloe Cup was an event before which her father genuflected, Lucia would look up from the couch and say, “faux-thoughtfully, ‘I didn’t realise the Bledisloe Cup was an intellectual pursuit’”.

John Clarke hated the “capitalist taste-makers colonising our television screens” while Lorin thought he couldn’t see grey areas or accept the show on its own merits. Later, she discovered he had sometimes listened to her when she overheard him arguing her point to someone on the phone. When she asked him once what he thought of Malcolm Fraser adopting more progressive political views as he got older, John Clarke replied, “Daughters. The man has daughters”.

Over the years several profile-writers have commented on the sparkle in John Clarke’s eyes. The Sisterhood were quick to remind him if was a bit grumpy round the house. “How’s your sparkle this morning, Dad?”

Beneath the sparkling eyes, Clarke railed about the absurdities of anything with a whiff of bureaucracy, an abiding theme in his life as well as his work. Lorin Clarke recalls a flurry of correspondence with the local council over the “final notice” for a parking fine when her father complained he had never received the original notice.

The council explained that since he could not prove that he did not receive the letters, there was nothing the council could do about that. He asked the council to prove they had sent the letters […] Finally, the council received a letter from Dad that included a cheque for the parking fine amount, plus the late fee amount, plus $17.90 ‘so that you can purchase a dictionary, in which I suggest you look up the word “extortion”. Also, please find enclosed my rates’. The council wrote back thanking him but saying they did not receive the amount for the rates. He then wrote back, assuring them he had sent it.

Once, though, Clarke found a bureaucrat with a sense of humour. He engaged in another lengthy bout of correspondence with the local council over its sub-contracted street cleaning company’s inability to actually clean the streets despite raking in plump annual profits.

He complained that he needed to clear the blocked drains in front of his house on numerous occasions and that he might need to request a new garden rake and broom as, “My own, which I have happily supplied along with my labour and time, are showing signs of wear and tear”.

Soon afterwards, the doorbell rang and a man in high-vis handed John Clarke an industrial-strength broom. “From the mayor,” he said cheerfully and left. As Lorin notes, no further correspondence was entered into.

Read more: Farewell John Clarke: in an absurd world, we have never needed you more

Father and son

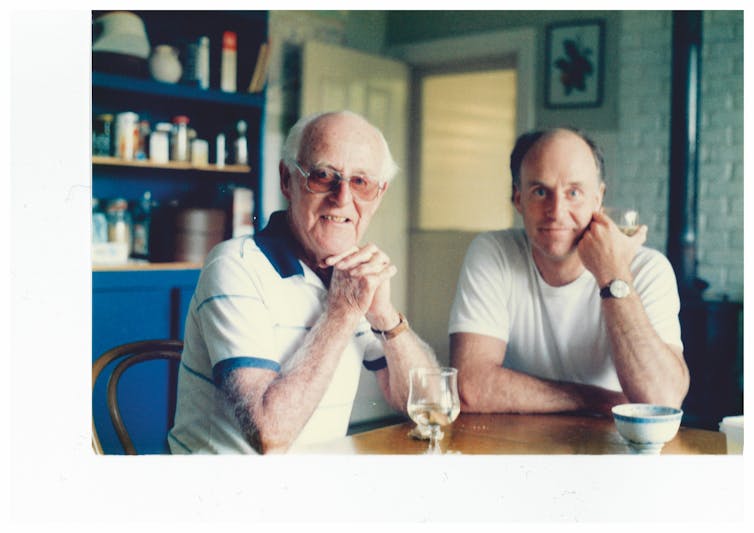

All this is marvellous stuff. What Lorin also sheds light on is the unhappiness her father experienced as a young child after his parents’ acrimonious divorce. John’s father, Ted, appeared for no good reason to blame his elder child (John had a younger sister, Anna) for his unhappy marriage and tormented him psychologically as he grew up.

Ted’s politics were deeply conservative and he presented himself as a “posh British gentleman” even though his son later discovered he was actually “the bastard son of a socialist single mother in Ulster”, Ireland.

It is not clear whether Ted and Neva (John’s mother) were ill-suited or whether, like many, they had been affected by their experiences during the second world war. Ted did not like to talk about it with his granddaughters and only late in life did Neva reveal she had been sexually assaulted by soldiers.

Ted hated the character of Fred Dagg who was the polar opposite of how he presented himself to the world. He refused to attend any of his son’s performances even when the character became prodigiously popular in New Zealand in the 1970s.

“It doesn’t take Freud peering over his glasses to suggest this might not have been an accident,” notes Lorin Clarke. Her “conflict-avoidant” father didn’t think he’d invented the character to annoy his father, but John did admit, once, that he liked annoying certain people, “because if they didn’t like it, it was a sure sign it was working”.

Late in life, though, father and son reconciled. When Ted was incredulous that his son actually earnt a living from his “clowning”, John Clarke took him along to the filming of one of his mock interviews for television after which Ted said, “I get it now. I can see what you do”.

This is a memoir to be grateful for. Lorin Clarke is a talented writer. Well, der, look at her parents, you might say, but being the daughter of an almost universally admired writer is daunting and before this memoir she had already forged her own path. She has numerous credits as a children’s television screenwriter, script-edited a series of the comedy, The Librarians, and wrote an award-winning ABC radio series, The Fitzroy Diaries.

Apart from anything else, Would this be funny? sends you back to John Clarke’s comedy, much of which can still be found here. One of my favourites is a lesser-known series of newspaper articles from the late-1980s entitled “The Resolution of Conflict” about the never-ending negotiations parents engage in with their children.

They are written in the form of a news report, with headlines like “Industrial Unrest Crisis Point”. Here’s a sample:

Wednesday saw the dispute widen when an affiliated body, the Massed Five Year Olds showed their hand by waiting until the temperature had built up and management had about a hundredweight of essential foodstuffs in transit from supermarket to transport and then sitting down on the footpath over a log of claims relating to ice cream. The Federated Under Tens, sensing blood in the water, immediately lodged a similar demand and supported the Massed Five Year Olds by pretending to have a breakdown as a result of cruelty and appalling conditions.

The problem had been further exacerbated by a breakage to one of the food-carrying receptacles and some consequent structural damage to several glass bottles and a quantity of eggs, the contents of which were beginning to impinge on the wellbeing of the public thoroughfare.

Lorin Clarke confirms in her memoir that she was indeed a card-carrying member of the Federated Under Tens. As Fred Dagg would say, I’ll get out of your way now.