Headstones at the Dudley Park cemetery in Payneham, South Australia, were recently bulldozed as part of the ongoing “recycling” of more than 400 graves. Some people were shocked to realise that gravesites are not permanent and many have expressed their “disgust” and concern over the practice.

The reuse of graves is far from a modern phenomenon, caused by exponential population growth and overcrowding in towns and cities. Reusing the same place for burials is a tradition that has been repeated time and again in different cultures across the world, for thousands of years.

Over the entirety of human history, around 108 billion people have lived – and died. That’s a lot of bodies that need disposing of in some way.

In the early centuries of the Common Era (AD), people in northern Europe reused burial mounds from the earlier Bronze Age and Neolithic periods. The catacombs beneath Paris were an 18th century solution to cemeteries that were so overcrowded bodies were stacked on top of one another.

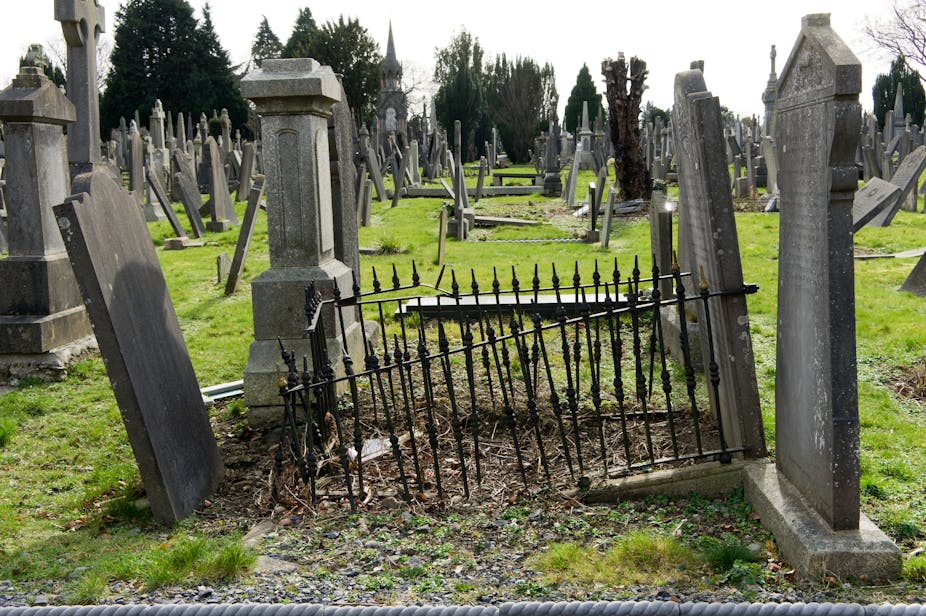

In the 19th century, the garden cemetery movement arose to create more spacious burial grounds — usually on what were then the outskirts of towns and cities. These new cemeteries doubled as places where one could picnic on a Sunday, with children playing games among the headstones and elegant ladies and gentlemen promenading along the avenues.

By romanticising the relationship between the living and the dead the Victorians repurposed the idea of a graveyard from a functional to a recreational space that allowed for continual remembrance of loved ones as part of everyday activities.

Grave concerns

In the contemporary world grave recycling is often driven by economic imperatives rather than purely spatial concerns. If the sole source of a cemetery’s income derives from the leasing of plots — as is the case with many independent cemetery trusts — how are they to remain financially viable when all the spaces are filled?

Cemeteries must serve the burial needs of contemporary local communities, and often this can only be accomplished through destroying older graves so that newer interments can take place.

But what is the boundary between a “grave” and a “heritage site”? This varies across jurisdictions. Under the Burial and Cremations Act 2013 of South Australia, a site may be reused once an interment right expires — usually after a set period has elapsed and if no relative or other party can be found to take on the right (and the payment for it).

In such a case the burial and its headstone are given the “lift and deepen” treatment. The existing burial is removed and replaced lower down in the grave so that another burial can be included on top. The headstone is either smashed and buried with them, or removed to an inconspicuous place.

Before reusing any site, though, the Act requires that details of both the grave and the memorial are recorded photographically and in writing for posterity. Technological advances in recent years means that laser scanning is now a viable option for the recording process and, in all cases, digitisation of the data enables it to be easily made publicly available.

This, at least, retains some of the historical information that contributes to the heritage and social value of these places that would otherwise be destroyed.

If a grave is considered a heritage site, however, different legislation takes precedence. Section 27 of the South Australian Heritage Places Act 1993 affords blanket protection for all archaeological artefacts, whether known or unknown. Any disturbance then requires a permit. Sometimes archaeologists become involved in the process of reclaiming land in cemeteries.

Reuse, recycle, research

Famous Australian examples of the reuse of historical cemeteries in conjunction with archaeological excavation and analysis include the site of Lang Park in Brisbane, the Queen Victoria Market in Melbourne and Town Hall in Sydney.

In Adelaide, the archaeological study of the Maesbury cemetery in Kensington, and the St Mary’s cemetery in the suburb of St Mary’s, have led to unique insights into the burial practices and lifestyles of South Australia’s earliest European settlers.

At Maesbury, only one headstone remained to mark hundreds of bodies now under parkland. This was before a Flinders University archaeology team began work at the site.

It was an exciting day when a neighbour came forth with a headstone they had found while digging in their garden (pictured right) making it only the second headstone to survive.

Research revealed that it had marked the grave of three children from one family who died between 1850 and 1863, in the first few decades of the settlement of South Australia.

Infant mortality was scandalously high in 19th century Adelaide but the causes were mysterious. The gravestone speaks to a grief both public and private, when thousands of children died from the vague disease of “debility”.

At the St Mary’s Anglican Cemetery, archaeologists from Flinders University were invited by the Church to carry out excavations to recover the bodies from a pauper’s area before the land was reused.

This study told us much about the nutritional and health standards of the urban poor. Contrary to expectations, they ate lots of meat (approximately 60% of their diet), but hardly any carbohydrates (wheat or barley). The majority were younger than 15 when they died, probably from infections. Most adult skeletons indicated a hard-working, physically active lifestyle.

As the only study of its kind in South Australia, St Mary’s also highlighted how little we know about the living conditions and lifestyles of South Australia’s early settlers more generally.

All graves contain a story; some touch us more than others, but none of them should be subject to the disrespect of a bulldozer. As George Eliot reminds us, our dead are never dead to us until we have forgotten them.

The Conversation is currently running a series on Death and Dying.