The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is a tiny, spiky package of fat, proteins and genes that was first found in a dying man in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 2012.

Since then, we have learnt a little more about the virus. We know that nearly 90% of infections have originated in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It is lethal in about a third of known cases, most of whom are older males, often with one or more pre-existing diseases of the heart, lung or kidney. So far it has claimed nearly 300 lives.

Camels have emerged as the most likely source of human MERS-CoV infections. In fact, blood samples collected between 1992 and 2013 show camels have been fighting MERS-CoV for at least 20 years.

But, in an unusual twist, research published last week calls on us to seriously consider, or at least acknowledge, that bioterrorism might explain the emergence of MERS-CoV in people. Raina MacIntyre, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at UNSW Australia, suggests that “deliberate release” may explain the paradoxical pattern of ongoing MERS-CoV infections.

“Bioterrorism” is an evocative word; it elicits worry and fear among the wider community and so should be used with care. It is not impossible that bioterrorism is responsible for MERS-CoV, but it is very, very implausible.

MERS is not like SARS

MERS-CoV is often compared with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), which killed almost 800 of the 8,000 people infected from 2002 to 2004. But these are two very different beasts.

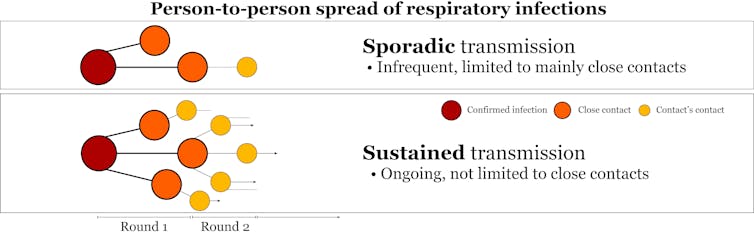

Sustained transmission of SARS-CoV occurred among humans across multiple countries over several months. In contrast, MERS-CoV has a hard time spreading between people at all.

Professor MacIntyre argues these differences suggest MERS-CoV could have been deliberately released. But this doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Any comparison between the two viruses was always going to find them to be different.

MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV have very different genetic sequences, use different ways of attaching to and entering our cells, and have passed through different animals to get to us.

SARS-CoV was detected in civets, and a 95% identical virus was found in Chinese horseshoe bats. Aside from being mammals, the only thing civets and camels have in common is that they sit between us and a likely bat host for the two viruses.

MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV do different things to our cells and immune system and make people sick in different ways. So far they have infected different groups of people, and they have never co-occurred in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. They are like chalk and cheese.

So we know that MERS-CoV isn’t SARS-CoV. That may make the rise of MERS-CoV difficult to explain. But rather than attributing this difficulty to an act of bioterror, it can instead be blamed on the most common barrier to our understanding of emerging infectious diseases: a lack of good information.

Incomplete picture

While MERS-CoV in humans is almost genetically identical to MERS-CoV in camels, it seems much more at home spreading relatively harmlessly among camels, than between us.

If it were a human bioweapon, it would be a terrible one. Most infections by this or that subtle genetic variant of MERS-CoV have come from an infected patient, not from the unknown.

If humans have had a direct hand in the MERS-CoV outbreak then it’s been through lapses in infection control in health-care settings, such as doctors and nurses failing to wear gloves, masks and goggles and not washing their hands.

A trickle of infections that have no link to other human cases has appeared almost continuously over the past 18 months. Professor MacIntyre is concerned that a large proportion of these patients aren’t known to have had contact with camels, either.

Incomplete medical case histories, and occasionally overlooked contact with an undiagnosed case or infected camel source, are better explanations for the emergence of MERS-CoV than the deliberate release of pathogens into the environment. We will simply never know about all relevant contacts for every infected person; we never really do for any viral outbreak.

There may be ten to 100 times as many camels in contact with people in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates than there were civets in contact with people at the time and place that SARS-CoV emerged. It’s not surprising that we are seeing new and ongoing introductions of MERS-CoV into people. Camels offer MERS-CoV far more opportunities to infect people than civets offered SARS-CoV.

More likely scenario

Professor MacIntyre is also concerned that several subtly different variants of MERS-CoV were seen in patients in one hospital outbreak. She suggests that such genetic variability could be a hallmark of bioterrorism.

However, viruses do change over time. And the genetic variability that has been seen in MERS-CoV is squarely within our expectations of what nature can produce. In fact, a very close relative of MERS-CoV was recently found in a South African Cape serotine insectivorous bat, suggesting that an ancestor of MERS-CoV may have evolved in bats.

Something else puzzling experts is the apparent drop-off in MERS-CoV cases during some of the worlds’ biggest annual mass gatherings, hosted by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Ramadan and the Hajj. One could reasonably expect that a communicable disease such as MERS-CoV would spread widely when given the twin opportunities of many people gathered in close proximity.

But, presumably because MERS-CoV spreads so poorly, no surges have been reported to date. These slowdowns also exemplify why a deliberate release scenario is more the stuff of movies, or that the alleged perpetrators of this plague are really bad at the “terror” part of being bioterrorists.

While patience is sometimes hard, it’s often better to wait for the next research result than to contrive an unsupportable theory in the meantime. The one thing we can reliably predict about emerging viral outbreaks is that they’re unpredictable. Unpredictability is rarely by design.