History, they say, is written by the winners – but more concretely, it is written on the basis of the records that survive and are accessible to historians. For most of human history, these have recorded the deeds of kings and queens, pharaohs and prophets, but told us comparatively little about everyday life.

That’s why archaeological finds of items as mundane as the cuneiform tablets of ancient Uruk, recording the inventories of its food stores, or the pot shards of Deir el-Medina, providing medical prescriptions for the workers of Egypt, are so valuable – they offer direct glimpses of how ordinary people lived and worked during those times.

But even in much more recent, much better-documented times, historians have still had to go to great lengths to gather the documentary evidence required to fully understand historical events and actors. From the US Civil War to the Holocaust and beyond, they have initiated projects to collect the letters written by ordinary people during extraordinary times – and of course they also draw on print, radio, and TV journalism, if those records are still available.

Beyond Journalism’s Draft of History

Indeed, journalism has long been described as “a first rough draft of history”: collectively, what they report on represents journalists’ first take not only on what their readers, listeners and viewers need to know now, but also on what is relevant to record for the future.

But in a complex world, such judgments are rarely straightforward. The reality of anthropogenic climate change has taken years, even decades to sink in – and some people, including some journalists, still choose to live in denial. The domino effect leading from unsound lending practices in the US mortgage market to the election of the Syriza government in Greece would have been difficult to foresee, and so the early stages of the crisis received less coverage than in hindsight they should have. And the various impacts of these developments on the lives of millions around the world cannot be documented by journalists alone.

Neither, these days, do they need to be. The past decade has seen an unprecedented shift towards what Manuel Castells has described as “mass self-communication” via social media. Hundreds of millions of users around the world are publicly or semi-publicly recording what matters to them, from (apparently) mundane activities to major world events.

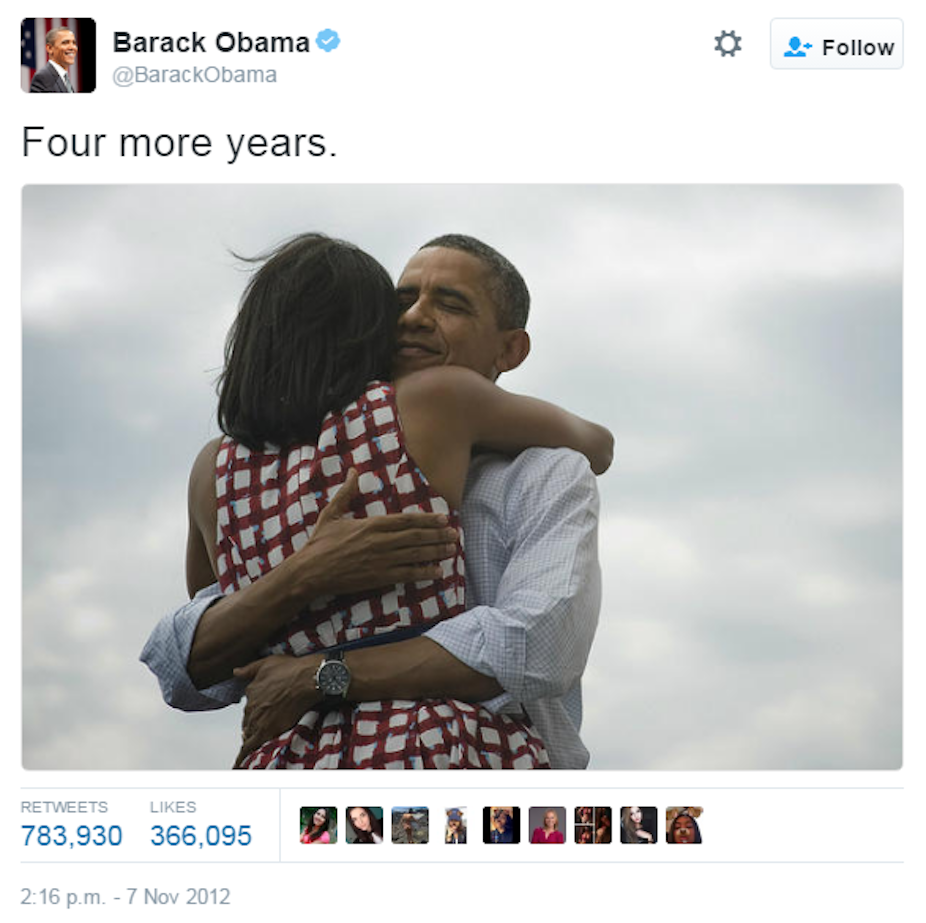

News of earthquakes in Nepal and terror attacks in Paris now breaks on Twitter even before journalists have arrived at the scene, and some events – such as the attack on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan – were even covered purely by accident, as bystanders remarked on the unusual military activity in the area. Elsewhere, the immense social media response to events from the British royal wedding to the death of Prince serves as a better reflection of public sentiment than any obituary ever could.

In their ability to instantly gather and coordinate the collective public response to current events, then, social media don’t just write history. They represent something much more immediate: social media are a first draft of the present, as my colleague Katrin Weller and I argue in a paper for the Web Science conference in Hannover in May 2016. But like all drafts, theirs is fragile and easily lost – a loss which, we believe, would impact significantly on future historians’ ability to understand the story of humanity in the early twenty-first century.

What follows from this is an acute need to address the preservation of social media content. This is complicated by the considerable volume and rapid growth of such archives, and the inherently proprietary nature of the leading social media platforms: both create substantial technical and organisational challenges for any large-scale archiving project.

Current Archiving Projects

Perhaps the most widely known social media archiving project commenced when in 2010, Twitter ‘gifted’ a continuous archive of all public tweets since its launch in 2006 to the US Library of Congress. Beyond the initial fanfare, which generated some much-needed positive PR for Twitter, not much more progress appears to have been made, though. A 2013 update on the Library’s blog made positive noises about the development of the archive, but by 2015 researchers still hadn’t been granted access. Washington insiders Politico called the Library’s Twitter archiving project “a huge #FAIL”, blaming the Library’s poor understanding of emerging technologies.

Closer to home, the Australian Research Council has funded the TrISMA project (which I lead), which has built the infrastructure to track the public posting activities of the nearly three million Australian Twitter accounts identified so far, and the public debates unfolding on Australian Facebook pages. To date, it has captured more than one billion tweets posted by Australians. Led by Queensland University of Technology and supported by a consortium of Australian universities, the project also collaborates with the National Library of Australia, which will eventually house an archive of the full collection, and preserve it for future use.

Such projects must necessarily be speculative in their approach to archiving social media’s first draft of the present. The future remains largely unpredictable, and we cannot foresee which part of the social media record future historians may be interested in. Where will the next Curie or Einstein, the next Björk or Bowie, the next Obama or Malala come from? We don’t know, but we’ll want to preserve their own social media activities, as well as the public response to them.

The Path Ahead

The best solution is therefore to capture all that we can, as comprehensively as we can, and to let those future historians make their own choices from the available record. Some might argue that platforms like Facebook and Twitter themselves already do so: that their proprietary archives are necessarily the most comprehensive, and that no additional archiving efforts are required. But because they are proprietary, these archives are largely closed even to publicly funded, public-interest research – and their longer-term survival is inherently tied to the fortunes of the companies that own them. As past cases from GeoCities to MySpace have shown, even Facebook and Twitter may not be around forever.

The great journalism scholar Herbert Gans once wrote that, as they choose what information makes it into their first draft of history, “the news may be too important to leave to the journalists alone”. The same is true for social media: its first draft of the present is too important to leave to social media platforms to preserve. It’s high time to address the task of building comprehensive archives of our public communication through social media, in order to document our present for the benefit of future generations.