Studies say that development depends a lot on government capacity. However, it is not only government planning that influences the direction of a country’s development plans. Regional geopolitics is often also an influence.

We are seeing a shift in political and economic power from Western countries (Europe and the United States) to Asia (China and India). Being aware of the influence of geopolitics on Indonesia’s development agenda and using the country’s foreign policy to support national development will equip Indonesia to navigate this power shift.

Foreign policy and development

Foreign policy is closely related to development. In the last decade, China has used foreign policy to support its economic development. We can see this in the giant Belt and Road Initiative, a global development strategy that focuses on connectivity and co-operation between Europe, China and Asian states.

Other countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada also have merged their foreign ministries with their trade ministries.

Indonesia should integrate foreign policy with national development, by aligning the work of the Foreign Affairs Ministry with the country’s development agency, the Ministry of National Development Planning.

Development planning can provide guidelines for Indonesia’s foreign policy in searching for good partners. It can also guide the Foreign Affairs Ministry to design partnerships and diplomatic strategies in multilateral forums.

Regional geopolitics

Aligning development planning with foreign policy is important for two reasons.

First, the influence of the US and its allies in Southeast Asia is waning, especially after the global financial crisis that hit almost all of Europe and North America in 2007-2008. The crisis caused the nations of these regions to reduce their involvement in supporting international development in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

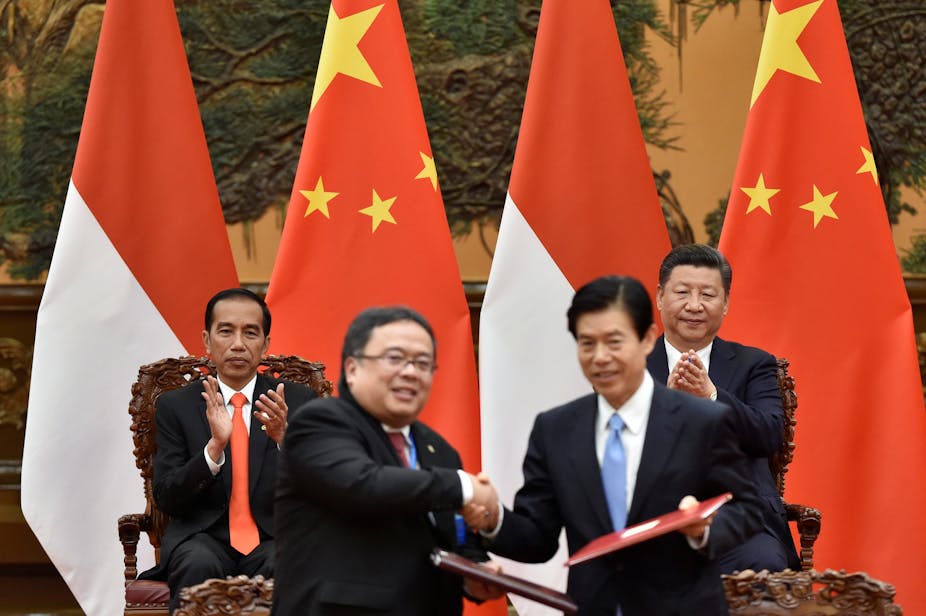

Second, China is on the rise. In 2013, President Xi Jinping launched a program that he calls China Dream, which has been translated into the One Belt and One Road (OBOR) Initiative. Through the manufacturing industry, China expanded economic co-operation (especially in infrastructure and trade) with strategic partners in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

China’s outward foreign direct investment increased from US$45 billion in 2004 to US$613 billion in 2013. Some 68% of that is invested in Asia and 23% is split between Africa, Oceania and Latin America.

China’s international profile continues to rise in Asian and African countries. This indirectly “challenges” US and European domination in those regions.

Indonesia in the middle of battle

Indonesia should respond to this shift of power more seriously, in the context of both foreign policy and development. Being the world’s fourth-most-populous country makes Indonesia vulnerable to becoming a battleground for influence between countries such as China and the US. Indonesia should respond through a development strategy that can adapt to a dynamic map of shifting powers.

Between the late 1960s and early 2000, Indonesia’s development policies were largely influenced by Western economies that encouraged free trade and free flow of capital between countries. Moreover, from the 1980s, Indonesia transformed its economy by gradually loosening government control over the market and expanding the financial sector.

Globally, this was aligned with the growth of the US financial sector. This was built from the post-Bretton Woods system, a global consensus to abandon states’ capital controls, which allowed the financial sector to grow rapidly in developed and developing countries.

But Southeast Asian countries could not sustain this financial architecture during the financial crisis of 1997-1998. In European countries and the United States, the system faced the same blow in 2007-2008, which is still being felt today.

The Asian financial crisis prompted Southeast Asian countries to create the ASEAN Economic Community. The European and North American financial crisis resulted in the Basel Consensus, which redefined government’s role in regulating the banking and financial market.

This shows the global economic architecture is basically dynamic. Development strategy needs to adjust to this architecture. This will ensure the country’s foreign policy is integrated with the national development strategy.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo has pushed for infrastructure development – building roads, bridges, ports, etc – as one of his main agendas.

But Indonesia needs to realise that the push for infrastructure is not only driven by domestic demand to build public facilities, but also connected to the interests of countries producing raw materials and their global economic power.

So far, foreign policy has focused more on Indonesia’s international image and protection of Indonesians abroad. Moving forward, Indonesia must also use its foreign policy to support development strategies. Stronger co-ordination between the Foreign Affairs Ministry and the Ministry of Development Planning is vital.

Looking for Indonesia’s place in the world

In an interconnected world, the global geopolitical order inevitably has an impact on Indonesia, including its national development.

The infrastructure development that President Widodo is pushing is connected to China’s pursuit of global leadership, the move towards industrialisation, the increasing demands for infrastructure co-operation, and the waning of the financial sector after the global financial crisis.

Foreign policy that can map and respond to this shift will help Indonesia navigate the geopolitical power shift. A synergy between the institutions overseeing foreign policy and national development becomes important. Indonesia should start to act now to hold its place in the world.