Inland Australia’s complex system of winding rivers, extensive wetlands, ancient waterholes and seemingly endless parched floodplains are rarely given more than a passing thought by many Australians who live on the coastal fringes.

Yet these waterways are lifelines along which communities, agriculture and trade have flourished.

Etched into the psyche of regional Australia, these river systems are the pulse of the outback. Before asking a local how things are going, peek over the bridge in town for an indication.

Read more: Sure, save furry animals after the bushfires – but our river creatures are suffering too

When relaxing in the shade of an old river red gum alongside one of Australia’s lazy inland rivers, it’s natural to think of them as timeless and resilient to environmental change.

Yet, these rivers evolved over millennia and continue to change over years and decades.

And we already know from previous studies that future climate change is likely to reduce stream flow and water availability in drylands around the world.

But what our new research has shown, for the first time, is that these declines in stream flow may trigger a dramatic change in the physical structure and function (the geomorphology) of Australia’s inland rivers.

Meandering rivers and flat, wide floodplains

The physical structure of a river depends on how much water flows through it, and the sediment that water carries.

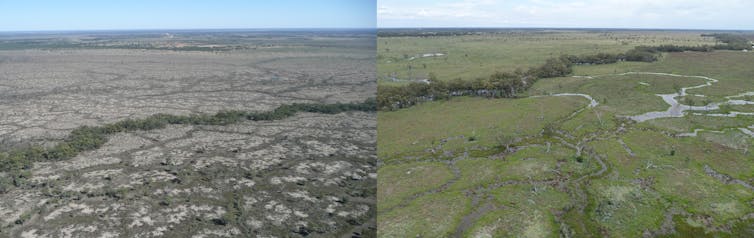

Reductions in water flow – as expected due to climate change – can lead to a build-up of sediment downstream. In extreme cases, this “silting up” can cause complete disintegration of river channels, where water flows out across the floodplain.

Not all rivers are alike, and the rivers of the Murray-Darling and Lake Eyre basins (covering 1.8 million square kilometres) are particularly diverse. Many of these rivers and wetlands are internationally recognised for their hydrological and ecological importance.

Read more: No water, no leadership: new Murray Darling Basin report reveals states' climate gamble

They range from large meandering rivers swollen by seasonal spring flows (the Upper Murray, Mitta Mitta, Kiewa, and Ovens rivers), to rivers that progressively get smaller until they become exhausted on flat, wide floodplains and disintegrate into large, boom-and-bust wetlands (the Lachlan, Macquarie, and Gwydir rivers).

In the drier areas of central Australia, rivers typically persist as a string of isolated waterholes for years at a time, occasionally punctuated by very large floods (Warrego, Paroo, Diamantina, and Cooper Creek).

A sobering future

For Australia’s inland rivers, the average dryness, or “aridity”, of the catchment is the best predictor of what the overall structure and function of the rivers within look like.

Compiling a range of climatic data, we modelled aridity for the Australian continent in 2070 under a relatively moderate climate change scenario.

The results are sobering. Over the next 50 years, the arid zone – containing the areas of true desert – is projected to expand well into the Murray-Darling Basin and almost entirely envelope the Lake Eyre Basin.

At the same time, the humid and dry subhumid fringes around the Great Dividing Range and coastal areas are expected to contract.

This is concerning because the relatively wet western slopes of the Great Dividing Range are where many inland Australian rivers begin, with most of their water sourced in these smaller sub-catchments.

Evolution of our inland rivers

The impact of this projected drying pattern on Australia’s inland rivers is expected to be profound.

Despite only occupying around 3.8% of the Murray-Darling Basin, the Upper Murray, Mitta Mitta, Kiewa, and Ovens rivers presently provide a large amount of flow within the lower Basin (33% of average annual flows).

These rivers flow out of the southeastern highlands towards the Murray River, but over the next 50 years they’re expected to experience declining downstream flows. This leads to less efficient flushing of sediment downstream, which, in turn, will increase sediment deposition within these rivers, reducing their size.

Other rivers – such as the Murrumbidgee and Macintyre rivers – are expected to undergo even more dramatic changes to their structure and behaviour.

Right now these rivers maintain a winding course to the central Murray and Barwon rivers, respectively. But our projections suggest these continuous channels won’t be supported, and are likely to be interrupted by sections of channel breakdown.

Under a drier climate, rivers such as the Lachlan and Macquarie may come to resemble present-day central Australian rivers – only persisting as disconnected waterholes for long periods of time, with internationally important wetlands (Great Cumbung Swamp and Macquarie Marshes) much less frequently inundated.

Read more: The sweet relief of rain after bushfires threatens disaster for our rivers

Such changes to river structure and function will have long-lasting impacts on water, sediment, and nutrient distribution. This will likely change the dynamics of the river ecosystem, as well as the way we manage and use these rivers.

A parched future

While our research hasn’t investigated the potential ecological, socio-economic or cultural effects of structural changes, we can expect them to be very significant, and potentially irreversible.

Read more: Don't blame the Murray-Darling Basin Plan. It's climate and economic change driving farmers out

Many of Australia’s native aquatic and dryland flora and fauna are adapted to a highly variable climate regime, but there are limits beyond which these ecosystems cannot recover or survive. For example, seeds and invertebrate eggs can survive many years buried in dry soil waiting for a flood, but if water doesn’t come, eventually they won’t be viable.

What’s more, extracting too much water from our inland river systems for agriculture or other uses will exacerbate the threats posed by a drying climate.

Given the complexity and tensions surrounding water use and water sharing in Australia’s inland rivers, particularly in the Murray-Darling Basin, understanding how these critical systems might respond in the future is now more important than ever.

Water is one of the most contested resources in Australia, and it’s the fundamentally important river and wetland ecosystems and agricultural industries that will bear the brunt of a drying climate.

To make sure outback communities can continue to survive, it’s vital we protect their lifeline. Water resource planning must include consideration of climate change, as the projected changes will likely increase pressure on already vulnerable systems.