Welcome to the first edition of Beating Around the Bush, a series that profiles native plants: part gardening column, part dispatches from country, entirely Australian. Read more about the series here or get in touch to pitch a plant at batb@theconversation.edu.au.

The Bunya pine is a unique and majestic Australian tree – my favourite tree, in fact. Sometimes simply called Bunya or the Bunya Bunya, I love its pleasingly symmetrical dome shape.

But what I really love about it is that there are just so many bizarre and colourful stories about this tree – the more you learn, the more you find it fascinating. (That is, unless the tree has harmed you; they come with some hazard warnings.)

Read more: Curious Kids: Where did trees come from?

Can you grow it?

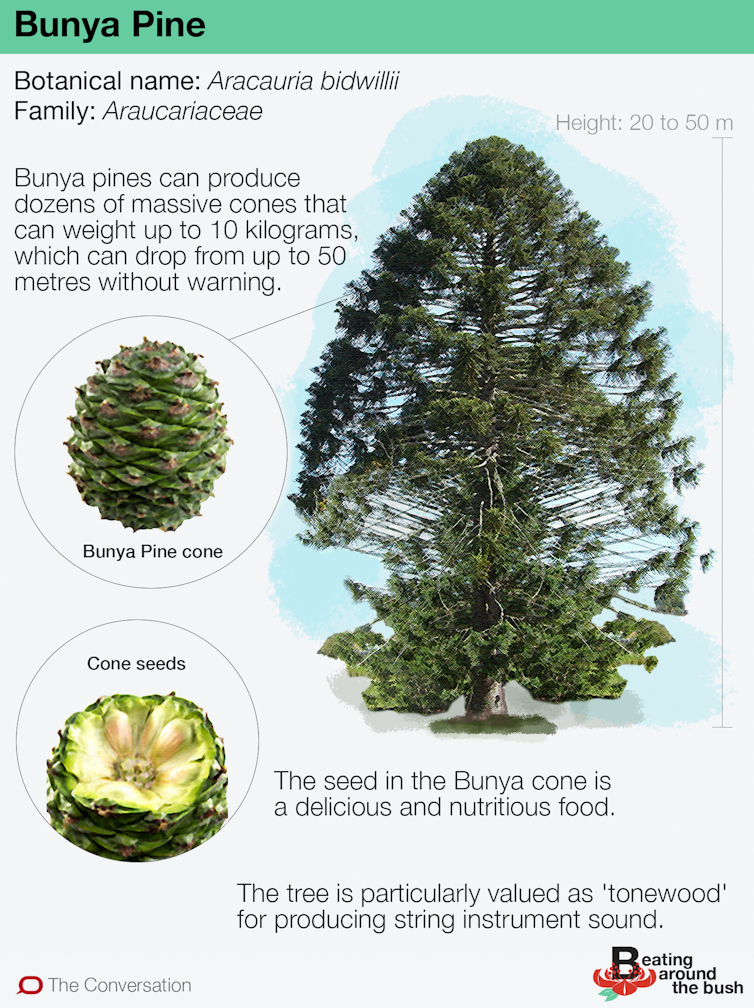

Bunya pines (botanical name: Aracauria bidwillii) are living fossils. They come come from a fascinating family of flora, the Araucariaceae, which grew across the world in the Jurassic period. Many of its “cousins” are extinct. The remaining members of the family are spread across the former landmasses of Gondwana, particularly South America, New Zealand, Malaysia and New Caledonia, as well as Australia.

This family includes one of the most amazing botanical discoveries of the 20th century, the Wollemi pine (Wollemia nobilis).

Read more: Where the old things are: Australia's most ancient trees

Bunyas used to be much more widespread than they are now. Today they grow in the wild in only a few locations in southeast and north Queensland. One such area, the Bunya Mountains, is the remains of an old shield volcano – about 30 million years old, with peaks rising to more than 1,100 metres. The Bunya pines grow in fertile basalt soils in this cool and moist mountain environment.

If you want to grow a Bunya, I would suggest that you need a large garden. The tree needs fertile and well-drained soil, and regular watering in drier climates. A shaded position will also help – it can struggle in direct sunlight in its youth.

Bunyas also produce highly valued timber, which is used for musical instruments. It is particularly valued as “tonewood” for producing stringed instruments’ sound boards. Saw logs for Bunyas come from plantations only, as they are protected in their national park wild habitat.

Stand well back!

While many people love Bunya pines, this love affair comes with a health warning. They are best regarded with both distance and respect!

The trees are big and typically range from 20m to 50m in height. Their leaves have strings of very rigid and sharply pointed leaves. If you come into physical contact with its leaves or branches, you must wear protective clothes and carefully handle them to avoid pain or even cuts. As a child, the swinging branch of a Bunya made a formidable garden weapon.

But that is nothing compared to this tree’s ability to hit you on the head, possibly with serious consequences. When in season (generally December to March) they can produce dozens of massive cones weighing up to 10 kilograms. These can drop from up to 50m without warning.

I first learned of this when a fellow university student in the 1980s scored an impressively large Bunya cone dent in the roof of his battleship-solid FB Holden ute. My university campus has beautiful gardens displaying dozens of massive Bunyas, but one was perhaps a bit close to the car park. My university friend was lucky not to get hit. Many people have not been so lucky and some have even been hospitalised.

Bunya pines are beautiful trees in large gardens and are a feature of parks around Australia, but their habit of “bombing” people and property causes considerable angst. Many local councils erect warning signs or rope off the danger zone during cone season. Others hire contractors to remove the cones to protect their residents (and perhaps limit their own legal liability). Sadly, some Bunya pines have been cut down to remove the risk.

Indigenous use

The cultural connection of the Bunya pine to Aboriginal Australians is very powerful. The Bunya Mountains in southeast Queensland used to host massive gatherings of Aboriginal groups.

People came to visit the Bunya pines and feasted on the nuts in their abundant cones. Some travelled from hundreds of kilometres away, and traditional hostilities were dropped to allow access. The seed in the Bunya cone is a delicious and nutritious food, a famous and celebrated example of Australian bush tucker.

Today some trees remain marked with hand and foot holes that Aborigines made in the trunks of older Bunyas. The climbers must have been brave and agile to harvest the cones from such heights.

Sadly, the last of the Aboriginal Bunya festivals was held in about 1900, as European loggers came to the area for its many timber resources.

But even those European timber pioneers realised the significance of the Bunya Mountains area. The Bunya Mountains National Park was declared in 1908, creating Queensland’s second national park.