Extreme heat is taking an increasing toll across the U.S. in summertime. People who are incarcerated are among society’s most vulnerable groups and have been especially affected. During Texas’s June 2023 heat wave, at least nine inmates died in prisons lacking air conditioning of heart attacks or unknown causes.

More than a dozen states do not have air conditioning in all of their prison units, including Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia. In Texas, where I work, only about 30% of prisons are fully air-conditioned. Many of these states also face some of the highest heat risks in the U.S., according to recent studies.

Prisons concentrate hundreds or thousands of people in buildings that were designed without planning for extreme heat and heat waves. Prison building materials and designs can increase exposure to heat for people inside.

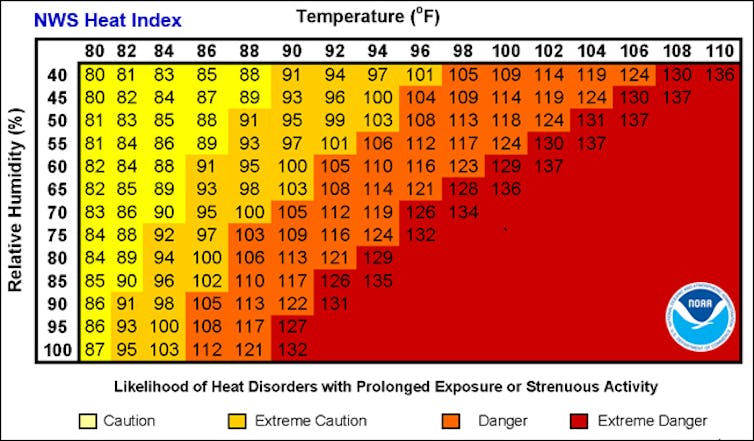

Some states require prisons to maintain indoor temperatures within certain ranges. Texas does not regulate temperatures in prisons, but county and private municipal jails overseen by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards must be kept between 65 and 85 F (18-30 C). There are no comparable federal standards.

I study how hazards and disasters affect people who are incarcerated. In a recently published report, my colleague Benika Dixon and I partnered with Texas Prisons Community Advocates, a nonprofit that works to improve conditions in Texas prisons, to find out how incarcerated people in the state experience heat without air conditioning.

Surveys that we collected between late 2018 and 2020 from over 300 people in state prisons in Texas showed that many of them grapple with the health impacts of heat, and that prisons are struggling to prevent heat-related illnesses and deaths among prisoners. Prison staff are also exposed to extreme heat.

Minimal resources for cooling

High temperatures are particularly dangerous in prisons because incarcerated people tend to be more vulnerable to heat. People in prison have high rates of chronic illness, mental health conditions and disabilities, and a large share are over the age of 50.

In Texas, at least 23 incarcerated people have died from heat illness since 1998. Heat exacerbates other underlying physical and mental health conditions, so the actual number of heat-related deaths in Texas prisons is likely much higher.

In prisons without air conditioning, staff can’t prevent incarcerated people from being exposed to heat. Fans and blowers do little to actually lower temperatures inside units.

Instead, staff provide water, ice, additional showers and access to limited zones that have air conditioning. These so-called “respite areas” often are prison education buildings, chapels and infirmaries. Prison staff also perform wellness checks on prisoners who they have identified as particularly vulnerable to heat.

Not enough water or cool spaces

Many responses to our surveys described facilities with too many people and not enough resources. Examples included not being able to get water because coolers in common areas were constantly running out, or not being able to get into cooled areas of prisons because these zones were already full.

One incarcerated man wrote, “They refill coolers every 2 or 3 hours. But with over 100 inmates drinking they never stay full more than 20 minutes.” An incarcerated woman reported, “It’s very difficult to get access to respite – only 10 spots available.” Nearly half of the incarcerated people we surveyed reported having been denied access to cooled respite areas.

Personnel shortages make it hard for prison staff to keep water coolers full and provide extra showers and time in respite areas. As one respondent commented, “Staff, not enough staff, or they’re too busy or out of time. They only set aside a certain time period [for time in respite areas] because it will interfere with their duties.”

Prison staff suffer too

In Texas, prison staff levels are at a historic low. In 2021, the turnover rate for correctional officers in Texas prisons was over 40%.

In a hearing before the Texas House Appropriations Committee on Aug. 4, 2022, former correctional officer Clifton Buchanan stated, “Temperatures at units can reach well above 110 degrees during the summer, and staff must endure this heat while wearing safety equipment, such as stab-proof vests.” Because of staffing shortages, Buchanan said, officers are “constantly conducting rounds with no break.” He told the committee that he had shifted to working at a federal prison solely because it was air-conditioned.

In our survey, incarcerated people described frequent conflicts with prison staff over access to water, showers and cooling areas. One wrote, “Majority of the time we have to argue with guards to no avail about getting ice or even water.”

Another wrote, “The guard will refuse us if it’s too crowded. Our respite area only holds 20 people. We have 2,014 people who have to share it.”

Our report describes frequent tense exchanges between incarcerated people and prison staff. In his testimony before the Texas Legislature, Buchanan warned that such confrontations could lead to violence.

Nowhere to go

Prison agencies often assert that their heat mitigation policies are adequate for keeping incarcerated people safe. For example, a spokeswoman for the Texas Department of Corrections recently commented, “Much like those Texans who do not have access to air conditioning in their homes, the department uses an array of measures to keep inmates safe. … Everyone has access to ice and water. Fans are strategically placed in facilities to move the air. Inmates have access to a fan and they can access air conditioned respite areas when needed.”

But people who are incarcerated can’t go to local cooling centers for hours at a time, as private citizens can, or stay temporarily with friends or rent hotel rooms during heat waves. They are completely reliant on prison staff to ensure that they have access to those resources.

In my view, without investments in cooling, preventing heat illnesses and deaths in prisons will become increasingly challenging as exposure to extreme temperatures becomes more common with climate change. Heat waves threaten everyone, but as long as prison temperatures remain unregulated and prisons lack enough cooling resources, incarcerated people will be at extreme risk.