This is a transcript of episode 7 of The Conversation Weekly podcast, COVID-19 caused the biggest drop in carbon emissions ever – how can we make it last? In this episode, we investigate the effect coronavirus lockdowns had on global carbon emissions and ask what this means for the fight against climate change as governments turn their focus on the recovery. And we hear how the pandemic exacerbated the hardships faced by migrant workers in Canada.

NOTE: Transcripts may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Gemma Ware: Hello and welcome to The Conversation Weekly.

Dan Merino: After the world pretty much stayed home for a year, there’s been an unprecedented drop in global carbon dioxide emissions.

Corinne Le Quéré: We estimate about 7% drop in emissions … this is the biggest we’ve ever seen.

Dan: In this episode, we drill down to find out what actually caused the reduction – and what this means for the fight against climate change as the world starts to recover.

Gemma: And we’ll be talking to Vinita Srivastava from The Conversation in Toronto, who’s host of Don’t Call Me Resilient, a new podcast about race. We’ve got an extract from a conversation that she had on the hardships faced by migrant workers in Canada during the pandemic.

Min Sook Lee: Workers living 20, 30 in a garage that has no windows and is used to store farm equipment.

Gemma: From The Conversation, I’m Gemma Ware in London.

Dan: And I’m Dan Merino in San Francisco and you’re listening to The Conversation Weekly, the world explained by experts.

Gemma: Dan, so I’ve really enjoyed how quiet the skies have been during the lockdown here in London. I live under a flight path so it can get pretty noisy, but the aeroplanes have been thankfully few and far between in recent months.

Dan: It’s been kind of similar here in the US, air travel dropped 60% last year, back to a level almost like in 1984 apparently. And car traffic was almost down to zero.

Gemma: Yeah in London too, at least at the start of the pandemic, there were fewer cars on the roads.

So Dan, I’d assume that this would all be good news for the environment, right? Fewer flights, fewer people driving, just means less CO₂.

Dan: It’s totally good news. Total global carbon emissions were down 7% last year … but that drop didn’t really last. I don’t know about you Gemma but traffic’s certainly back where I am. So I wanted to put last year into some perspective. How does it compare with what’s been happening in the past few decades? I spoke to two academics, one who looked at the pandemic’s effect on emissions and a second who studies whether our individual actions affect those around us when it comes to climate change.

Corinne: My name is Corinne Le Quéré. I’m a scientist, I’m a professor of climate change science at the University of East Anglia in the UK.

Dan: Corinne recently co-authored a paper comparing carbon dixoide emissions from fossil fuels from before the pandemic, to emissions levels during the pandemic.

Corinne: We looked at the global emissions, so from burning fossil fuel, mostly. And before the pandemic, these emissions were on the rise. So these emissions are the main cause of climate change and they were rising quite continuously. But in the last decade, the rise, the growth in emissions had been a lot slower than it had been before in previous decades.

Read more: We've made progress to curb global emissions. But it's a fraction of what's needed

Dan: But with no one driving, no one flying, and global economies put more or less on hold, countries around the world saw an unprecedented drop in their emissions

Corinne: In the countries that went under lockdown, the US, most of Europe, Japan, and India as well, at the height of the lockdown they were cut by about 30%. So we could see that there was the maximum effect about in April when most of the countries had their lockdown at the same time.

Dan: Since then, emissions have gradually crept back up. Economies have adapted to the pandemic and countries have eased some of their COVID restrictions.

Corinne: The effect of the lockdown is still keeping emissions at bay, but it’s much less now, of course, both because there are a lot fewer countries under lockdown. But also because the lockdowns are a lot looser as we learn what it is that we can and cannot do to limit the effects of the pandemic.

Dan: Taken as a whole, the year 2020 saw fewer emissions than 2019. In fact, it was the biggest global drop in modern history.

Corinne: We estimate about 7% drop in emissions. I mean, in terms of absolute number of billion tonnes, this is the biggest we’ve ever seen: 2.6 billion tonnes of CO₂. It still means we’re emitting 34 billion tonnes of CO₂ – so actually everything’s relative, isn’t it?

Dan: Ok, lets put this wild year into some context: Since 1990 global emissions have risen by 61%. But the pace of this growth has actually slowed down. Many of the most polluting countries have increasingly taken steps to limit their carbon dioxide output, such as shifting from coal to renewable energy.

Corinne: In the last decade, the rise, the growth in emissions had been a lot slower than it had been before in previous decades. You can see that there was effects of the Paris agreement or maybe more broadly energy policies and climate policies that had been put in place in response to climate change in the past years and even a decade or two. There’s over 2,000 climate policies around the world and we all starting to see the benefits of that.

Dan: The 2016 Paris Agreement is a legally binding, international treaty that sets out a roadmap for countries to cut their carbon emissions and implement greener policies. It’s been criticised as being too flexible and lacking enforceability, but supporters say it’s needed to prevent global temperatures from going above 1.5°C-2°C above pre-industrial levels, or, in other words, to prevent a climate catastrophe.

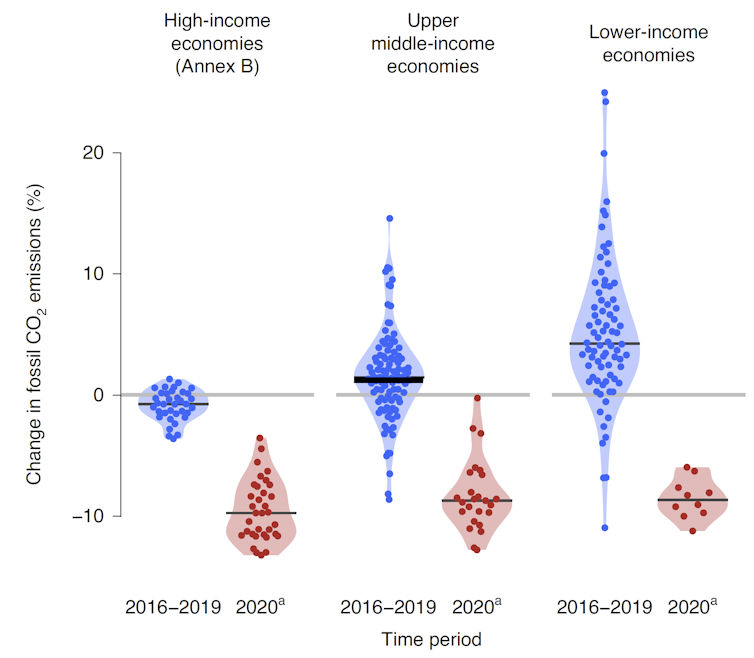

Corinne and her colleagues have been tracking fossil fuel emissions in more than 200 countries through time. Between 2016 and 2019, the years before the pandemic, they reported that 64 countries had actually reduced their CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels. But emissions had been rising in 150 countries, so the vast majority.

Corinne: At the moment, the wealthy countries, there’s 36 of them defined by the United Nations that keep track of these things. Of the 36 countries, 25 have their emissions actually decreasing. So you see them going the other way around, which is good, which is what you need to tackle climate change.

Dan: Good performers included the UK, Denmark and Japan, for example. But while some wealthy countries are reducing emissions, others are continuing in the wrong direction. Emissions from Australia, Russia, Canada and New Zealand are still increasing due to oil and natural gas use. So even though most of the 36 wealthy countries reduced emissions, taken as a whole, the group still is responsible for a tonne of emissions globally: 35% in 2019. For now at least, wealth and emissions go hand in hand.

OK, that’s the rich countries – but what about the rest of the world? When Corrine’s team looked at the emissions from 99 upper-middle income countries, in the five years before the pandemic, they found 30 of them were also reducing their emissions – among them Mexico, Singapore and Israel. But for the rest of these these middle-income countries, it was a mixed bag. China – which is classified as an upper-midldle income country – saw its emissions increase slightly, though much slower than the previous two decades.

Corinne: So 99 countries there, responsible for half the world’s emissions, and before the pandemic their emissions were still increasing as a group, but that’s the group that had really slowed down in the growth of their emissions.

Dan: Corinne said that some of these upper-middle income countries have started to pass greener policies in line with the Paris Agreement.

Corinne: Lots of countries have put policies in place. Think about Mexico, Indonesia. But also because prices have come down for renewable energy in particular, and these are starting to push heavy industry, fossil industry out.

Dan: As for lower-income countries – there are 79 of them – they accounted for just 14% of global fossil fuel emissions in 2019. If you want to explore this data more closely, compare countries over time, see the effect of the pandemic on individual countries, Corinne and her colleagues put together a fantastic interactive graphic that is in the show notes.

So the pandemic has shown that it’s actually possible to drastically reduce carbon emissions. We certainly don’t want to do it the way we did in 2020: shutting down economies and essentially banning travel, no one wants to relive that. But when thinking about ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, an inevitable question is this: what can I, an individual do? This question on the role of individual actions in the fight against climate change is something that’s preoccupying another researcher I spoke to, Steve Westlake.

Steve Westlake: I’m researching for a PhD at Cardiff University and it’s into ideas of leadership and leading by example when it comes to pro-environmental behaviour and particularly around climate change and high-carbon behaviours.

Dan: Steve told me that a few years ago, one of his mentors completely stopped flying for environmental reasons. This had a huge influence on Steve’s own thinking and behaviour, and for his PhD, he started studying that effect.

Steve: I surveyed people who knew somebody who’d given up flying, and it split people into two groups. And I found that those people who knew, knew someone who had given up flying, about 75% of them said it changed their attitudes in some way.

Dan: This ripple effect – one person’s decision expanding out to those they know - is pretty strong. When people saw someone else make a change, it influenced their own behaviour.

Steve: So it raised the importance of climate change, or it made connections between individual behaviour and climate change, or it raised the urgency. So yeah, about three quarters said it had changed their attitudes and about 50% said that they were flying less. So they’re not necessarily stopped altogether, but it had impacted their behaviour.

Dan: The effect is even more pronounced if someone you respect or admire changes their behaviour.

Steve: It’s kind of called the messenger effect in psychology. So it depends who is giving the message, and if it’s somebody who’s has some legitimate authority in your eyes, then you’re more likely to be influenced by them. You look at people who’ve symbolically acted and made a very strong case for social change.

Dan: Leading by example: unanimous support among climate researchers that this is a good thing, right? Well, some people argue that the climate outreach should not focus on individual people, who can really only do so much on their own. The thinking is that this takes pressure off of corporations, government and industry that could make really impactful systemic changes, almost unilaterally.

Steve: So there is a quite a strong narrative that says we shouldn’t focus on individual behaviour. And I understand that. However, my view is that the urgency is so important that we have to face down the difficulties. I don’t think we can try to get a cozy, warm consensus all the time in the way we’re communicating. But I think there does need to be this discussion about individual behaviour, because otherwise it’s sort of carte blanche for everything, which is kind of the way it is now. It’s sort of, it’s all about the system. And for me, the system won’t change without individual change. These two things go hand in hand.

Dan: Steve’s work shows that that individual actions have a strong influence on the people around you, so while your personal changes might be small, in total, they can add up to a huge amount, especially considering how much of total emissions are tied to a person’s daily life.

Steve: 65% of global emissions can be attributed to households. So a large chunk. Now that’s not to say all of those emissions are things you could choose to cut because obviously a lot of them are things you don’t have a lot of choice about, but it’s a big chunk of emissions, which is associated with people and their consumption.

Dan: Corinne Le Quéré’s work exploring the pandemic dip in CO₂ emissions really illustrates this. Her team found that much of the drop in 2020 can be linked back to cumulative individual actions.

Corinne: We saw really big changes in emissions during the confinement. So it’s important to say it’s not the pandemic, it’s not the disease itself that causes emissions, but the measures to respond to the pandemic have led to people like us not moving very much. Those who could, working from home.

Dan: The biggest single cause of reductions was from people not driving.

Corinne: So it’s road transport that accounted about 40% of the dip, there of the order of 30, maybe more percent of the emissions in the US and in Europe where the lockdown was particularly intense. And so not having so many people on the road made a huge difference.

Dan: Driving wasn’t the only thing of course.

Corinne: And then you had the consumption. So we consumed a lot less.

Dan: Nobody was eating out, clothing sales were way down, as were sales of electronics like phones and stuff.

Corinne: And therefore the industry wasn’t working so much, and that also accounted for a big chunk.

Dan: And to a lesser degree, even electricity use was down.

Corinne: It was less of a big contribution because although, we didn’t go to work, there’s more electricity use then in buildings at home, so it was more like a displacement of the energy use in the pattern.

Dan: So what about flying, which was almost completely halted during lockdowns? Well, flying certainly isn’t good for environment. If I were to take round trip flight from here in San Francisco to go visit Gemma in London, that would emit the equivalent of around 5 tonnes of CO₂ per person on the plane. That’s more than twice the emissions produced by a family car in one year. So you’d think that the global slump in passenger flights would have a big effect on emissions. But Corinne’s data paints a different picture a little bit.

Corinne: The interesting one is aviation. Aviation was the most hit by the crisis. So, I mean, it was cut by three quarters. So 75% cut in aviation in the number of flights taking off in countries that were under lockdown. But on a normal year, aviation is only 3% of global emissions. So even if you cut this by three quarters, only you’ve cut by 2%. It wasn’t that big a deal globally.

Dan: So I asked Corinne what she thought we should be doing to put the breaks on climate change.

Corinee: We don’t actually think about this so much, but driving is a lot more polluting than aviation. I mean, the thing is that aviation per mile travel is a lot worse than driving, but we drive a lot more. And so also many countries don’t fly at all. So, relatively speaking, if we can sort out the car transport, we can do a very big difference to global emissions.

Dan: She says that to stop the planet from surpassing the 1.5°C-2°C limit set by the Paris Agreement, a lot more needs to be done than just individual changes. Remember, in the years before the pandemic hit, 64 countries had already been reducing their emissions, but those emission reductions weren’t even close to what is needed globally.

Corinne: If you look at the countries that had their emissions decreasing before the pandemic, in just those countries, then the cuts in emissions were about 10% of what is needed year on year to tackle climate change. Now, there was 150 countries that increased their emissions at the same time. So we’re a long way from where we want to be.

Dan: On top of that, experts have warned that even if countries did reach their Paris emissions goals by 2030, the world would still warm by almost 3°C. This could cause unimaginable harm to people and animals across the globe. And lest we forget, the biggest polluting countries will almost certainly suffer the least, while poorer countries take the brunt of the climate catastrophe.

But Corinne stressed that COVID-19 showed what governments and collective action can do. Huge societal changes to reduce emissions happened.

Corinne: So the pandemic cut emissions by 2.6 billion tonnes of CO₂. And what we need is 1-2 billion tonnes of CO₂. So it’s big, but we did more in the pandemic with all the wrong reasons, but size wise, you can see with these numbers that to tackle climate change, you need large-scale actions. You need people involved. You need to have something that is coordinated, that governments and society wants to do, to move forward.

Dan: But as countries slowly climb out of the pandemic and governments inject piles of money into their economies. There’s a danger that green measures will take a backseat to the status quo.

Corinne: Among the economic stimulus packages around the world, I would say there’s two handfuls, maybe 10, that are more green than not. So green means that they invest in what’s needed, but there’s a big basket of economic stimulus packages that are very, very brown that invests in infrastructure that will really lock us into high emissions and high climate change.

The economy has simply restarted in many countries and China in particular, which was less hit by the pandemic than other countries for less long a lockdown, and also much earlier in the year. So they were on under lock down in January and the first half of February and then they’ve had since February the time to reboost their economy somewhere.

Dan: But Corinne says it’s not too late. A lot of the recovery money is going to immediate rescue measures to help people survive this crisis. But a lot of money also is going to future investment in infrastructure too.

Corinne: If they can now be pushed into renewable energy, pushed into renovating homes for energy efficiency, electrifying transport, cars. They can be done still now. So I would say, the opportunities are not set yet. And this is what we’ve been trying to say in our paper: the actions we do now, they will make a difference. It’s not all done, and then we’ll say, “Oh, well, let’s wait for the next opportunities.” What we do now is really super critical.

Gemma: For somebody who spends their time researching global carbon emissions, Corinne is actually refreshingly positive.

Dan: Yeah, it’s not all lost quite yet. The choices our governments make really matter, particularly as we choose a recovery path from the pandemic. You can read more about the recent study that Corinne Le Quéré and her colleagues published, in an article on The Conversation. Find a link in the show notes.

Gemma: Coming up, we’re going to be joined by Vinita Srivastava from The Conversation in Toronto to talk about racism against Canada’s migrant agricultural workers. But first, we’ve got a message from Wale Fatade, commissioning editor at The Conversation in Lagos, Nigeria, with some recommended reading.

Wale: Hi, I’m Wale Fatade, a commissioning editor in Lagos, Nigeria. These are two stories that caught my attention in the last week. The first is an article by Benjamin Maiangwa, a teaching fellow in international relations and peace and conflict studies, in Durham University in England and Chigbo Anyaduba, an assistant professor at the University of Winnipeg, Canada.

The authors argue that while it’s over 50 years that the Biafran War, a civil war in the Eastern part of Nigeria ended, issues surrounding the end war have not been fully addressed. And they spoke about memory practice, which is a way of remembering the past, not being enough to remedy the injustice associated with the war. They say that this is a merely symbolic exercise that failed to confront a violent system. And they conclude by saying that what needs to happen is some form of political justice to confront the pre-conditions of the war. And I’m sure you will find it fascinating, in the sense that even though the Biafran war ended in 1970, it still dominates our political discourse in Nigeria to date.

My second recommendation is a review of some recent research on beer in Namibia written by Paul Nugent, University of Edinburgh, Scotland. He writes on why beer remains a marker of identities, and also why the brewing industry remains a source of national pride in Namibia. And the article also affirms how the escalation of liberation wars across southern Africa had an important impact on the beer industry. So that’s it from me, happy reading.

Dan: Wale Fatade there with The Conversation in Nigeria.

Gemma: So now we’re joined from Toronto by Vinita Srivastava host of another new podcast from The Conversation. Hello, Vinita.

Vinita: Hi Gemma.

Dan: And hello, Vinita, welcome.

Vinita: Thanks for having me.

Gemma: So Vinita, tell us about your podcast, Don’t Call Me Resilient.

Vinita: So Don’t Call Me Resilient, on the pod we take a deep dive, looking at how current issues are intersecting with race and racism. And we have these really insightful conversations with scholars and with activists who view the world through an anti-racist lens. But not only that, our guests are also intimately connected to the work that they’re talking about.

Gemma: They are, and it really comes through in the show. I’ve been really enjoying it. But can you explain why is it called Don’t Call Me Resilient?

Vinita: Yeah. That’s the big question. What’s actually wrong with calling people resilient? Isn’t it a nice thing when you say “Oh, you’re so resilient”? And of course we do, we want to celebrate our human resilience, our ability to adjust and get over all of these difficult conditions being thrown at us.

But for so many people, especially black, indigenous, poor, racialised people, being labelled resilient, especially by politicians has other implications. So it means that we’re often asking people to, you know, pick themselves up by the bootstraps. Or, you know, we’re leaning into these dangerous biases of strong communities instead of looking for the systemic solutions that we need.

Gemma: And thanks very much for letting us use one of your interviews on our show, today Vinita. We’re going to hear an extract from a conversation that you had about migrant workers in Canada. So can you introduce it for us?

Vinita: Sure, sure. In this episode, OCAD university professor Min Sook Lee shares some of what she has learned in the past 20 years while making documentaries about migrant workers in Canada. And she calls the workers “the unseen”. She explains that both policy and social attitudes are designed to keep migrant workers invisible, but their unsafe working conditions reached a red alert situation after COVID-19.

Vinita: Min Sook, I have so much I want to ask you, and so I’m going to just jump right in. What were some of your first thoughts when COVID-19 first hit?

Min Sook: When the lockdown was declared and we witnessed all around us the alarm of the global pandemic and the very first thing I heard was social distancing — that what would protect you from COVID-19 was social distancing. And immediately I knew migrant workers would be in trouble because migrant workers do not have control of their own space. Social distancing is a luxury. It means you can control the space that you live and work in. And migrant workers are regularly housed in very crowded living conditions. Oftentimes I have seen workers living 20, 30 in a garage that has no windows and is used to store farm equipment when workers are not living in the garage, with one or two bathrooms that are accessible.

I have also seen that migrant workers work very close, cheek to cheek, elbow to elbow in the greenhouse spaces and factory lines when they’re processing foods, fruits or cutting fish. So I knew that the pandemic, which was sending alarm bells across the world, what was required to protect yourself from the pandemic – social distancing – would be unavailable and inaccessible to migrant workers because they are required to work very closely to each other, number one. But even more concerningly, they often are housed in living conditions that are very crowded and they can’t control the spaces that they live and work in because of the laws of Canada’s migrant worker program.

Vinita: Are you in touch with some of the folks that you have interviewed over the years? Do you continue to hear from them?

Min Sook: Yes, and I’m not going to name names because workers often need to have their identities protected. There were two workers out on the west coast. They were sent back by their employer because they were in communication with community organisers in the west coast working on a farm. And they agreed to receive some food and support because community organisers saw that migrant workers were — ordinarily migrant workers are very isolated. They are kept away from the non-migrant worker population. And oftentimes employers ensure that migrant workers do not have very much contact with Canadians.

So it’s a kind of isolation that I think most Canadians could not imagine. Where what I have seen is that a migrant worker would arrive in the airport, let’s say, on a 4:00am flight from Mexico or from the Caribbean. They’ll be picked up by a broker or someone who works in the farm, maybe the employer or supervisor, driven to their living quarters and the next morning they’re expected to show up at work. And then it’s seven days a week of work, and oftentimes where they’re working on farms, which are really isolated and rural communities, and getting access to go grocery shopping, to do some banking or to do any kind of activity outside of work, is monitored and requires transportation from the employer, and it requires that kind of organisation. So the isolation of migrant workers is extreme.

And in the west coast, when COVID hit, there were workers who were concerned about the quarantine measures that were being applied to them, required of them, and their employer immediately put down measures such as no guest visitors, no leaving premises after a certain set number of hours. And then the workers were also not able to go shopping during the quarantine time or if they were ill. And the food that they were being provided was not adequate. And so they were community organisers that delivered food to the workers. And once the employer found out, the employer sent those two workers back to Mexico because the employer decided that they had contravened the rules of the farm. So workers being punished for speaking out is a frequent occurrence.

Vinita: Social distancing, and for a while when we were in lockdown, stay home. What I’m hearing you say is that home is not home. It’s a very dangerous place. It’s overcrowded and there’s no distance.

Min Sook: We couldn’t feed Canadians without the labour of migrant workers. Many people think we’re talking about family farms with a few chickens and pigs and cows and three generations of farmers working hard out in the sun. That’s not the picture of industrial agriculture or factory farming that’s underway in Canada that produces most of the food that we eat. We’re looking at greenhouses that are 10 football fields in length. These are massive industrial operations and there are hundreds of workers working in these greenhouse operations.

There have been billions of profits made through this industry on the backs of migrant workers who are unfree. They can’t change their employer, they can’t change their job site. And most workers are in Canada without a pathway to citizenship, without a pathway to permanent residency, without a pathway to status.

Vinita: Why do you think that pathway is blocked?

Min sook: You know, the restricted pathways to citizenship are designed. They’re designed to keep Canada looking the way it does and primarily keeping, the majority of workers who come into Canada under the migrant worker program come from the global south. Most of the workers are racialised workers, most workers come to do the jobs most Canadians don’t want to do. The 3D jobs: dirty, difficult and dangerous.

You could say that the picture of Canada as this rosy postcard of Canada as a country that invites diversity from people all over the world. And the doorways are open and the opportunity’s here knock and we’ll invite you in. Well, the reality we know is that the front doors to Canada are blocked. There are long waiting lists and increasingly there are more and more onerous restrictions on immigration pathways to Canada. The back door is wide open for temporary migrant workers to do the essential work that industries need, but that back door ensures that you will remain permanently non-status. So you’re not here under a temporary foreign worker program as a temporary worker because your labour is only needed on a temporary basis.

Vinita: How much of these attitudes and policies have to do with race, the fact that these are black and brown bodies doing the work and the labour?

Min Sook: Oh, yes, this is a racist program, undoubtedly. Without a doubt. How is this program designed? I think we have to recognise the history of a program like this began with the settlement of Canada. The colonial history of Canada is very much aligned to and part of the creation of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program.

So, back from the 1800s, when Canada had to build railroads to connect towns dotted across the landscape, the people that they needed to build the railroads, the labour that was required, Canada set up a migrant worker program to bring in Chinese workers to do the work on the railways. Chinese workers who would do the work for less pay than white workers and do the most dangerous tracts of work using dynamite in the Rockies, for example. So the programs that were set up in the 1800s to bring Chinese workers in were designed to extract labour, but also to deter settlement. They were allowed on a certain period of time and then they were expected to go, never expected to settle.

Vinita: You’ve been doing this for a while. You’ve been documenting migrant workers long before COVID, have you seen any dramatic changes in their conditions or any improvement or dramatic changes for the worse?

Min Sook: No, I think that things have gotten actually even more strikingly concerning. And the idea that workers are unseen, that is deliberate. There’s a constructed way workers are unseen. I’d like to offer that as a thought around the history of migrant worker programs and how racist they are.

Vinita: Thank you so much for all your time today. I really appreciate it.

Min Sook: Thank you for having me, Vinita.

You can listen to Vinita’s full interview with Min Sook Lee on episode 4 of Don’t Call Me Resilient.

Gemma: Thanks so much Vinita. We should say that Canada isn’t unique in the way it treats its migrant workers, and the racism involved in these temporary programmes.

Vinita: I mean there’s a great story this week on our site about workers in south-east Asia and the similar circumstances of racism that they experience along with the crowded living conditions, and these are in countries like Singapore and Thailand. This is a system that exists everywhere and, you know, people are always surprised when we talk about racism and we think “What the Thai are racisitic towards the Burmese?” Of course they are, because they’re migrant and they face the same xenophobia and racism that migrant workers in Canada face.

Dan: OK Vinita, where can people go to listen to the podcast?

Vinita: I would ask people to please go search for Don’t Call Me Resilient, wherever you get your podcasts.

Dan: We’ve also got a link in the show notes.

Gemma: OK, that’s it for this week. You can find links to all the expert analysis we’ve mentioned in this episode – and more – in our episode notes. Where you can also find a link to sign up to The Conversation’s free daily email. And if you want to reach out – tell us what you think about the show or what questions we should be asking academics, find us on Twitter @TC_Audio or on Instagram at theconversation.com. Or you can email us on podcast@theconversation.com.

Dan: Thanks to all the academics who’ve spoken to us for this episode. And thanks too to Conversation editors Anthea Batsakis, Sunanda Creagh, Will de Freitas, Wale Fatade and Stephen Khan. And of course, Vinita. Vinita is there anyone else you’d like to thank from the team at Don’t Call Me Resilient?

Vinita: Oh the Don’t Call Me Resilient team is an amazing, passionate group of people, so I have to thank them. Reza Dahya our sound guru and Nahid Buie and Ibrahim Daair our producers.

Gemma: Great, thanks. This episode of The Conversation Weekly is co-produced by Mend Mariwany and me, with our sound design by Eloise Stevens. Our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

Gemma: Thanks for listening everybody. Until next time.