If there is a single image that explains the success of Lynton Crosby’s campaign strategy for the British Conservative Party, it is the leaflet handed out in the last week of the general election campaign in the seaside townships of Kent – specifically, in the seat of Thanet South, which the Tories were trying to win back from UKIP leader Nigel Farage. The Conservative government’s re-election – through wins in Thanet South and across England – is the latest and perhaps most startling electoral triumph for Crosby, the Australian strategist who is arguably this country’s biggest political export since the secret ballot.

The leaflet did not mention the local Conservative candidate, the Conservative prime minister or the Conservative Party. It did not even appeal to Conservative voters. Instead, it made its pitch to UKIP voters, and it did so by demonising the Labour Party and – perhaps bizarrely in a town much closer to Paris than Edinburgh – the Scottish National Party (SNP).

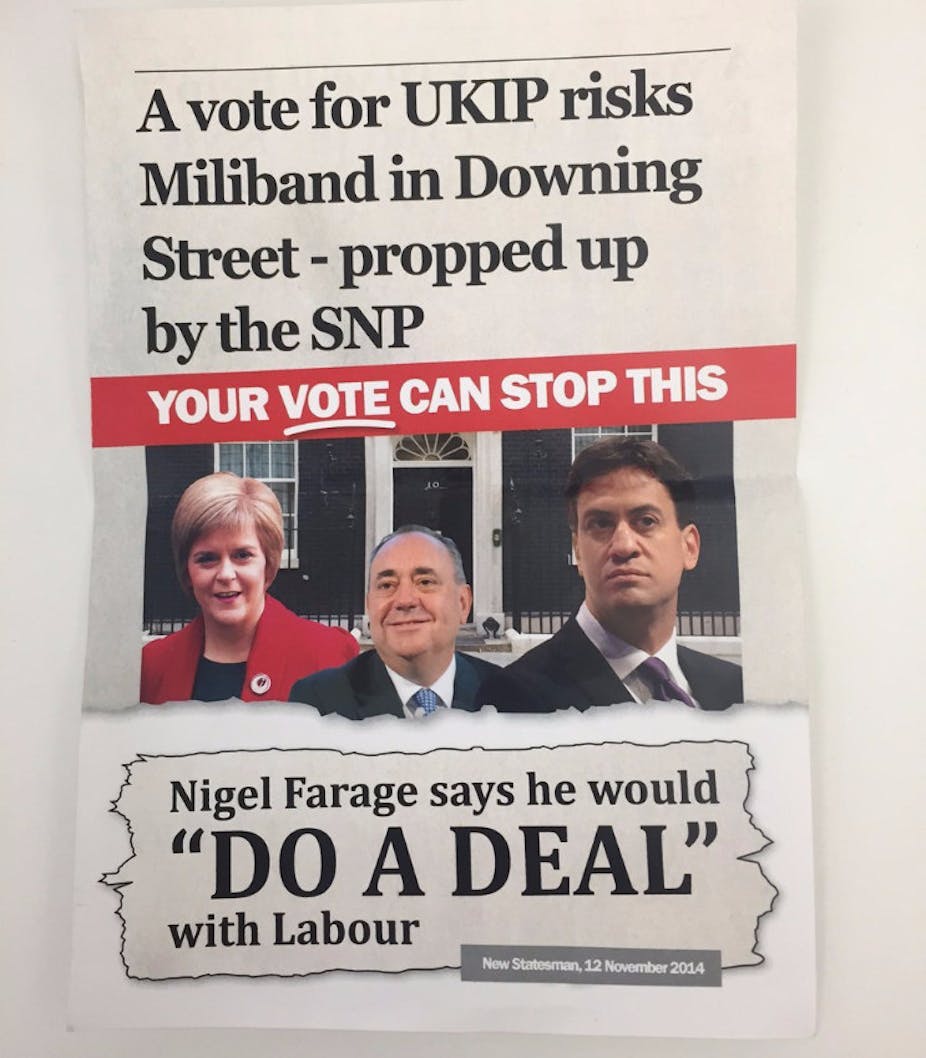

Above a simply photoshopped image of Labour leader Ed Miliband plus the two SNP leaders Nicola Sturgeon and Alex Salmond outside Number 10 Downing Street, the leaflet claims:

A vote for UKIP risks Miliband in Downing Street – propped up by the SNP.

Your vote can stop this. Nigel Farage says he would ‘do a deal’ with Labour.“

Decoded, the message is: only the Conservatives can deliver stability in England; every other party delivers deal-making and chaos.

It’s unlikely Crosby personally signed off on this leaflet – though given his notorious centralisation of campaign authority, that is not to be ruled out. What is much clearer in the election post-mortems is that its message - truthful enough, relevant, low production values but penetrating, and efficiently killing three birds with one stone - perfectly exemplified Crosby’s overall strategic intent for the Conservatives.

In England’s complex multi-party electoral landscape, Crosby’s strategy was to reduce the voting choice to a simple binary "us” versus “them”, positioning the Conservatives alone as representing stability against Labour, the SNP, UKIP and even their own erstwhile coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats.

The Conservatives did not create SNP popularity or Lib Dem unpopularity, but they exploited both effectively, portraying Labour as hopelessly compromised by its need to “do a deal”. In a separate Tory poster Miliband was shown as a tiny figure literally inside Alex Salmond’s pocket.

The rise to back-room power player

Adelaide-born in 1956, Crosby was an active Liberal Party member as a teenager and ran unsuccessfully for former Labor premier Don Dunstan’s seat of Norwood in 1982. Deciding to pursue a career in the Liberal back-rooms instead, he became a parliamentary staffer before specialising in election campaign management in Adelaide, then in Brisbane as Liberal state director, and finally in the national head office under then federal director Andrew Robb.

Crosby was deputy director of the campaign that delivered John Howard to The Lodge in 1996. He directed Howard’s re-election campaigns in 1998 and 2001 before resigning to set up a consultancy with market researcher Mark Textor.

The consultancy provides political advice to business and conservative parties in Canada and New Zealand, as well as the Australian Liberal Party and the British Conservatives. Boris Johnson, twice elected mayor of London after Crosby Textor campaigns, has described Crosby with typical extravagance as:

simply the best campaign manager and political strategist I have ever encountered or even heard of.

Many in Westminster, on both sides of politics, now agree. Crosby has said repeatedly that election campaigns are fundamentally about identifying the voters – who they are, where they are, what matters to them, and how you can reach them – who will deliver your party a winning majority of seats in parliament. Thus the hallmarks of a Crosby political strategy include ruthless centralisation of campaign authority, long-term development of research-based campaign strategies, and disciplined targeting of resources.

That much is of course true of virtually any winning campaign by a political party in contemporary democracies. Campaign professionalism is highly mobile across boundaries of nation and party. Crosby’s success, then, lies in his ability to apply those abstract professional hallmarks to the particular requirements of his campaign client in the here and now.

Campaigning in Australia is not the same as campaigning in the United Kingdom. Campaigning for a challenger (Howard in 1996, Johnson in 2008) is not the same as for an incumbent (Howard in 1998 and 2001, David Cameron in 2015). Campaigning in the media environment of Brisbane City Council in 1994 is a far cry from contemporary social media and Big Data campaigning.

Crosby’s four elements of success

In this context it seems Crosby’s campaign had four elements that worked particularly effectively for the Conservatives.

First, as always, Crosby insisted on a centralised campaign structure. He held ultimate authority for strategy including message development.

Second, he had a long-term plan for re-election, based on Textor research. Crosby held his nerve while many around him fretted about the apparently immobile published polls.

Third, he targeted winnable seats – abandoning Scotland and much of London but crushing Labour in marginal seats and the Lib Dems in their heartland.

Fourth, as the Thanet South leaflet exemplifies, he targeted persuadable voters in those seats, with a precise cut-through. Crosby has often said that effective campaign messaging is about framing the choice: not just saying something you think voters might like to hear, but sharply defining yourself in contrast to your opponent, and doing so with evidence. This is what the Thanet South leaflet does so effectively.

A new element in the Conservative campaign, however, reflects an unexpected development. For the first time in his career, Crosby reached across the political divide to import talent from the US Democratic Party, in the person of heavyweight Obama strategist Jim Messina. This appears to be recognition that the Conservatives, like the US Republicans and the Australian Liberals, have been weaker than their opponents in the emerging battleground of data-driven campaigns.

The British Labour Party had reportedly made a big investment in this kind of ground war – but in vain.