Denis Norden, who died recently aged 96, epitomised a peculiarly British brand of comedy that emerged from a specific time and place. For some years after the end of World War II, while many young people were still being called up for National Service, a generation of talented actors, musicians and comics who had cut their teeth entertaining the troops, were finding their way onto the stage and the airwaves.

Norden, who spent the war as a radio operator, emerged from the RAF as one of the new breed of entertainers who had worked for the gang shows, concert parties, Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) and Combined Services Entertainment (CSE) agencies that brought live shows to the troops. Their job was to provide light relief from immediate circumstances – remind their uniformed audience of home while encouraging the maintenance of a cheery Blitz spirit on the Home Front. Keep calm and carry on was the message.

Men overwhelmingly supplied the comedy for their peers. Female entertainers tended to be established singing stars such as Gracie Fields or “forces sweetheart” cast types like Vera Lynn. The relative lack of female comics meanwhile allowed for an overabundance of men donning drag for comic purposes.

The comedians concentrated on the small, silly and local. Jokes were parochial and daft in tone rather than overtly satirical. The comic voice was political only in so far as it reinforced class hierarchies and social conventions that mirrored services life at the time. Above all, the humour was unashamedly escapist.

After demobilisation, Norden – like many of his contemporaries from services entertainment – went on to dominate the comedy and media industries – bringing the same values and mode of expression to their live, radio, TV and film production work after the war. Former sergeants Cardew Robinson and Charlie Chester, for example, found success on the radio, while sergeant Frankie Howerd would go on to work across the media.

Leading aircraftman Dick Emery would eventually become the top TV character comedian of the 1970’s, complete with his pre-Little Britain cross dressing and catchphrases, including the famous: “Ooh you are awful … but I like you.” The generation that entertained the troops continued to make popular comedy as a form of escapism. Norden’s style of presentation, in particular, encapsulated the air of almost throwaway insouciance and stiff upper lip approach that prevailed after the war.

From horror to humour

Indeed, in the light of how little war experiences were directly to affect British Forces comedians’ creativity, it is extraordinary to think of the following parallel events. In 1945, the Italian Jewish writer Primo Levi was liberated from Auschwitz concentration camp. Levi went on to produce the memoir If This is a Man – a devastating account of man’s inhumanity to man.

In the same year, Norden – himself Jewish – along with fellow future comedian Eric Sykes, visited the recently liberated Bergen-Belsen death camp. In stark contrast to Levi’s memoir of suffering, Norden would go on to write the script for “Balham, Gateway to the South” – a parody of a travel documentary that poked gentle fun at a London suburb.

Both Norden and Sykes – also demobbed from the RAF – would go on to produce some definitive British comedy of the post-World War II period. Norden achieved success as a writer and producer of such shows as BBC Radio’s Take It from Here (1948-1960) which featured the Glums, a resolutely working-class family complete with an array of reassuring catchphrases. Norden’s Balham sketch, incidentally, would later feature the vocal talents of fellow armed forces comedians Peter Sellers and Benny Hill, both of whom would become internationally renowned comedians. Sykes, meantime, would achieve fame in his eponymous domestic sitcoms.

Surreal escapism

The comic voice that continued from armed forces entertainment remained cosy and parochial, adopting the attitude of gentle stoicism of little men against the system. It achieved ultimate expression in the work of Tony Hancock. Hancock’s comic style illustrated the archetypal forces comic position of a pugnacious yet resigned persona with something of a make-do-and-mend attitude along with a mutually exclusive respect for – and suspicion of – class distinctions and hierarchies.

The permeation of the silly comedy strand was most evident in the humorous invention of The Goons. Lance bombardiers Harry Secombe and Spike Milligan, along with Peter Sellers, had been forces entertainers and their vein of local surrealism continued to send up British post-war characters in a gently subversive manner, but still using the default escapist tone.

It was not until considerably later that the broadcasting companies reflected more directly on the experiences of servicemen in shows including The Navy Lark (BBC: 1959-77) on radio or The Army Game (ITV: 1957-61) on television. Jimmy Perry and David Lloyd wrote directly about the concert party experience much later in It Ain’t Half Hot Mum (BBC: 1974-1981).

By 1971 Milligan had published his memoir Hitler, My Part in his Downfall. Still no Primo Levi-type text, this was a self-deprecating riff on comic failure with the war used more as a peg upon which to hang surrealist comic observations.

But then, it is understandable that any all-too real horrors were masked in the later comedy of this breed of entertainers. Future Carry On stalwarts, writer Talbot Rothwell and actor Peter Butterworth sang and joked to their fellow prisoners in Stalag Luft III to distract the guards from discovering escape tunnels being built. Future Goon Michael Bentine actually helped liberate Bergsen-Belsen (before Norden and Sykes arrived there).

Civil service of comedy

Small wonder, perhaps that these comics would turn to the comfort offered by simple silliness and choose escapism in its truest sense. In rechannelling their comic taste into another kind of “Civil Service of Comedy” after the war, the Forces’ comedians found fictitious outlets that were in contrast to their real experiences.

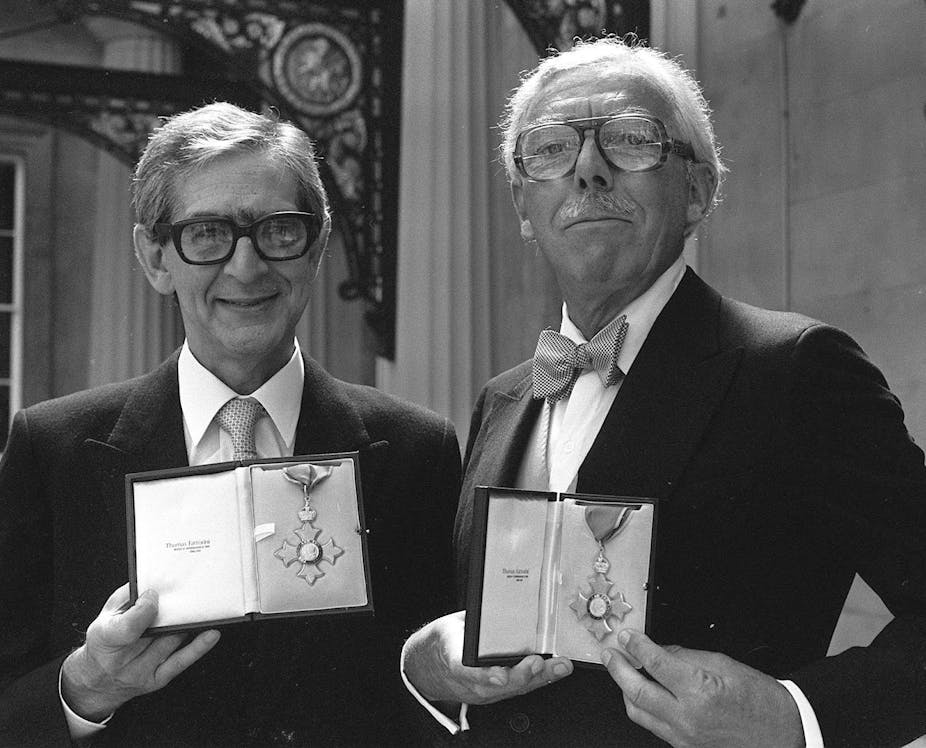

Norden would go on to become the elder statesmen of the bad pun. Like many of his contemporaries, he started to seem old-fashioned by the 1960s and was replaced, in his turn, by the new generation of university comics in the satire boom. Along with his writing partner Frank Muir, he moved increasingly into nostalgia gigs and other television-friendly formats which allowed for the forces’ comedic attitude of not taking anything too seriously.

In an extraordinary breeding ground of space and time, a very British sense of humour was forged. Perhaps the last of those gentleman-soldier comics whose like we shall not see again, Denis Norden, we salute you.