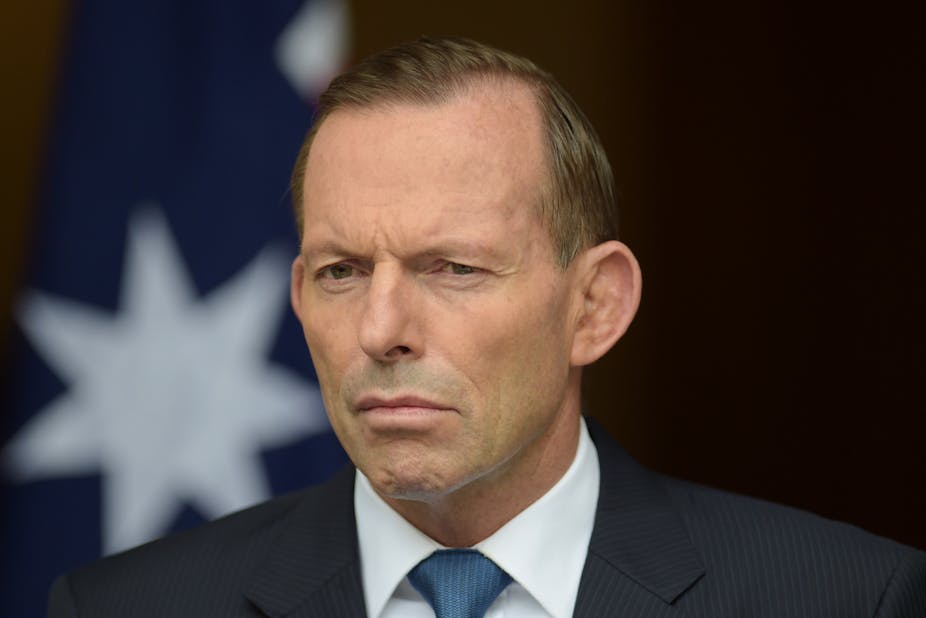

Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s claim this week that people living in remote communities were making a “lifestyle choice” that taxpayers shouldn’t be obliged to fund was not just the result of an unguarded moment. Rather, the phrase reveals an underlying view that social circumstances are the responsibility of individuals, rather than societies.

Commentators as well as Abbott’s top advisers on Indigenous affairs were quick to criticise the characterisation. Others suggested it was just another prime ministerial gaffe that shouldn’t distract us from the real issues.

Abbott is infamous for his gaffes and “dad jokes”, but this was not one of those moments. A day after he made the remark, the prime minister defended his use of the phrase on the Alan Jones Show.

Sounds familiar

For those of us who work in, or observe, public health, using a phrase like “lifestyle choice” to shift responsibility away from the government is familiar territory. For decades, the risk factors of chronic diseases such as heart disease or type-2 diabetes were described as the “diseases of lifestyle”, rooted in individual choice.

But chronic diseases actually have a plurality of causes that include genetics, environment, and social and economic circumstances as well as behaviour. To reduce them to individual choices misrepresents what we know about these complex diseases and places an unjustified burden of responsibility on individuals.

Still, it’s a useful device for cash-strapped governments. After all, if you alone are responsible for causing your illness, then you should also be responsible for its treatment. It provides governments with grounds for withdrawing all kinds of services.

Governments that emphasise “lifestyle choices” become free to ignore inconvenient facts such as the correlation between lower incomes and poorer health. They don’t need to ensure equitable access to health care or to regulate companies that produce tobacco, alcohol or food. Being unhealthy, or ill, is after all simply a “lifestyle choice” within the full control of individuals.

“Lifestyle choices” also appear in other public policy debates as a way of drawing attention to individual responsibility, while minimising the contribution of structural factors. “Lifestyle choices” suggest health, education and employment opportunities, for instance, are solely or primarily within the control of individuals, and that there is little role for the state to intervene.

They also indicate who is “in” and who is “out”. Certain lifestyle choices have been used to define national identity, by taking cultural practices to indicate those who belong. These can be banal choices, such as wearing thongs at the beach, eating Vegemite or drinking a certain brand of beer. But they can also have more insidious expression.

In proposing that the burqa and niqab should be banned in Australia, for instance, Pauline Hanson recently said:

This is Australia. If Muslims aren’t happy with our customs, they should find an Islamic country that accommodates their lifestyle choices and move there.

Who is responsible?

Beyond the clearly absurd idea that people in remote communities are making a “lifestyle choice” is the question of why our self-appointed “prime minister for aboriginal affairs” would choose this form of words in the first place.

As in the public health context, it may be for the convenient policy implications. Calling something a “lifestyle choice” makes everything that goes wrong the responsibility of individuals; rather than a failure to provide services or the result of social and historical circumstances, shortfalls become individual failure. A lifestyle choice is something from which both policy ambition and discretionary funding may at any time be withdrawn.

While referring to his government’s own “long-term, ambitious framework” for Closing the Gap in Indigenous disadvantage on the same day, Abbott warned:

if people choose to live where there’s no jobs, obviously it’s very, very difficult to close the gap.

This statement directly links the “lifestyle choice” of living in a remote community with the success or failure of efforts to close the gap. It shifts all the responsibility onto Indigenous people themselves, rather than government, which controls all the policy levers.

At first glance, this seems in stark contrast to Abbott’s speech in response to the Closing the Gap Report in early February, 2015. At the time, he said:

until Indigenous people fully participate in the life of our country, all of us are diminished.

But this week’s events may help us appreciate more fully what the prime minister meant. It may be that the prime minister believes Aboriginal people in remote communities are choosing not to participate in the nation’s life, and indeed being irresponsible in a manner that indicates their not belonging.

Since this is their “lifestyle choice”, neither the government nor the prime minister for aboriginal affairs can be held responsible.