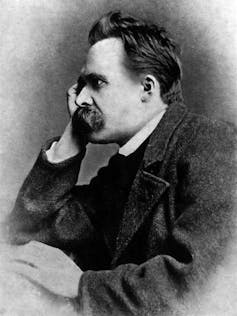

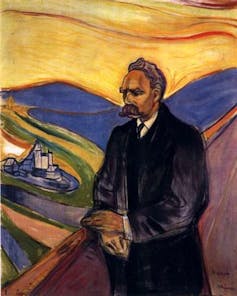

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) is sometimes dismissed as a malevolent figure, obsessed with the problem of nihilism and the “death of God”.

Understandably, these ideas are unsettling: few of us have the courage to confront the possibility our idols may be hollow and life has no inherent meaning.

But Nietzsche sees not only the dangers these ideas pose, but also the positive opportunities they present.

The beauty and severity of Nietzsche’s texts draw from his vision that we could move through nihilism to develop newly meaningful ways to be human.

Comfort and purpose through God

For centuries, the Bible gave people a way to value themselves and something to work towards.

“We all,” declares St. Paul, “with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another” (2 Corinthians 3:18).

The divine and the human meet in this description. Believers felt uplifted because they held God’s attention. God loved us (1 John 4:19) and saw us, down to our sinful foundations (Hebrews 4:13), yet his love persisted. This love enabled us to endure the pain of life. And because he saw us and our faults, we were encouraged to improve ourselves little by little and live up to his image.

For Nietzsche, the son of a Lutheran pastor, the growth of scientific understanding after the Age of Enlightenment had gradually made it impossible to maintain faith in God.

“God is dead”, Nietzche proclaimed.

Nietzsche saw the danger in this atheist worldview. If we weren’t suffering to get closer to God, what was the point of life? From whom now would we draw the strength to endure life’s difficulty? God was the origin of truth, justice, beauty, love – transcendental ideals we thought of ourselves as heroically defending, leading lives and dying deaths that had meaning and purpose. How could we play the hero to ourselves now?

The consequences of the death of God are horrific, but also freeing. In The Gay Science (first published in German in 1882), Nietzsche has the news of God’s death relayed by a man driven mad through fear at what a godless life might be like. Eventually, he breaks into churches to sing God’s requiem mass.

Without God, we are alone, exposed to a natural universe devoid of the comforting idea of a God-given purpose to things. According to Nietzsche, this state of nihilism – the idea that life has no meaning or value – cannot be avoided; we must go through it, as frightening and lonely as that will be.

A new dawn

For Nietzsche, nihilism can be a bridge to a new way of being. We are “undetermined animals”: malleable enough to be refashioned.

Our task now is to transform from the old Christian way of being human, towards what Nietzsche calls the Übermensch or “Overhuman”.

Christianity’s problem, in Nietzsche’s view, is that it slowly but surely destroys itself: ironically, prizing truthfulness as a virtue eventually leads to an intellectual honesty that rejects faith.

Our quest for honesty has given birth to a “passion of knowledge.” Now the search for answers to life’s hardest questions, and not the worship of God, is our greatest passion. We hunt for the most accurate reasons for our existence and likely find the answers in science rather than religion.

Nietzsche writes for those who are invigorated by questioning. Indeed, knowing and accepting that we are human and fallible – no longer charged with trying to reach a divine standard – leaves us lighter. As he writes in Daybreak, God’s “death” removes the threat of divine punishment, leaving us free again both to experiment with different ways to live and to make mistakes along the way. He wants us to seize this opportunity with both hands.

We can be the heroes of our own stories again, once we reclaim from God our creative wills. Nietzsche encourages us to treat our lives like the creation of works of art, learning from artists how to tolerate and even celebrate ourselves by cultivating “the art of looking at ourselves from a distance as heroes”.

Influence and relevance

Nietzsche continues to have an immense influence on philosophy and how we see our everyday struggles.

Many today will relate to his belief that we are living through a state of crisis, asking questions about the point of life in an age marked by affluence, image, and the damage wrought by religious fundamentalism.

By contrast, Nietzsche offers us a way toward meaning and purpose without the gruesome consequences of those who impose their religion on others, regardless of the cost.