It is bizarre that gas customers in Japan buy Australian gas more cheaply than Australians. Some of this gas is drilled in the Bass Strait, piped to Queensland, turned into liquid and shipped 6,700 kilometres to Japan … but the Japanese still pay less than Victorians.

When Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull meets gas industry bosses in Canberra tomorrow he will be regaled with tales of looming blackouts, spiralling prices and the stubborn refusal of state governments to open up coal seam gas fields to assuage the impending supply crisis.

Turnbull will be fervently advised to avoid a domestic reservation policy to earmark gas supplies for Australian consumers and businesses, though Western Australia has one. He will be implored not to tamper with the “market”.

There is no market though, only a cartel of six big players who control the price: Santos, Exxon, BHP, Origin, Arrow Energy and Shell. Markets have visible prices and quantities on the bid and offer. The cartel even hides information about its gas reserves from government.

As the price of gas has shot up threefold, as high prices exact a drag on the entire economy, and as the government confronts its challenge of energy security, it is worth considering the global gas glut.

Tonight, at the Columbia Law School in New York, Bruce Robertson, an analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), will hand down a paper describing how this gas glut will only get worse, and how excess supply and faltering demand are leading to a breakdown of the contract pricing mechanism.

Australia now exports 12% of the world’s gas. When the LNG export facilities are running at capacity, this country will be the world’s premier exporter.

Incidentally, Qatar, now the world’s biggest exporter with 32% of the market, raises three times as much in royalties as Australia for selling the same amount of gas. But that’s another story, another story of Australia’s broken energy policy.

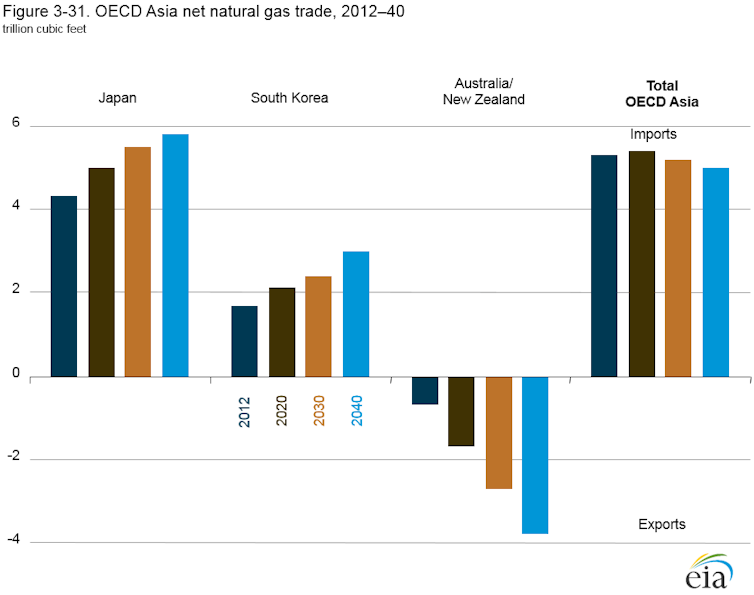

Japan, which is comfortably the world’s largest importer of gas at 34% of the global market, showed a 2% drop in imports last year just as the three LNG plants in Gladstone, Queensland, were ramping up production.

Japan has now begun re-exporting LNG, says Bruce Robertson. Its Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry estimates LNG demand will fall about 30% to 62 million tonnes by 2030.

The global gas industry closed out 2015 already in glut with total nameplate liquefaction capacity of 308 million tonnes (mt) surpassing demand for LNG imports of 245mt, by 26%.

While demand recedes across the world, the supply side looks ominous. By 2020, says Robertson, global LNG capacity is tipped to reach 400mt a year, up 30% on 2015. Some 92mtpa (million tonnes per annum) of new capacity will hit the global market between 2015 and 2020.

Meanwhile, Australia’s Office of the Chief Economist is predicting this:

Global LNG demand is expected to grow strongly to 2020 to approximately 457bcm (336 Mt), an annual increase of 5.9 per cent from 2014. … This growth is led by China, the rest of Asia and Europe, offset by falling demand in Japan. Demand growth has softened recently but the prospects remain positive overall.

The reality is that LNG trade grew by 2.5% in 2015, less than half the annual growth rate projected out to 2020 by the Office of the Chief Economist. Moreover, the key markets for Australian LNG producers are in North Asia. And in 2015, LNG demand in North Asia contracted by 1.7%.

It seems that, in gas as in electricity, over-cooked forecasts for demand have justified excessive spending and therefore ensured higher prices. This is precisely what the gas cartel wants: the spectre of shortages whipping up prices. They have been doing it for years.

While AGL was earnestly talking up gas shortages in 2014, BHP Petroleum chief Mike Yeager told journalists:

We want to make sure that the market knows that the Bass Strait field still has a large amount of gas that’s undeveloped … We have a lot of gas in eastern Australia that’s available. It’s more important to let the citizens of Victoria and New South Wales, and to some degree, you know, even Queensland … there’s plenty of gas to supply those provinces for – you know, indefinitely.

AGL later quietly issued a release to the ASX conceding it had plenty of gas supply.

Last September, Japan’s energy minister said imports of LNG would continue to fall. They fell by 4.7% in 2015 and another 2% in 2016 amid a rising commitment to renewables and the rebooting of nuclear reactors that were shut down after the Fukushima disaster.

They have also been falling in other parts of North Asia, down 9% year on year in the world’s second-largest import market, Korea.

Then there is China, which unlike Australia, is pursuing an aggressive transition to renewable energy while growing domestic gas capacity. The big swing factor here is the forecast 50mtpa of supply to come from Russia via two new Siberian pipelines.

Asian LNG imports peaked in 2014 and have been falling since, but what of emerging markets taking up the slack?

There is simply too much supply coming on line, says Bruce Robertson. While demand falls, global LNG capacity is tipped to rise by 30% between 2015 and 2020.

Contract defaults are already afoot. India’s Petronet has renegotiated its LNG contract with Qatar’s Rasgas, cutting the price in half over the 25-year term of the deal.

Meanwhile, the International Energy Agency (IEA), the energy adviser to the OECD, has pulled back its forecasts for gas demand for four years on the trot. IEA estimates growth in gas consumption will decelerate to 1.5% a year between 2015 and 2021.

Ironically, the very fact of a thermal coal market in structural decline and a global glut in gas conspire to push down fossil fuel prices and delay the transition to renewable energy. The gas cartel, though, by its actions in restricting domestic supply, is deliberately keeping prices high.

For its part, the government has been faithfully trotting out the cartel line that the states must bring new unconventional gas online, coal seam gas. This is not only expensive to produce but poses inestimable environmental risks to farmland thanks to the fracking process.

The cartel has manufactured a fake gas crisis. Australia is soaked in gas. The answer is a domestic reservation policy starting now.

This column, co-published by The Conversation with michaelwest.com.au, is part of the Democracy Futures series, a joint global initiative with the Sydney Democracy Network. The project aims to stimulate fresh thinking about the many challenges facing democracies in the 21st century.