Ask many Millennials – the generation currently in their late 20s to early 40s – about the possibility of home ownership and they will probably laugh in your face. The idea of getting a mortgage with just their own income is often unthinkable, and those who do own property often have an uncommonly early inheritance to thank.

While housing crises rage across Europe, many members of Generation Z – those born after the year 2000 – may soon find that the shoe is on the other foot. By analysing mortgage trends and other data, my research has predicted a gradual shift away from long term mortgage commitments among this generation.

Inheritances will play a key part in this change. Slowing population growth, smaller families, and a concentration of property ownership in the ageing Baby Boomer generation (born between 1946 and 1964) mean that inheritance rates have been climbing year on year.

Generation Z therefore stands to benefit from Europe’s declining birth rate, one of the lowest in the world at 1.53 children per woman. Put simply, there will be fewer young people to inherit houses, and more houses for them to inherit.

Mortgages: an increasingly unattractive prospect

Getting a mortgage is daunting at the best of times, as banks require savings, income, stable employment and a hefty deposit. If you meet these criteria, you are then locked into, on average, a 25-year commitment.

In a labour market characterised by temporary jobs and low, stagnating wages, many people will struggle to ever sign a mortgage, let alone pay one off. The prospect of getting one is especially unappealing at a time when rising mortgage rates are driving the cost of living up in Europe and beyond. This panorama is already affecting Generation Z’s attitude to long term milestones such as buying a home.

The fact that fewer mortgages are being signed across the continent is therefore unsurprising, especially given a steep rise in interest rates and soaring property prices. This decline seems set to continue into the long term, for a number of reasons.

Home ownership in Europe today

In the European Union, the average age at which people first acquire property is 34. The average mortgage duration is 25 years, meaning payments are typically completed by the age of 59, just before retirement age (65 in most EU member states).

As of 2022, 69.1% of Europeans owned their home, but only 24.7% had mortgages. This does vary widely across the continent, and there is little correlation between ownership rates and the number of active mortgages.

In some Northern European countries, the number of mortgages is actually rising. In the Netherlands, for example, 61% of homeowners currently have a mortgage.

In contrast, this percentage is far lower in countries like Italy, where only 14.6% of homeowners have a mortgage. This disparity may be due to the more common use of liquid funds, or stronger, more longstanding traditions of inheriting property in certain countries.

Spain: a case in point

We can take Spain as an example of the changes that are already underway. It is above average in life expectancy and rates of home ownership (especially among older generations): the average Spaniard first purchases property at age 41, and receives an inheritance at 51.

The number of inheritances, however, is reaching new highs year on year. From 2021 to 2022 the number of homes inherited in Spain rose by 3.7%, with over 17,800 homes inherited per month within its borders.

With only a 10-year gap, on average, between signing a mortgage and receiving an inheritance, the average Spanish person may see little benefit in tying themselves to a variable, potentially volatile 25-year loan.

Leaving the family home

The ongoing surge in property inheritance shows no signs of slowing, and is big enough to potentially decrease the long-term demand for mortgages. However, the value of inheritances varies widely across different countries and wealth distributions, and it is difficult to make predictions for all of Europe.

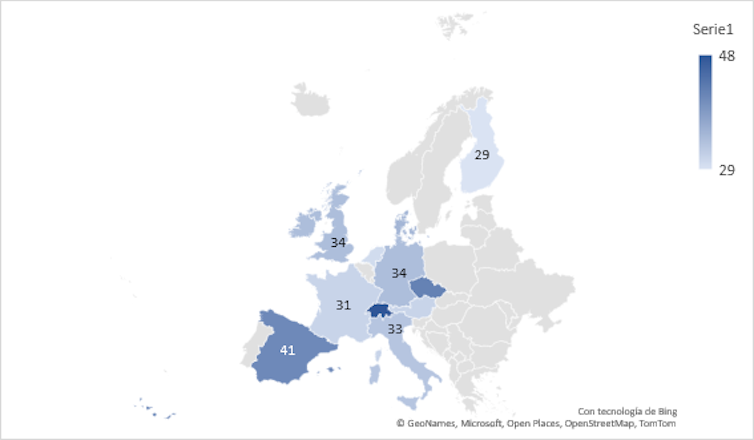

There is also huge variation in factors such as the age of leaving the family home. Southern Europe is generally higher in this regard, with adults typically staying with their parents until age 30.3 in Spain, 30.7 in Greece and 30 in Italy.

In Finland, on the other hand, people typically leave home at age 21.4, with similarly low figures across Scandinavia. France sees adults move out at 23.4, and Germany at 23.8. According to Eurostat data, many of these average ages showed long-term increases between 2012 and 2022.

However, higher youth independence does not directly correlate with more mortgage signings. Spain’s staggering drop of 62.54% in new mortgages from 2007 to 2023 is reflected in data from across Europe. From 2022 to 2023, Belgium recorded a 33.8% decrease, and between 2021 and 2022 France has witnessed an approximate decrease of 47.49%.

Annual data from the European Central Bank, released in November 2023, also shows annual decreases of 61% in Slovakia, 57% in Austria, 40% in Luxembourg, and 23% in Estonia. Across Europe as a whole, the number of new housing loans dropped by 32% last year.

Impacts on Generation Z

Though they will face plenty of other problems, such as securing stable employment contracts, housing might not be the primary concern for much of Generation Z in the future.

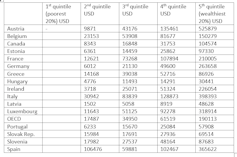

An ageing baby boomer population means that massive amounts of property are already being passed down among the wealthiest households: as far back as 2015, inheritances on average corresponded to $196,247 per person in the wealthiest 20% of OECD countries. This figure had already increased by 50% in less than a decade.

This will benefit Millennials to a certain extent, but with fewer siblings, many wealthier members of Generation Z might not need to divide inheritances from parents who often own multiple properties. This outlook, coupled with the conditions for accessing a mortgage in an inhospitable job market, will raise a simple question for much of Generation Z: Why take on the risk, long term commitment and extra cost of a mortgage if I don’t have to?