Presidential campaigns haven’t always looked the way they do in 2020 – or the way they did in 2016, before the coronavirus pandemic changed everything about conventions, political outreach and voting.

The requirements have stayed the same – just about any natural-born citizen over the age of 35 can run for president. But who decides who runs has changed substantially. So has campaigning.

Nowadays, people have to register as official candidates for president after they have raised US$5,000 toward the effort. At that point, the Federal Election Commission asks them to declare their political party affiliation, which they can choose even if the party leadership doesn’t want that person to run.

Party elites are still powerful, but in past eras, they were much more so.

The era of statesmen

When creating the presidency during the Constitutional Convention, many of the country’s founders saw George Washington as the ideal person to hold the office. Despite this consensus, they had a peculiar problem.

They thought anyone who sought the votes of the people wanted power for the wrong reasons and would use that power to undermine the government. For that reason, even Washington himself maintained a “guarded silence” on the topic to avoid appearing “vain-glorious,” admitting only privately that he would serve as the nation’s first president if he was called upon.

When combined with the very real fear that “those men who have overturned the liberties of republics” started “their career by paying an obsequious court to the people,” early candidates knew they had to avoid looking too eager for power.

Thomas Jefferson took this position to an extreme when he vowed never to serve in public office again after being the new nation’s first secretary of state. He discovered he would be on the ballot in 1796 only when his close friend James Madison wrote a letter claiming he “ought to be preparing” himself for the presidential nomination. Jefferson came in second that year, becoming the vice president; he won the top job in 1800.

Until 1824, candidates remained reserved about campaigning for themselves. That year, candidate Andrew Jackson stepped forward, promising to govern for the common man rather than the party elites who had controlled Washington for too long. The turbulence in the lead-up to, during and after the Civil War left elections more disorganized until the late 19th century, when the era of the machine began.

The rise of the political machine

After Reconstruction ended in 1877, American politics was a dirty business. Party elites sat in smoke-filled rooms deciding whom they would support as a candidate and how they would stop others from winning the election.

Once in office, members of both parties used their position to provide others with patronage jobs and expected kickbacks as thanks. Party bosses usually maintained control over those in power, even demanding a say in who served in the positions that were appointed by elected officials.

As New York City’s police commissioner and later governor of New York state, Theodore Roosevelt resisted the system so much that an aggravated party boss strong-armed members of the Republican Party into offering the ambitious politician the notoriously powerless post of vice president. The scheming backfired, however, when President William McKinley was assassinated in 1901. Roosevelt became president and instituted a variety of progressive reforms, like hiring for merit rather than favoritism, some of which helped diminish the power of party bosses.

By the 1920s, candidates had an even easier way to sidestep the party elites: the invention of the radio.

The first communication revolution

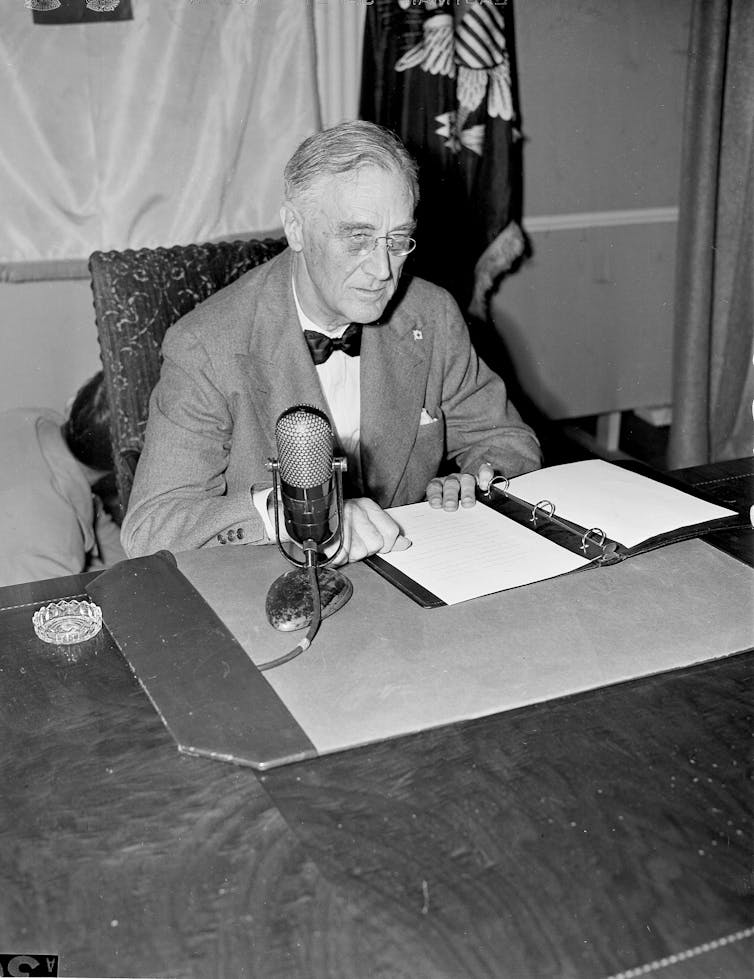

The invention of the radio soon led to a watershed moment for democratization. Through this medium, presidents could speak directly to the citizens, creating a more visceral connection between the country’s leader and its people.

Eager for popular content, broadcasters gained access to nominating conventions and sold radios by claiming the people could get an inside look at the process. With the addition of television in the early 1950s, candidates started hiring advertisers to determine how to “sell” themselves directly to the people, rather than going through the party.

By 1968, when the Democratic Party ignored the results of the primaries and nominated Hubert Humphrey for president, the rioting in Chicago reached a boiling point, leading to reforms. The primary elections became more influential, and the elites lost more of their power. In 1976, however, Jimmy Carter’s surprising win in Iowa caused Democrats to claw back some control by creating superdelegates, individuals selected by the party who could give their vote to a candidate and potentially overcome the results of the primaries. These efforts worked relatively well – until the creation of social media.

The second communication revolution

During the 2008 Democratic primary, almost everyone assumed Hillary Clinton’s time had come. Political players and pundits alike expected people would vote accordingly; very few took Barack Obama’s candidacy seriously. They thought the self-proclaimed “skinny kid with a funny name” would learn the ropes and maybe get a Cabinet post.

Instead, Obama revolutionized campaigning by using the “tremendous communication capacity” of social media to spread his message and recruit volunteers. Obama harnessed the energy created by platforms designed to bring “friends” together and allow them to share their interests among anyone in their network. When coupled with his ability to bring a crowd to its feet – and a very friendly media – Clinton and the party backing her did not stand a chance: The people wanted hope and change.

The people surprised the elites once again in 2016. Donald Trump offered a unique vision of a country in disrepair that needed an outsider to come in and make America great again.

Republican operators like Reince Priebus and Paul Ryan did not take him seriously, nor did the media. Many believed Clinton would beat him handily.

Once again, elites did not realize the power of social media – this time to divide the country. The powerful algorithms used by various media platforms dramatically increased the amount of radical content people saw.

Simultaneously, Donald Trump fed the feeling of injustice among some in the country, claiming he would work for the “forgotten men and women.” The sustained feeling of injustice among many groups and the violent actions deployed to address them remains an element of the current election, where once again a brash outsider (who is also the incumbent) battles a respected party elder in good standing.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Each president leaves a permanent mark on the office. The last two presidents have fully capitalized on the power of the internet to connect them to the people. How future presidents will use these tools, and whatever new tools are yet to come, is difficult to predict. It is easy to see how mediums like Twitter and YouTube can maintain a connection and can convey small pieces of information.

It is also possible to see the value in creating a community through social media to help broadcast a political message through networks of supporters and their friends. It is difficult, however, to think back upon the great speeches of America’s past presidents and see how they could repackage those stirring moments into 280 characters.