Fears for the so-called lost generation look more valid by the day. Britain’s chancellor might have the confidence to target full employment, but the problem of getting young people into work is a genuine challenge and one which we cannot afford to leave to market forces alone.

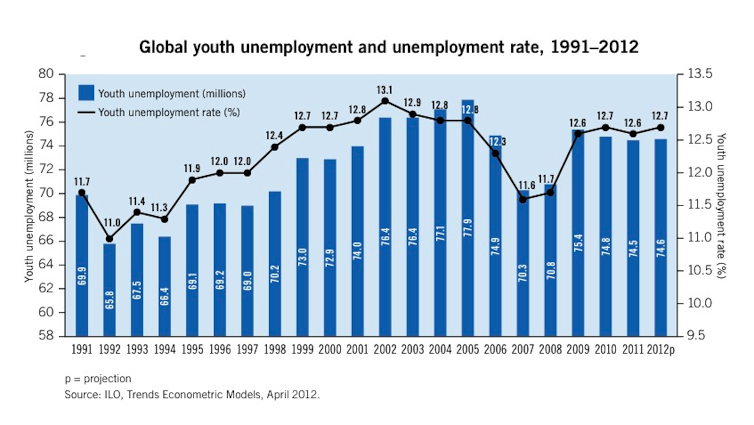

The latest numbers out of the eurozone bear this out. The youth unemployment rate may have dipped a little but we are still close to record highs. The pattern is repeated worldwide. Our pursuit of a recovery has given us a form of growth, if not the illusion of it, which sidelines the people we need to build a post-crisis economic model that works for everyone.

So why is our timidly recovering economy failing to drag youth employment along with it?

Looking at global trends between 2008 and 2013, it’s easy to see the world is once again becoming a busy producer of goods and services and maybe we are tempted to believe that some kind of “second chance” is also being produced. Exports are on the rise, and with them global GDP indicators, so if the world was one system (it is but we decide not to acknowledge it), the overall trend would be slightly positive.

But productivity-driven growth is coming at the expense of direct investment across national borders, which is shrinking. Foreign investment may still be playing an important role in contributing to national GDPs, but the actual inflow of capital has been negative. Countries around the world are experiencing declines – with the exception of Africa and some economies in Latin America which are gearing up for significant economic growth in the years to come.

Chasing growth

The lack of incoming capital reveals a gap between investments and the real economy. It means, in other words, that the growth of capital is faster than the growth of the economy, and this is usually demonstrated in wealth accumulation towards the upper 25% of the wealth distribution chain. The consequence is fewer high-end job opportunities and more labour-intensive jobs aimed at a less skilled workforce, which is what produces visible incidences on national GDPs.

Governments are subsidising low-end jobs at the expense of genuinely value-creating businesses. Skilled workers are becoming unemployed as the economy fails to provide them with suitable jobs because we are simplifying our value chains. It means we structurally reduce high-end, well-paid jobs in exchange for fast-moving, low-end, consumer-linked roles. This is a recipe for disaster, given that the only way we can achieve real social and economic progress is by raising our productivity standards, not our speed.

If the above graph presents a picture of private-sector growth, what about the governments? How are they coping with the challenges of the 21st century? So far, they have reacted to increased socio-economic pressure by lowering interest rates and implementing austerity measures.

Worse yet, the unemployment crisis, especially among the young, is just the tip of an immeasurably large iceberg. It indicates an underlying problem in the way our economies function: growth. As we continue to expand, unemployment will only get worse. It’s a problem that spans all countries, regions, markets and democracies, whether old or new. Yet, at the same time, we do not have a solution – certainly not a universal one – to tackle this problem.

Beyond GDP

All of this comes at a cost – one that has been building over the past 50 years but is only now becoming apparent: more pressure on the middle classes, which form the majority of most advanced economies. The world’s middle class is being squeezed by a lack of innovation, investment and skilled jobs on one side, and harsher cuts to public spending and the prospect of higher borrowing costs on the other. Inefficiency has crept into the economy and with it the threat of social instability.

Not all is lost, however. The world economy may still find a way to adapt to its new circumstances. From a fragmented and unequal world, we have become a hyper-connected collection of economies – albeit thwarted ones – united in our search for a new business model.

This new model is right in front of our eyes. The world’s millions of young people, with their talent for innovation and ease with radical disruption, find themselves excluded from the workforce. They are naturally versatile and restless; young people could be the antidote to our poisoned economic systems.

If governments and the private sector could co-ordinate their efforts to capitalise on this overlooked generation, everyone would benefit. It’s not simply about boosting entrepreneurship or even innovation-driven start-ups; it is more fundamental than that. We need to allow young people a stake in our collective future by respecting their abilities, giving them a say, encouraging them to vote and providing them with quality education and the right training. Only this can make them feel less disowned.

It will take a change of culture; a little imagination, a tiny bit of decency and a softening of the dogmatic assertion that quantifiable growth is the only worthwhile measure. Quite simply, we need governments, companies – and people – to upgrade their mental model to one of inclusiveness, beyond GDP.