François Hollande joins a long tradition of French Fifth republic Presidents who have had affairs. Widespread attachment to France’s privacy laws, and a press corps that generally agrees with them, combined with a generalised reverence for the office of the presidency have meant that rumours always remained largely rumours – until now.

In the past, gossip did no harm because there was always and still is a generally more indulgent attitude to affairs of the heart and tolerance of “liaisons” by both men and women (especially men). There has also been the conviction throughout French history that power is the strongest aphrodisiac both for those who exercise it and those fascinated by it.

The nearest Charles de Gaulle got to sexual scandal was his wife Yvonne being asked by an English reporter what was the most important thing in her life, to which she replied “A penis” (say “happiness” slowly with a French accent). But stories of sexual intrigue – probably secret service smears – surrounded the Pompidous.

But Valery Giscard d’Estaing set the tone, and he encouraged it, seeing himself as a true Don Juan. Rumours still abound of many liaisons – did he and the softcore star Sylvia Kristel have an affair in the Elysée? Who was the woman in the Ferrari he was with when, driving though Paris in the early hours, he hit a milk van? He even happily encouraged rumours about himself, for example, that a president just like him had an affair with a princess just like Diana.

Mitterrand was also linked to many women, including the editor of Elle, Françoise Giroud, the singer Dalida, and many more. Rumour became fact when he revealed he had raised a second secret family, and a secret daughter Mazarine, at the state’s expense. Ah les beaux jours!

The tone changed from the stylish and Romanesque to testosterone-fuelled vulgarity with Jacques Chirac, known by his chauffeur (and then the world) as “Mr 15 minutes, shower included”. His highly popular and respected wife, Bernadette Chirac, started a sea-change in attitudes when, in her best-selling autobiography, she wrote touchingly and honestly about how painful that aspect of her marriage had been.

Hollande’s predecessor Nicolas Sarkozy reportedly had affairs with journalists, including, allegedly Chirac’s daughter Claude, but his dalliances and his very public life with second wife Cécilia Sarkozy and later Carla Bruni were seen more as the uncontrollable passions of a (short) man with uncontrollable ambition, an uncontrollable temper, and an uncontrollable desire for attention and affection.

Sadly comical

Even with that history behind thim there are five things which make Hollande’s alleged affair with the actress, Julie Gayet, sadly comical and politically dangerous. First is the sea-change mentioned earlier. Attitudes have shifted, not so much about sexual mores and the weaknesses of the flesh – in fact, with the decline in religious observance, things are even more liberal. But cheating on your wife or partner, with such intensity and frequency is seen – even in France – as sexist and the sign of a patriarchal society of inequality and disrespect. And sending your partner, Valérie Trierweiler, into hospital in a state of nervous collapse is not seen as the act of a man of integrity.

Second, Hollande came in to stop all this stuff. He was “Mr Normal” who was going to bring exemplary conduct to political life, and stop all the tabloid press gossip lowering the status of the presidency. He said so himself. In fact, his somewhat tortured relationships with former presidential candidate Ségolène Royal, Trierweiler, and now Gayet have never been out of the headlines.

Third, there is something comical and diminishing of the presidency in his slipping out not in a Ferrari but on the back of a scooter (driven by his chauffeur who also buys the croissants – you could not make this up), the easy victim of Closer paparazzi, Sébastien Valiela, waiting, camera at the ready, across the street.

Fourth, there is the question of security. Why does he need bodyguards all around him in public when he takes such risks in private? It was fortunate it was not an al-Qaeda hit squad on the other side of the street.

Finally, even before this incident, he was the most unpopular president of the Fifth Republic to date. If he had had any success with the unemployment figures or the stagnating economy since he had been elected, perhaps the French might think he deserved a night off; the French presidency is now like the post of a CEO whose full-time job it is to sort out France Inc, and the efficiency and health of its political and social institutions. Affairs at the office are no longer part of the job description.

Slow to catch up

French commentators in the political class and the media seem to be catching up with the significance of all these things very slowly. There seems to be a severe case of cognitive dissonance on their part regarding what is at stake here because, of course, the president does not have a private life like everyone else. He’s the president.

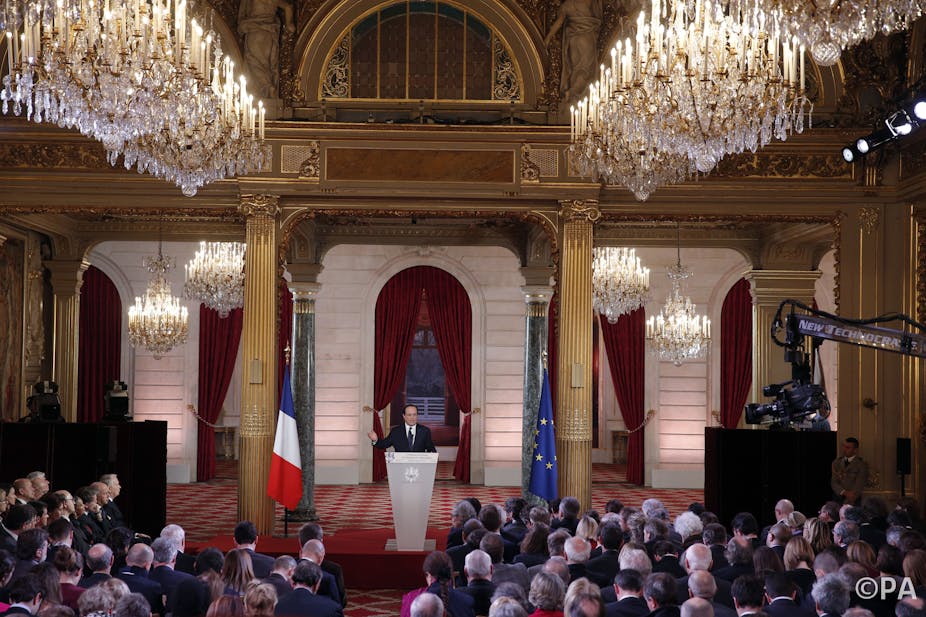

Besides, when things are going well, the “private life” is deliberately on display for all to see. That is how the French presidency thrives. Before his first press conference after the scandal broke which, for once, everybody watched, he had three choices regarding his very public affair: say something before, say something during, or say nothing. Each would be consequential in its effects.

He chose the last, almost, saying he would not answer questions on issues of his private life, but would respond in the coming days (before he – and Valérie – are scheduled to visit the Obamas in mid-February).

It is clear that he, and all the commentators, and the political class are now thinking about redefining the status of the French first lady. It is as if virtually the whole country is in in denial. Politics would be far better served if, rather than redefine the role and status of the first lady, France were to redefine the role and status of the presidency itself.