Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stated that “housing isn’t a primary federal responsibility” at a funding announcement in Hamilton, Ont. on July 31.

This statement is neither accurate nor politically smart, with recent polls suggesting that 70 per cent of Canadians think the Liberal government isn’t adequately addressing the high and growing cost of housing.

While the word “housing” isn’t mentioned in the 1867 Constitution Act or 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms as a federal, provincial or municipal responsibility, the rights to “life, liberty and security of the person” as well as “equal protection” in the Charter can’t be achieved without adequate housing.

The right to housing — which Canada has promised to enforce in numerous international covenants — was enshrined in Canadian law by the current government in 2019.

Instead of taking responsibility for the housing needs of Canadians, the federal government has been participating in the same “ambiguity, turf guarding, buck passing and finger pointing” they accuse other governments of doing, as was recently seen in the treatment of refugee claimants in Toronto.

History of federal housing engagement

Trudeau seems to have forgotten about the federal government’s previous involvement in housing. After the Second World War, the Canadian government helped create a million low-cost Victory Houses using government land, direct grants and industrialized production processes that allowed new homes to be assembled in as little as 36 hours.

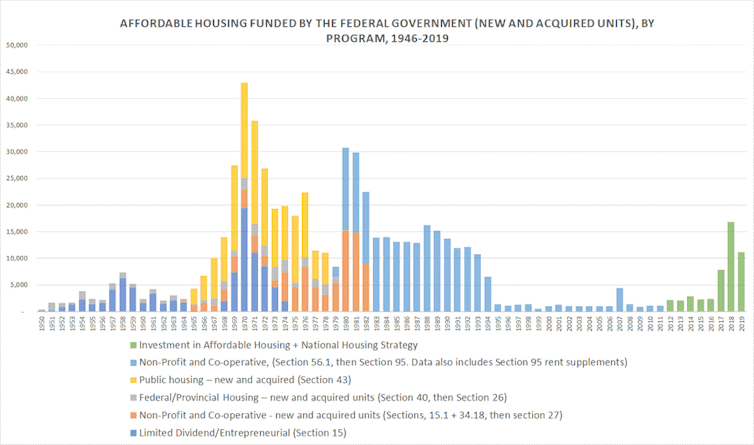

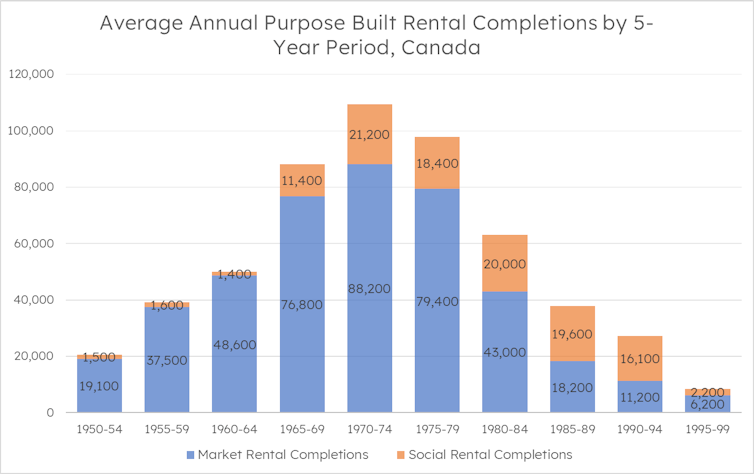

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s, between 10 and 20 per cent of new construction was non-market housing — public, community and co-op — supported through federal land, grants and financing partnerships with provincial and municipal governments.

Read more: New study reveals intensified housing inequality in Canada from 1981 to 2016

As a result of federal government actions, the average home cost 2.5 times the average household income in 1980. Today, the average home in Canada costs 8.8 times the average income, with homes in Toronto and Vancouver costing 13.2 and 14.4 times respectively.

The production of non-market housing fell off a cliff in 1992 when the federal government downloaded responsibility for affordable housing to provinces.

Private rental construction dropped precipitously after 1972 when the federal government cut back on taxation incentives. The housing crisis has its roots in the federal government’s neglect of affordable housing over decades.

Five priorities for the federal government

There is an opportunity for real federal leadership with the recent announcement that Sean Fraser will take on a combined Ministry of Housing, Infrastructure and Communities. Rather than dodging responsibility, the federal government should pursue five priorities.

First, the federal government must return to using a single income-based definition of affordable housing in its programs, as it did from the 1940s to the 1990s.

Evidence-based supply targets for provinces and municipalities would reflect the fact that 78 per cent of households in need of housing can afford no more than $1,050 a month for rent and homeless people no more than $420 a month.

Second, delivery of genuinely affordable housing — including a fair share of Indigenous housing built by and for Indigenous people — will require land from all three levels of government, grants to non-market housing providers and low-cost financing.

Scotiabank’s recommendation to double non-market stock with 655,000 new or acquired homes over the next decade is a starting point to eradicating homelessness by 2030 and reducing the core housing needs of 530,000 families by 2028.

Third, a progressive surtax placed on the most expensive homes in Canada, or redressing the $3.2 trillion capital gains tax shelter for principal residences, could fund an improved National Housing Strategy with a stronger focus on those who need housing the most.

Fourth, the government must meet the needs of its rapidly growing population and ensure middle-income families can afford to raise their children in urban areas.

Taxation reform and offering long-term, low-cost financing for purpose-built rental homes are both federal government responsibilities. So is supporting Canadian firms to become world leaders in prefabricated modular housing.

Provinces and municipalities must step up

The final priority the federal government should consider is using conditional agreements for infrastructure funding to encourage other levels of government to do more.

Provincial and territorial welfare rates and minimum wages don’t match housing costs. Insufficient provincial funding for health and social supports has put federal rapid housing initiatives at risk.

Provinces must improve residential tenancy protections to stop the rising tide of evictions and double-digit rent increases. Municipalities need to revise zoning codes to allow four- to six-storey buildings in all residential areas and 10- to 30-storey buildings close to rapid transit stations.

Municipalities must stop making it harder for multi-unit housing to be built. Barriers, including placing restrictions on how many units can be built, setting parking requirements, imposing onerous development charges and elaborate design requirements, must be eliminated.

By amending the federal building code, municipalities could scale up smaller, affordable, accessible and energy-efficient apartment buildings with family-sized units.

Rather than passing the buck for housing, the federal government must take the lead on affordable housing supply, the most pressing issue Canadians are facing today.