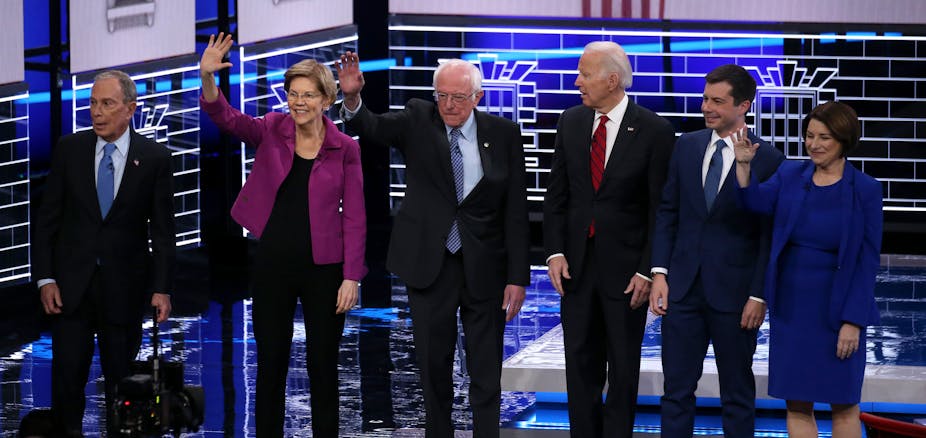

Editor’s note: Six Democratic candidates met on the debate stage in Las Vegas on Feb. 19, discussing health care, immigration, billionaires and economic equality – as well as the name of the president of Mexico. We asked two scholars to pick out what they viewed as the night’s biggest moments as Nevada Democrats get ready for their caucuses on Feb. 22.

Both Lisa DeFrank-Cole, a professor of leadership studies at West Virginia University, and Jeffrey Waddoups, a professor of economics at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, highlighted moments when Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren engaged in a fierce back-and-forth across the stage.

Lisa DeFrank-Cole, West Virginia University

Elizabeth Warren: “Can I defend Senator Klobuchar for a minute? Look, you want to ask about whether or not you understand trade policy with Mexico? Have at it. If you get it wrong, you ought to be held accountable. … Let’s be clear: Missing a name all by itself does not indicate that you do not understand what is going on.”

In an era of political leaders bullying those they disagree with, it is refreshing to see one stand up for a competitor.

Even though Warren attacked Amy Klobuchar’s health care policy by saying it could fit on a “Post-it note,” she stood up for her colleague during another exchange, when Klobuchar was weathering criticism that she hadn’t remembered the name of Mexico’s president. Warren’s dual role of critic and defender in the debate reflects a challenge every woman leader faces.

Though a recent Gallup Poll found most Americans say they would vote for a woman for president, it is still not a sure thing. Society still expects women to be nurturing and helpful, not argumentative or decisive. Men, on the other hand, can be tough and strong with little or no regard for kindness.

It is hard for a woman leader to be seen as both likable and competent at the same time. This double bind makes it a challenge for women on the campaign trail like Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar. They need to project warmth and compassion while also demonstrating the ability to get the job done. Their task is difficult: Be smart, but not arrogant. Be kind, but not weak. Be feminine, but not emotional.

In addition, it’s dangerous to focus on being a woman and to seek sympathy for having a harder time than your male competitors.

By attacking one of Klobuchar’s policies, and then within the same debate coming back to defend her fellow senator, Warren is projecting warmth and compassion. This is the dance that women leaders do every day: Take two steps toward strength and one step back to show kindness. It’s a dizzying maneuver to master.

Jeffrey Waddoups, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Elizabeth Warren: “This country has worked for the rich for a long time and left everyone else in the dirt.”

There was a time in U.S. history when prosperity was more or less equitably shared across all economic classes. During the period that started just after World War II until 1978, increases in the minimum wage and the income of the median household reliably matched up with rising productivity of the overall economy.

During those years, increasing prosperity in the overall economy generally translated into proportionate increases in the prosperity of workers and middle-income households. In a real sense, the economy was working not only for the wealthy, but for middle-income and lower-income workers as well.

Then things shifted: Starting in the late 1970s, productivity as measured by output per worker continued its upward march. But the economic well-being of middle- and lower-income employees stagnated. Most workers were no longer sharing proportionately in the economy’s prosperity.

That disconnection was accompanied by the weakening of two important forces for better wages: a minimum wage that tracked with inflation, and widespread collective bargaining. Both of those elements give workers power – which Nevada’s Culinary Workers Union wants to protect.

The current federal minimum wage is US$7.25 per hour, a number that has not risen since 2009. That amount has roughly 30% less buying power than the $1.60 hourly minimum wage in 1968, an amount worth $10.15 in today’s dollars, when adjusted for inflation. Many state and local governments have set higher minimum wages, but hundreds of thousands of workers across the country are earning the federal minimum.

Similarly, union representation has dropped since the 1970s. In 1979, 27% of American workers were represented by unions. In 2019, that number was just 11.6% – meaning millions of workers today don’t have the bargaining power to get wages and working conditions that similarly situated workers in the past enjoyed.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]