The Parliamentary Budget Officer recently released an updated analysis of the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on the Canadian economy that forecasts the federal budget deficit will be $252 billion in 2020-21, compared to $25 billion in 2019‑20.

Such a massive deficit would represent 12.7 per cent of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product. In comparison, the deficit for 2019-20 is expected to be be only 1.1 per cent of GDP, according to the PBO’s analysis.

The increase in the deficit is mainly caused by the fall in tax revenues resulting from the lockdown-induced recession and the extraordinary spending measures adopted by the government to support the economy and manage the pandemic. The PBO says these measures totalled $146 billion as of April 24.

So, where is the money for all this extra spending coming from?

With tax revenues down, the only option right now is borrowing. But who can lend the government such large sums? At what cost? And how are Canadians going to pay it all back? Is the federal government going to have to raise taxes and cut regular spending once the COVID-19 crisis is over?

Cost to taxpayers should be minimal

The good news is that the cost to Canadian taxpayers and beneficiaries of government services should be minimal. Canadians do not have to fear years of austerity from their federal government once the pandemic has passed.

Domestic and foreign financial institutions (banks, insurance companies, pensions funds and other investment funds) and large corporations are the federal government’s main lenders. They do so by buying bonds (essentially contracts where the borrower pays lenders or investors a fixed rate of return over a certain period of time) from the federal government.

Demand and supply determine the interest rates the government pays to the investors on these bonds. If there is a lot of demand for the government’s bonds relative to their supply, then interest rates will be low. If demand is low, then interest rates will be high.

In the current context, we would expect the demand for Canadian government bonds to be low and their supply to be high. With the economy in recession because of the pandemic, financial institutions and most large companies are struggling. It’s likely they don’t have much spare cash to invest in the vast amounts of bonds offered by the federal government. As a result, the government would be expected to pay high interest rates on its extra COVID-19 borrowing to attract investors.

Interest rates have dropped

The reality is, however, the opposite. According to the Bank of Canada, interest rates on government bonds have dropped significantly in the past two months. Canadians can thank the Bank of Canada for this fortunate turn of events. The bank’s unprecedented actions to support the economy and financial markets during the COVID-19 crisis have brought down the cost of borrowing.

One such action is the Government of Canada Bond Purchase Program, whereby the Bank of Canada purchases a minimum of $5 billion worth of federal government bonds per week in the so-called secondary market (from financial institutions and corporations), as opposed to directly from the government itself (the primary market).

In doing so, Canada’s central bank has indirectly pushed up the demand for federal government bonds. In fact, it is as if the Bank of Canada was lending directly to the government at very low interest rates.

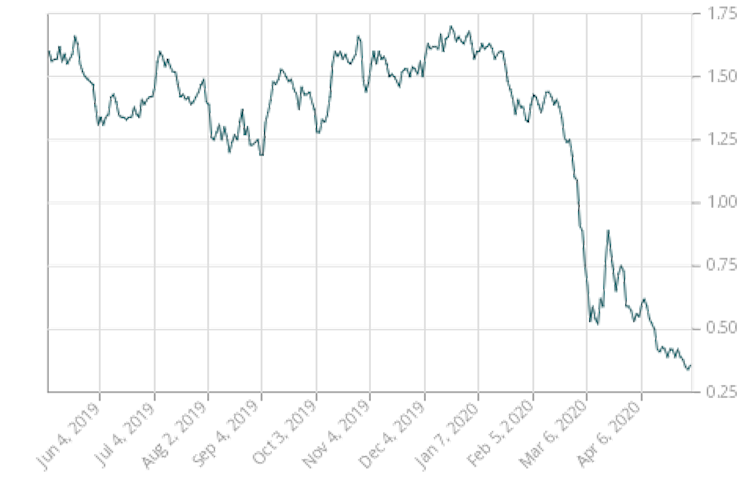

As a result, the federal government’s cost of borrowing is now lower than it was a couple months ago. For instance, it currently costs the government 0.35 cents for every dollar that it borrows for three to five years. Back in February, it was paying between 1.25 and 1.75 cents per dollar borrowed for the same period of time.

This means the annual cost of borrowing $252 billion for three to five years would be only $882 million, compared to the $3.8 billion it would have cost without the Bank of Canada’s actions. Such a sum would add only 0.04 per cent of GDP to the federal government’s future yearly deficits. It can, therefore, be easily absorbed without raising taxes or cutting regular program spending in the future.

But what about paying back all the extra debt? Won’t that require raising taxes and cutting spending for the foreseeable future? Not necessarily.

Debt will be rolled over

Assuming federal government spending and the Canadian economy go back to some kind of normal when the pandemic is over, then the government will simply be able to roll over its debt into the future and, therefore, not have to pay back any of it — possibly forever.

In other words, as long as investors are willing to buy the government’s bonds, then it can issue new bonds to pay back old bonds that are coming due. And if the economy grows faster than the deficit, then the debt-to-GDP ratio decreases, as it has in the last decade.

So Canadians will not have to suffer twice for the coronavirus pandemic: first by being locked down and then by paying higher taxes and/or experiencing cuts to regular federal government programs.

Instead, they should thank the government for doing the right thing by reducing the economic and social harm caused by the pandemic lockdown at little cost to future public finances. They should also thank the Bank of Canada and its outgoing governor, Stephen Poloz, for making it all possible.