MEDIA & DEMOCRACY: In the latest instalment of The Conversation’s week-long series on how the media influences the way our representatives develop policy, Andrew Norton says there’s no need to regulate third party spending. Marian Sawer disagrees. Read her take here.

For a non-election year, we’ve seen a lot of political advertising — and little of it has been from the political parties.

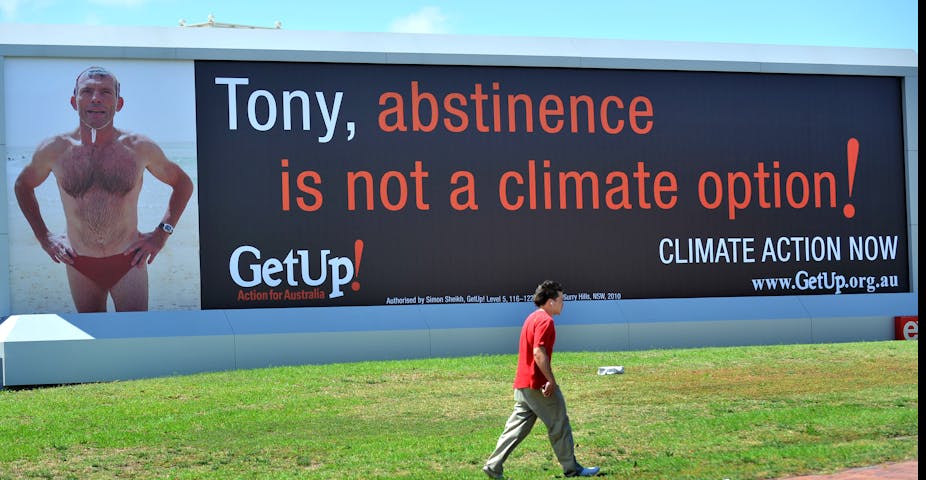

We’ve seen Cate Blanchett and the coal industry present opposing sides of the carbon tax debate. The pokies lobby and GetUp! have jousted over plans to limit betting on poker machines. And the tobacco industry is fighting a noisy media campaign against plain packaging laws for cigarettes.

For some people, these campaigns are signs of a robust democracy. But for others, they are a problem to be fixed, or at least alleviated, by campaign finance law.

The power of third parties

Writing in Inside Story earlier this year, campaign finance law expert Graeme Orr warned of the “risk unrestrained advertising poses to political equality”. After all, few of us can afford the $15.8 million the ACTU spent in 2007 opposing WorkChoices, or the $22 million the mining industry spent in 2010 opposing the resources rent tax.

Senior journalists have objected to third party campaigns on public interest grounds. Katharine Murphy in The Age worries about a political system in which nothing can be done because vested interests set the agenda. Peter Hartcher expressed similar views in the Sydney Morning Herald.

The party line

Unsurprisingly, many people in the political parties agree that third parties are too powerful. Several Australian jurisdictions have for years had third party expenditure and donations disclosure systems. Since late last year NSW and Queensland have both moved to severely restrict third party campaigns.

During state election campaigns, third parties in NSW and Queensland are now limited in how much they can spend. In NSW, third parties can spend the equivalent of 23 cents a voter, compared to $2 a voter for political parties.

In Queensland, the disparity is even wider, with third parties allowed to spend the equivalent of 18 cents a voter, while political parties can spend $2.60 a voter. With multiple media markets in each state, third parties won’t be able to reach all voters with electronic advertising.

Expenditure limits apply only during campaign periods — starting in October, the year before the fixed March election date in NSW, and generally two years after the last state election in Queensland. But limits on donations now apply at all times. In both states, the donations cap favours political parties over third parties. Donors can give $5,000 to a political party, but only $2,000 to a third party.

And of course, the political parties also have generous public campaign funding, as well as new “administration” funding in NSW and Queensland. Third parties have no public funding entitlements.

Governing political parties can dip further into taxpayer funds to finance advertising their policies. These advertisements cannot be directly partisan, but they can present just one side of an issue — often contrary to the views or interests of a third party.

Too much influence?

Underlying the argument for more regulation of third parties is the view that at least some of them have too much influence.

But no third party can match the resources or legislative power of the state, as used by the governing party or parties.

Most third party campaigns arise because the interests or views of the third party are threatened by some actual or proposed government policy. If there wasn’t a power imbalance against third parties, most third party campaigns would not exist. A public third party campaign is a direct appeal to the voters, the final judges in a democratic system.

Essential to democracy

The practical effect of third party campaign finance laws is that the state can do what it likes to third parties, but they have only a limited licence to protest.

If third parties or their supporters breach the terms of their licence to protest they face fines and, in some cases, jail. It is an extremely concerning criminalisation of ordinary political activity.

While it is true that some third parties have much greater resources than others, wealthy third parties or coalitions of third parties are an important part of a well-functioning democratic system.

For democratic systems to work effectively, governments must fear the loss of office. And that means that opposition political groups must be able to put together a political force larger than the political force behind the government. Third party campaigns, along with their donations direct to opposition political parties, are part of putting together that political force.

Votes are not for sale

It is also important to keep third party campaigns in perspective. The idea that opinion or votes can simply be bought by big-spending campaigns is not supported by the evidence.

Pre-existing public opinion on a subject often resists change. Third party campaigns are frequently met with strong counter-campaigns, from other third parties, political parties, and the government.

But unless third parties can directly communicate with the public, without their views being mediated by media news judgments, or the biases of journalists and newspaper proprietors, often their views will not be heard by voters.

The system should not judge

Most of us have personal views about which third party campaigns are good and which are bad, but it is important that the political system itself not prejudge the matter.

Inevitably, that will mean that governing political parties set the rules to suit themselves, as has happened in NSW and Queensland.

The same rules — and preferably very few rules — should apply to everyone in democratic politics.

This is the eleventh part of our Media and Democracy series. To read the other instalments, follow the links here:.

Part One: Selling climate uncertainty: misinformation in the media

Part Two: Forget the fantasy politics - advertising is no substitute for debate

Part Three: Democracy is dead, long live political marketing

Part Four: Selling the political message: what makes a good advert?

Part Five: Drowning out the truth about the Great Barrier Reef

Part Six: Event Horizon: the black hole in The Australian’s climate change coverage

Part Seven: Spinning it: the power and influence of the government advisor

Part Eight: Cops, robbers and shock jocks: the media and criminal justice policy

Part Nine: Bad tidings: reporting on sea level rise in Australia is all washed up

Part Ten: Big money politics: why we need third party regulation

Part Eleven: Power imbalance: why we don’t need more third party regulation

Part Twelve: Scientists vs farmers? How the media threw the climate ‘debate’ off balance

Part Thirteen: Warning: Your journalism may contain deception, inaccuracies and a hidden agenda

Part Fourteen: The hidden media powers that undermine democracy