The federal government has tabled the long-awaited Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) report into children held in immigration detention. The report, which recommends a royal commission be held into the issue, has been subject to intense politicisation. This has included the AHRC and its president, Gillian Triggs, coming in for criticism from government MPs and media commentators.

The report found that children in immigration detention had been involved in nearly 300 instances of actual or threatened self-harm between January 2013 and March 2014. It also revealed that more than one-third of children detained have developed a mental illness requiring psychiatric care.

The Conversation’s experts assessed the report’s implications for asylum seeker law, policy and health. Their responses follow.

Malcolm Fraser, Professorial Fellow at University of Melbourne

Enough is enough. The government had the report on November 11 last year. It has tabled it on the last possible day. It is now clear that the attacks made on the AHRC, especially by senior ministers, has been designed to make it easier for the government to ignore the AHRC’s report.

The government’s response is a disgrace. It is based on a lie. It claims to have saved lives by stopping the boats and that the trauma inflicted on children by detaining them, is a small price to pay. It deliberately chose an inhumane way of stopping the boats.

If the Australian government worked with our regional neighbours and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to process people humanely in offshore detention centres in Malaysia or Indonesia, then there would be no market for people smugglers. Refugees would be flown to their final destination. This is not supposition or hearsay. This was the policy model adopted during the exodus of refugees fleeing Indochina following the Vietnam War. It would work again.

The real question for the government is why did it choose to do this, despite the trauma and harm done to hundreds of children, when there was a decent and proven way of achieving a much better result.

The attack on the integrity of the AHRC and its president, Gillian Triggs, is only to be expected of this government, who uses bullying as their default tactic. The attack is consistent with the way the government has approached legal decisions that have gone against it. This government has also refused to listen to our highest court, undermining the rule of law and ignoring international law.

The only conclusion we can really draw is that the inhumanity inflicted on these children is part of a policy of deterrence, which the government has pursued relentlessly. Australians needs to understand that this government has chosen an inhumane path when a compassionate path was available to it.

David Isaacs, Professor of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at University of Sydney and Hasantha Gunasekera, Senior Lecturer, Paediatrics & Child Health at University of Sydney

When faced with the meticulously compiled report on children in detention, the government had two choices – respond to the substance or discredit the messenger with personal attacks. Unfortunately, it chose the latter – a sad indictment of current political debate.

For two decades, each government contributed to the current state of affairs. Keating introduced mandatory detention; Howard offshore processing; Gillard Malaysian rendition; Rudd barred visas; and Abbott turned back boats. This is beyond partisan politics. Asylum seekers have committed no crime, whether they arrive by plane or by boat, yet both sides of politics demonise them and treat them worse than criminals.

The current government boasts that the number of children in detention has fallen from nearly 2000 to 211. However, 119 children remain on Nauru, detained in inhumane conditions for an average 18 months. Their families are in limbo not knowing when, if ever, their refugee applications will be processed.

Prime Minister Tony Abbott used drownings at sea to justify the harsh policies. However, every parent has to decide which danger is greater: staying in their war-torn country; remaining in dangerous refugee camps in Indonesia; or the risk of drowning. Do any of us know better than them which is the greatest risk?

Offshore detention patently failed to stop the boats. Prime Minister Julia Gillard re-introduced offshore detention in 2012, and the boats continued to arrive regardless.

In addition to being immoral and ineffective, mandatory detention of children is also extraordinarily expensive. According to the government’s own response to questions on notice, last financial year the government spent A$1.2 billion operating the detention centres on Christmas Island, Manus Island and Nauru. On average, it cost taxpayers $422,800 in one year for each person held on Manus Island and $529,000 for each person detained on Nauru.

Catherine Smith, PhD Candidate in the Sociology of Education at Deakin University

The press and politicians are finger-pointing and shifting blame in response to the report’s release. It is likely that Australia has broken the international Convention on the Rights of the Child. This disregard for international conventions is not unprecedented within the immigration practices of the last 12 months, and the ramifications of this are still to unfold.

At the meta-level, these debates are global ones. There are more displaced people in the world today than there were after the Second World War. Around half of them are under 18. This means that there is a crises or global proportions involving millions of children who have had disrupted, traumatic childhoods where they have often been deprived of the essential elements of care which allow a child to flourish.

These are trapped children. Their parents have arrived somewhere, asked for protection, and been caught within the bureaucratic machine which encases their childhood in detention facilities, while the finger-pointing and blame shifting rages overhead.

Detention centres are highly securitised settings. Researchers have described the:

… negative nature of the detention environment as ‘corrosive places’, ascribing it explicit culpability in the frequency of self-harming behaviour and growing rates of mental illnesses.

Additionally, there are reports that children have been abused and mistreated by other detainees and/or security guards and these young people are especially vulnerable because jurisdiction and protocol for child protection is not always clearly defined in detention centres.

The inability to protect their children from any of this is an additional trauma on parents and has resounding impacts on family relationships. Many times parents are kept separate from their children and allowed to “visit” with them. Parents reported “anguish at not being able to provide for the basic needs of their children”.

Researchers have found that for parents, the restrictions in immigration detention can impact on parents’ capabilities to care for their children. They are unable to make choices around nutrition and schooling, and in some situations, where they are housed in separate units, not able to sleep close to them.

This, in combination with long periods of uncertainty and parents’ experiences of persecution, war, violence and exhaustion, can have detrimental impacts on the relationships between these parents and their children.

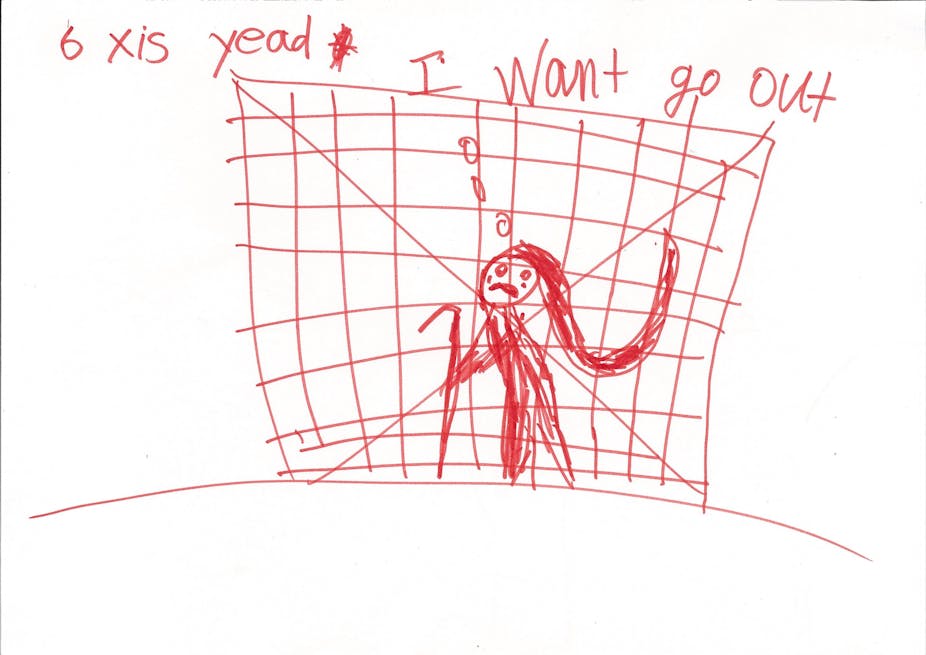

Children have historically had inadequate educational provision in immigration detention compared to those with similar needs in the Australian community. Reportedly, there are situations where young people have been denied things such as crayons in detention because “the children might draw on the walls”. The regular movements from facility to facility reported by families, adds further disruption to the opportunities these children do have to access education.

In a visit to the Christmas Island detention facility, the AHRC remarked that overcrowding had lead to the education wing being used for accommodation and that the high numbers of detainees meant that many children could not attend the local island school because there was not enough space.

These are trapped children and parents who have little opportunity to access the rights that should be afforded to them by the international conventions that protect us all. It is in the interest of everyone that notice is taken.

Elizabeth Elliott, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health, Sydney Medical School at University of Sydney

The Forgotten Children. Three words that encapsulate the fate of children forcibly detained in Australia’s immigration detention centres. Children stripped of their identity and denied the basic human rights of freedom and education. Vulnerable children, many suffering post-traumatic stress disorder, with mothers who have lost hope. Children who have, for many months, remained invisible to the average Australian.

Invisible, inaudible and forgotten. That is, until the advent of the 2014 Australian Human Rights Commission’s National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention.

The inquiry’s report finally gives asylum seekers and their children a voice. It humanises the children and it helps us to visualise their plight. The report provides tangible, credible, quantitative evidence to underpin observations reported by clinicians, including me, who’ve visited detention centres – on the mainland, Christmas Island and Nauru – and those who provided submissions to the inquiry or appeared at hearings.

It highlights the harms – to health, mental health and well-being – that result from detention in hostile, inappropriate settings.

In March 2014, at the start of the inquiry, more than 1000 children under 18 years (153 under four years, 336 primary school-aged and 196 teenagers) had been held in arbitrary detention in centres in mainland Australia, Christmas Island and Nauru – for more than eight months on average (now more than 17 months), in violation of international human rights law.

Among these children we documented mental health disorders sufficient to warrant treatment in 34%, a level that wildly surpasses the 2% of the general child population who use outpatient mental health services. More than 30% of children surveyed report being always sad or crying; 25% are always worried; 18% sleep badly or have nightmares; 12% eat poorly; 4% self-harm.

The severity of their mental ill-health was measured using a validated tool, the Health of the Nation Outcomes Scales for Children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA). This revealed moderate to severe problems across all domains measured including behaviour, mood and social skills. Specific problems with concentration, language, and emotional control and anti-social behaviour were moderate or severe in more than 10%.

Perhaps these results should not surprise, considering the toxic environment. In one 14-month period, the Department of Immigration recorded 233 assaults, 27 cases of voluntary starvation and 128 incidents of actual self-harm in children in detention. The risk of suicide or self-harm was “high-imminent” or “moderate” in 105 of these children, ten of them under the age of ten. Add to this mix the mental ill-health of their parents and detention cannot but provide a bad beginning in life for child detainees.

We acknowledge the government’s efforts to decrease the number of children in detention, but have a duty of care to those who remain. We must also provide ongoing assessment and treatment to minimise long-term health and mental health outcomes for those living in the community. In future, the detention of children must not be arbitrary, should be a measure of last resort, and must be for the shortest possible time. Our evidence confirms that the longer the duration of detention, the worse the outcomes.

The report flags the urgent need for Australia to release all remaining child detainees into the community and to consider legislative change to ensure we manage children differently into the future. As a society we owe it to all children, in or out of detention to offer compassion, humanity and the health care and education that is their right.

Note: Elizabeth Elliott travelled to Christmas Island as part of the ARHC’s inquiry. Read her account here.

Madeline Gleeson, Research Associate, Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at UNSW Australia

International law is clear on the circumstances in which detention will be arbitrary and unlawful. Detention, whether of asylum seekers or anyone else, is prohibited unless it is “reasonable, necessary and proportionate to a legitimate purpose”.

This “legitimate purpose” is the linchpin. The purposes that may justify detention of asylum seekers have traditionally been constrained to initial identity, health and security checks, and a few other specific grounds. More recently, there has been debate about whether these grounds could be expanded to include deterring irregular migration.

The Human Rights Commission’s inquiry renders this debate moot.

In evidence to the inquiry, former immigration ministers Scott Morrison and Chris Bowen admitted on oath that detaining children does not deter either asylum seekers or people smugglers. In conceding this point, they undermined the purported “legitimate purpose” that successive Australian governments have relied on to justify mandatory detention. In the words of the ARHC:

… there appears to be no rational explanation for the prolonged detention of children.

The tests of reasonableness and necessity require that detention be based on a detailed assessment of the necessity to detain, taking into account the circumstances and needs of each individual, and possible alternatives to detention.

When a child is involved, international law demands an even higher level of protection. The best interests of each child must be assessed individually and taken into account as a primary consideration, and no child should be detained except as a last resort. This final requirement is also enshrined in the Migration Act.

Australia’s current regime does not comply with any of these obligations. No real best interests assessments are conducted, nor are less restrictive arrangements considered for any child. Detention itself is causing harm, as children are exposed to assaults, sexual assaults and self-harm. 34% of detained children have mental health disorders so severe as to require hospital-based outpatient psychiatric treatment, compared to 2% in the Australian community. Children on Nauru in particular are:

… suffering from extreme levels of physical, emotional, psychological and developmental distress.

These findings are unequivocal. The detention of Australia’s “forgotten children” will not “stop the boats”. But it will cause potentially irreversible harm to young people in our care, many of whom may become Australian citizens one day.