When Rex Tillerson, the former CEO of Exxon Mobil, was confirmed by the US congress, he agreed to sever all ties with the world’s largest publicly traded international oil and gas company.

But of course that didn’t summarily erase the relationships he has built with leaders of oil-producing countries, which stand to influence his tenure.

Before joining the Trump team, Tillerson had no experience in government, the military or as a public servant. But he knows his world and is well-known on the international stage.

Having worked his way up through different positions in Exxon since 1975, he became Chairman and CEO in 2006. This position provides a familiarity with international diplomacy, expertise in managing large operations, and skills negotiating with global leaders.

Or, to quote Trump:

These features could make Tillerson the Trump administration’s ace card, bringing an extraordinary understanding of the role oil plays in the world – particularly in Russia and China – and of how to rebuild American political power in the global arena.

But conflicts of interest could haunt his term. Tillerson has close ties to Russia: in 2013 president Vladimir Putin granted him the Order of Friendship award, and a recent leak revealed that he once served as director of the Bahamas-based US-Russian oil firm, Exxon Neftegas.

His relationship with Venezuela, the world’s 11th ranked producer of crude, was more fraught. How will a Tillerson-run State Department engage this crisis-stricken, oil-rich South American country?

Exxon and Venezuela: a rocky road

ExxonMobil’s history in Venezuela starts in 1921, when its predecessor, Standard Oil, set up shop there. What’s happened since, particularly during the governments of the so-called “Socialism of the 21st Century” under the successive administrations of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, does not necessarily augur well for bilateral US-Venezuela relations under Tillerson.

Venezuela’s ties to ExxonMobil were severed in 1976, when president Carlos Andres Pérez sought to nationalise the oil industry. They were reestablished in the 1990s when Pérez, in his second term, launched the so-called “Apertura Petrolera” (“oil opening”), seeking to attract foreign investment and develop the Orinoco oil belt.

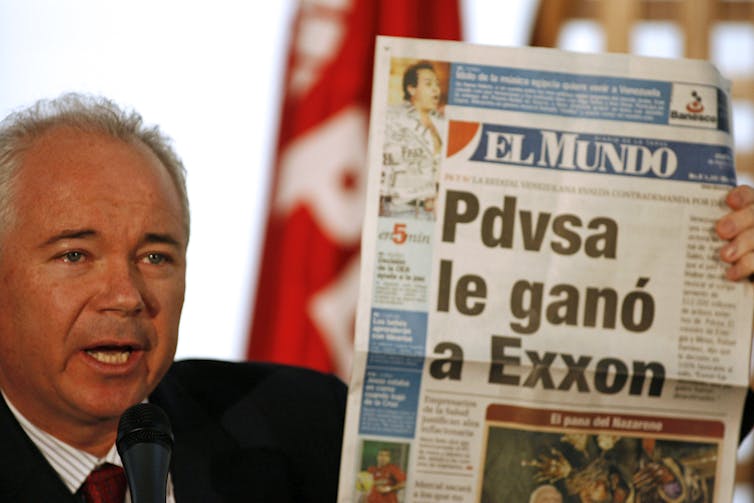

But when Hugo Chávez decided to re-nationalise the oil business in 2007, Venezuela’s state oil company, PDVSA, acquired a majority stake in domestic oil ventures. ExxonMobil, by now under Tillerson’s leadership, rejected the government’s offer to pay book value for its assets, countering with a request for arbitration by the World Bank’s investment disputes settlement centre. ExxonMobil aimed to receive market value for its investments, assessed at US$15 billion.

In 2014 Venezuela was ordered to compensate ExxonMobil $US1.6 billion.

Another problem arose in 2015, this time under Maduro, when ExxonMobil launched oil operations off the coast of neighbouring Guyana. That area lies very close to Venezuela’s Delta Amacuro state, in the Essequibo territory over which Venezuela has asserted ownership for more than a century.

In 2000 and 2002 the Venezuelan government brought claims to the World Petroleum Congress about Guyana’s proffered concessions in the Essequibo. International companies were initially compelled to cease drilling, but in 2012 operations resumed. Today both countries are seeking a peaceful agreement to this old border dispute with the UN Secretary General.

Meanwhile, Esso Exploration and Production Guyana Ltd, an ExxonMobil subsidiary, has declared that it will continue developing the region, which is part of a US$200 million, ten-year contract between Esso and the Guyanese government.

Maduro has accused ExxonMobil of trying to destabilise the region by siding with Guyana, while ExxonMobil has complained about the Venezuelan government trying to turn countries against the company.

Oil and the Venezuelan crisis

Venezuela is now facing the worst chapter of history since its 19th century civil war, and is experiencing a major humanitarian crisis – despite having enjoyed the greatest oil boom of its history during the first decade of this century.

The weaknesses of Venezuela’s economic model – a political-ideological project in which the country was able to leverage oil to buy domestic and international support – have been brought into stark perspective.

After dismantling the private domestic productive apparatus (creating absolute dependence on oil exports) and weakening state institutions, Venezuela now has insufficient fiscal revenues, massive debt, a debilitated currency on the road to hyperinflation, scarcity of basic products – plus skyrocketing crime, legal insecurity, political imprisonments, social unrest, and so on.

Despite the terrible situation that’s now worn on for over a year, there is no sign of policy correction. The Maduro government blames an imperial economic war, wherein the US is highly culpable, along with the local oligarchy.

In September, US Secretary of State John Kerry, who supported the 2014 sanctions levied against Venezuelan officials (not general economic sanctions), expressed concern. “We’re very, very concerned for the people of Venezuela, for the level of conflict, starvation, lack of medicine,” he said.

Political bluster or business pragmatism?

A possible future Secretary of State Tillerson could take one of two paths.

Traditionally, Tillerson and ExxonMobil have been against economic sanctions as international policy. But a historically troubled relationship with Venezuela, coupled with its anti-American discourse, could nonetheless bring about an aggressive US stance toward Venezuela.

This might include increasing sanctions against Venezuelan officials (similar to those currently in force until 2019), severing diplomatic relations or suspending or significantly reducing Venezuelan oil purchases. Any of these measures would further devastate the country’s already critical economic situation and increase the Maduro government’s international isolation.

Given Tillerson’s experience and negotiating mastery, however, it is feasible that he could see beyond the radical left-wing discourse. He might compel Venezuela to honour its international financial commitments and act pragmatically given its situation, by privatising confiscated unproductive industries, reducing the mandatory 60% PDVSA national ownership in all oil projects and ending price controls for domestic production.

In this scenario, the US and Venezuela might even reach an agreement to alleviate domestic food and medicine scarcity.

In the first scenario, Tillerson’s ExxonMobil proclivities are set aside in the service of a relationship based on hard principles and American values of the sort the incoming US president has said he seeks to resuscitate. In the second, the pragmatism and traditional interests of international business – that is, Tillerson’s own instincts – may predominate.

Which path will Tillerson follow with Venezuela? We’ll have to wait for his attention to turn southward to find out.