Fraud. It’s an ugly word, an arresting word. As with “cheating” it comes loaded with negative connotations, but can potentially lead to far greater penalties and consequences. And yet fraud in science is not unheard of.

The world of economics was shaken two weeks ago by the revelation that a hugely influentual paper and accompanying book in the field of macroeconomics is in error, the result of a faulty Excel spreadsheet and other mistakes – all of which could have been found had the authors simply been more open with their data.

Yet experimental error and lack of reproducibility have dogged scientific research for decades. Recall the case of N-rays (supposedly a new form of radiation) in 1903; clever Hans, the horse who seemingly could perform arithmetic until exposed in 1907; and the claims of cold fusion in 1989.

Medicine and the social sciences are particularly prone to bias, because the observer (presumably a white-coated scientist) cannot so easily be completely removed from his or her subject.

Double-blind tests (where neither the tester and the subject know for sure whether the test is real or just a control) are now required for many experiments and trials in both fields.

Deliberate fraud

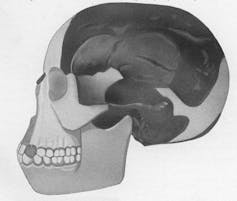

Of even greater concern are proliferating cases of outright fraud. The “discovery” of the Piltdown man in 1912, celebrated as the most important early human remain ever found in England, was only exposed as a deliberate fraud in 1953.

An equally famous though more ambiguous case is that of psychologist and statistician Sir Cyril Burt (1883-1971). Burt’s highly influential early work on the heritability of IQ was called into question after his death.

After it was discovered that all his records had been burnt, inspection of his later papers left little doubt that much of his data was fraudulent — even though the results may well not have been.

Perhaps the most egregious case in the past few years is the fraud perpetrated by Diederik Stapel.

Stapel

Stapel is/was a prominent social psychologist in the Netherlands who, as a November 2012 report has confirmed, committed fraud in at least 55 of his papers, as well as in ten PhD dissertations written primarily by his students.

(Those students have largely been exonerated; though it is odd they did not find it curious that they were not allowed to handle their own data, as was apparently the case.)

An 2012 analysis by a committee at Tilburg University found the problems illustrated by the Stapel case go far beyond a single “bad apple” in the field.

Instead, the committee found a “a general culture of careless, selective and uncritical handling of research and data” in the field of social psychology:

[F]rom the bottom to the top there was a general neglect of fundamental scientific standards and methodological requirements.

The Tilburg committee faulted not only Stapel’s peers, but also “editors and reviewers of international journals”.

In a private letter now making the rounds, which we have seen, the 2002 Nobel-winning behavioural economist Daniel Kahneman has implored social psychologists to clean up their act to avoid a potential “train wreck”.

Kahneman specifically discusses the importance of replication of experiments and studies on priming effects, wherein earlier exposure to the “right” answer, even in an incidental or subliminal context, affects the outcome of the experiment.

There are certainly precedents for such a “train wreck”.

Perhaps the best example was the 1996 Sokal hoax, in which New York University physics professor Alan Sokal succeeded in publishing a paper in Social Text, a prominent journal in the postmodern science studies field.

Following publication, Sokal revealed he had deliberately salted his paper with numerous instances of utter scientific nonsense and politically-charged rhetoric, as well as approving (equally nonsensical) quotes by leading figures in the field.

He noted that these items could easily have been detected and should have raised red flags if any attempt had been made to subject the paper to a rigorous technical review.

Needless to say, the postmodern science studies field sustained a major blow to its credibility in the wake of the Sokal episode.

Regrettably, if unsurprisingly, the Stapel affair is not an isolated instance in the scientific world.

Moriguchi and McBride

We previously discussed the following case on The Conversation:

In October 12 2012, the English edition of the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun reported that “induced pluripotent” stem cells (often abbreviated iPS stem cells) had been used to successfully treat a person with terminal heart failure.

Eight months after being treated by Japanese researcher Hisashi Moriguchi, supposedly at Harvard University, the front-page article emphasised, the patient was healthy.

The newspaper declared that this was the “first clinical application of iPS cells,” and mentioned that the results were being presented at a conference at Rockefeller University in New York City.

But a Harvard Medical School spokesman denied that any such procedure had taken place.

As it turned out, Moriguchi’s results were completely bogus, as was his claimed affiliation with Harvard. There were certainly reasons to be suspicious of this report.

Moriguchi claimed to reprogram stem cells using just two specific chemicals, but prominent stem-cell researcher Hiromitsu Nakauchi responded that he had “never heard of success with that method,” and, what’s more, that he had never heard of Moriguchi in his field before this week.

Within seven days Moriguchi had been fired by the University of Tokyo.

Another instance closer to home is the case of Australian medical researcher William McBride, who was one of the first to blow the whistle on the dangers of thalidomide in the 1960s, but in 1993 was found guilty of scientific fraud involving his experiments with another anti-morning sickness drug, Debendox.

Clearly the scientific press completely failed in exercising due diligence in such cases – but how many other such cases have eluded public attention because of similar systemic failures?

If we believe the maxim “where there is smoke, there is fire”, it is clear that scientific fraud may be on the increase.

Why do scientists and other academics cheat?

So why do scientists cheat? And, also, why are scientists sloppy? Of course, scientists are people, fame is fame and money is money, but some other possible answers are listed below.

Deliberate or unintended bias in experimental design and cherry-picking of data. Such effects run rife in large studies funded by biotech and pharmaceutical firms.

Academic promotion pressure. Sadly, “publish or perish” has led many scientists to prematurely rush results into print, without careful analysis and double-checking.

This same pressure leads some to publish papers with relatively little new material, resulting in plagiarism and self-plagiarism.

And who could forget the cases of Annette Schavan and Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, the two German cabinet ministers forced to resign in recent years over plagiarism accusations over work done during their doctoral theses. (The PhD is highly prized in German public life.)

Overcommitment. Busy senior scientists can end up as co-authors of flawed papers that they had little to do with details of. One famous case is that of 1975 Nobel Prize winner David Baltimore, regarding a fraudulent 1986 paper in the journal Cell.

Ignorance. Despite American biologist E.O. Wilson’s recent protestations to the contrary, many scientists and most clinical medical researchers and social scientists know too little mathematics and statistics to challenge or even notice inappropriate use of numerical data.

Self-delusion. Clearly many scientists want to believe they have uncovered new truths, or at least notable results on a long-standing problem. One example here is the recently-claimed proof of the famed “P vs NP” conjecture in complexity theory by the mathematician Vinay Deolalikar of HP Labs in Palo Alto, California, which then quickly fell apart.

There appears to be a mathematical version of the Jerusalem syndrome, which can afflict amateurs, cranks and the most serious researchers when they feel they have nearly solved a great open problem.

Confirmation bias. It sometimes happens that a result turns out to be true, but the data originally presented to support the result were enhanced by confirmation bias. This is thought to be true in Mendel’s seminal mid-nineteenth century work on the genetics of inheritance; and it may have been true in early experimental confirmation of general relativity by Eddington and others.

Deadline pressure. One likely factor is the pressure to submit a paper before the deadline for an important conference. It is all too easy to rationalise the insertion or manipulation of results, under the guise that “we will fix it later”.

Pressure for dramatic outcomes. Every scientist dreams of striking it rich, publishing some new result that upends conventional wisdom and establishes him/herself in the field. When added to the difficulty in publishing a “negative” result, it is not too surprising that few scientists feel motivated to take a highly critical look at their own results.

Leading journals such as Nature and Science are not without sin. in 1988, Nature‘s great editor John Maddox managed to publish a totally implausible paper on homeopathic memory in water.

In 2010, Science played games with its own embargo policy to get maximum publicity for an arsenic-based life article by a telegenic NASA-based scientist that fell apart pretty quickly.

- Quest for research funding. Scientists worldwide complain of the huge amounts of time and effort necessary to secure continuing research funding, both for their student assistants and to cover their own salaries. Is it surprising that this pressure sometimes results in dishonest or “stretched” results?

Granting agencies and their political masters are also culpable. All funded research must be rated hyperbolically as “world-class,” “leading-edge,” “a breakthrough,” and so on. Merely “significant,” “careful” and “useful” are not enough.

- Thrill? Some scientists are apparently driven by the pure thrill of getting away with cheating. At the least, it is clear that some, including Stapel, take some pride in outwitting their peers. Like any addiction, what may start out as marginal misbehaviour can grow explosively over time.

In most cases it is clear that those perpetrating scientific fraud, as with those of compromised integrity in various other fields, did not wake up and say: “I’m bored. I think I’ll write a fraudulent scientific paper today.”

Instead, just like Ebenezer Scrooge’s deceased partner Jacob Marley, they forged their chains “one link at a time”.

Indeed, this appears to be the case with Stapel: a detailed recent article about Stapel in the New York Times indicates a slow progression from scrupulous to bizarrely unscrupulous.

In his own words, Stapel grew to prefer clean if imaginary data to real messy data.

One of the saddest and oddest cases is the honey-trap set by Russian/Canadian mathematician Valery Fabrikant. Fabrikant translated papers he had solely authored in Russian years earlier. He then added the names of senior academics in Engineering at Concordia University in Montreal — who did not demur.

When they did not buckle to his threats of blackmail, and he was refused tenure, Fabricant went on a rampage. He is currently in jail for the 1992 murder of four “innocent” faculty members at Concordia.

What can be done?

Clearly academic fraud — while still the exception not the rule — is a complicated problem, and many systemic difficulties need to be addressed.

But one major change that is needed is to move more vigorously to “open science,” wherein researchers are required (by funding agencies, journals, conferences and peers within the community) to release all details of approach, data, computation and analysis, perhaps on a permanent website, so that others can reproduce the claimed results, if and as necessary.

Another form of fraud occurs after publication. All metrics regarding citations are subject to massage.

A stunning example of manipulation of the impact factor (a measure reflecting the average number of academic citations) by editors is to be found in the 2011 article Nefarious numbers, which lays out the methods that can be employed by those who wish to do so.

In Australia, it seems clear bibliometrically-driven assessment exercises such as Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) are likely to exacerbate the pressures on academic (and other) institutions to “bulk-up” their dossiers.

Additionally, as The Australian pointed out last year, it is potentially dangerous, especially for junior staff, to be whistle-blowers.

Moreover, current law in many countries impedes full investigation of academic misconduct and leaves accusers open to a legal suit.

Fraud will not disappear – it is part of science, and life in general, however infrequent and undesirable. The best we can do is develop better ways to identify it, address it and move on.

Further reading: When things don’t add up: statistics, maths and scientific fraud

Apology to Professor David Copolov

An earlier version of this article contained an incorrect claim regarding Professor David Copolov. This claim was entirely untrue and it has therefore been removed. We apologise to Professor Copolov without reservation.