If I were a fashion designer, I would create a line of contemporary secular mourning clothes.

Why? Lately, I have been thinking a lot about social mourning. Many of my students are now at the age (mid-to late 20s) when they are experiencing the passing of their grandparents. As I try to accommodate their mental and emotional fragility with the requirements of keeping up with their classwork, I realise that today’s secular social systems do not adequately address mourning as a social process. The only recognition of social mourning that one finds in Australian society is the workplace policies regarding Aboriginal “sorry business” and Torres Strait Islander “sad news”.

When anthropologists talk about death, the values they associate with mourning rituals consist of:

(1) finding out the cause of death;

(2) ensuring that the dead moves to his or her next state of existence or non-existence; and

(3) taking care of the surviving family and friends so that they are not pulled by their connection to the dead loved one into death as well.

Mourning clothes play a crucial role in the third value by making visible the chief mourners so that other members of society can offer them the emotional support that they need.

The design of mourning clothes traditionally focuses on colour and fabric texture.

Colour is often the first social indicator of mourning status. Both academic books like Lou Taylor’s Mourning Dress and popular blogs on the colours of mourning discuss how black is the main colour of mourning in Europe and countries strongly influenced by Europe, including most of North America and Australia. Taylor describes how Benedictine monks introduced black for mourning during the sixth century as they associated the colour with “spiritual darkness of the soul”. The wearing of black mourning clothes reached its height during the Victorian era when Queen Victoria enshrined for over 40 years a national culture of mourning at the death of Prince Albert.

In my neighbourhood of Greek migrants and their descendants, elderly Greek women continue to wear black dresses to symbolise their mourning for their former spouses.

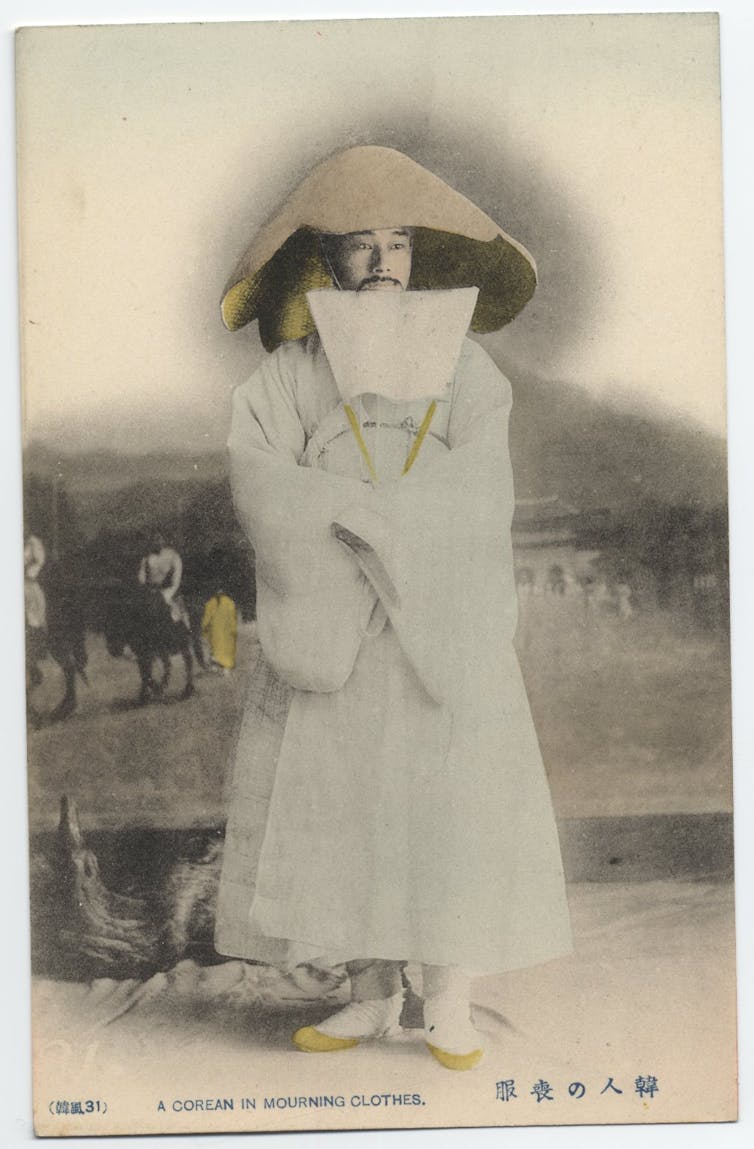

In much of Asia (e.g. China, Korea, Japan, and Hindu India), white is the colour of mourning. According to the Chinese Five Elements principles, white is the symbol of “the unknown and purity”. Since death is part of the unknown and once a person is dead his or her soul is assumed to be pure again, it is considered the appropriate mourning colour.

Red, purple, blue, brown, grey, and even yellow have served as colours of mourning for different spiritual beliefs, nations, classes and genders of people throughout history. Regardless of the specific colour, Taylor and others state that spiritual intent of the colour of mourning clothes is to “hide mourners for the attentions of evil spirits,” and thus keep them from being carried off by death as well.

While colour represents the spiritual aspects of mourning, the fabric of mourning clothes conveys more secular concerns regarding the display of both the humility and the social status of mourners at the same time. Queen Victoria made silk crepe the fashionable veil and trim of the mourning dress for women. The dullness of its sheen demonstrated the mourners humility. But as Kyshan Hall notes, the fabric often needed to be replaced because it would disintegrate in the rain. The dresses themselves were to be made of specific silks and linens. The expense of mourning clothes often proved an economic burden for many middle and lower class Victorians, who found more inexpensive fabrics or dyed and redyed dresses while attempting to maintain an air of respectability.

Traditionally in Korea, the white mourning gown would be made of coarse hemp fabric.

Art curator Min-Sun Hwang describes how in ancient Korea farmers, servants, and middle class women, but never nobles, wore hemp during the hot summers. Based on a 9th century C.E. legend of filial piety, its choice as the fabric of mourning was “a symbolic act intended to ‘pay’ for this loss and to compensate for the fact that the children had outlived their parents.” The wearing of a full hemp gown is not as common in today’s fast-paced urban centres in South Korea. Yet deeply tied to Confucian beliefs, these practices continue in the rural towns and villages.

Traditionally, the experiences of wearing mourning clothes form part of the general restrictions in movement for mourners, with at least a week of confinement in the home. Religious and spiritual mourning periods can last from one month to two years, depending on the cultural context and the relationship of the mourner to the dead. During this time, it is assumed that the mourners are too distraught to be able to function in everyday life. Mourning clothes make visible to others that lots of time is required in which one must socially support mourners. Jana Riese, in a blog post for the Huffington Post, recognises this. She says, “Mourning clothes gave people permission to take time to grieve … I am betrayed by the very notion that the world outside my window dares to go on as usual. I ought to dress accordingly.”

But it is important to also recognise that the wearing of mourning clothes was and continues to be highly restrictive of the movement of widows, especially in societies where the widow is seen as the potential cause of death of her husband. In October, both Time and the BBC ran articles on the economic vulnerability of white-dressed Hindu Indian widows, who have been reduced to begging for their livelihood.

With this warning about the potential abuse of women made more visible by their mourning clothes, there is something valuable about providing people ample time for mourning that is lacking in today’s secular social systems and offering the opportunity to “dress accordingly”. What would it mean to design contemporary secular mourning clothes that marked people’s stages of grief so that you can appropriately respond?

Nel Verbeke and Rasa Weber, two German design students at the Design Academy Eindhoven, offer a vision of contemporary secular mourning clothes through their project Ritual Skin. They describe their clothes as representing a three-phrase process of:

Dissolving: the first shock of loss is a sudden and very emotional moment. A thin layer of textile dissolves just by beweeping the ones we have lost.

The peeling: there is a very conscious and deliberate aspect in detaching from a person. Step by step we are peeling away a skin of leather from our shoulders.

The monument: in the end a monument in the form of warm wooden shell is decently remaining, as we can never overcome a loved person.

The students’ clothes are more poetic than practical, but they speak to a need to redesign secular society’s approach to mourning. Contemporary secular mourning clothes could be the first tangible steps in realigning society’s values more closely to mourner’s experiences. The outcome of this redesign would be the better accommodation of the mental and emotional fragility of those who have to un-do their connections to the dead, so as to not join them.