Inequalities between men and women persist in many areas, with women still earning less than men on average. An even more striking difference is the “motherhood pay gap” that happens when women have children. Also known as the “family gap” or child penalties, women’s earnings plummet after the birth of a child, while men’s barely budge.

Many studies have investigated the causes of gender inequalities and concluded that women have been unable to catch up to the earnings level of men in part because of parenting responsibilities.

Why does this happen? Children have a negative effect on women’s productivity in the labour market by substantially reducing their human capital, which translates into a significant decrease in their earnings.

After the birth of children, mothers tend to turn towards part-time jobs, roles with flexible working hours or positions that offer work conditions more favourable to family life — all of which tend to pay lower wages.

Employers, in return, may see part-time employees as less committed and productive, especially when relying on heuristics — mental shortcuts for solving problems — to judge worker quality, as opposed to actual information about their performance. This can result in fewer bonuses and promotions for these employees.

The effects of parenthood

Evidence from Denmark, one of the most egalitarian countries in the world, points to a long-term child penalty of around 20 per cent in earnings.

Our research reveals a similar situation in Canada. We used data from Statistics Canada’s Longitudinal and International Study of Adults coupled with historical administrative records from 1982 to 2018.

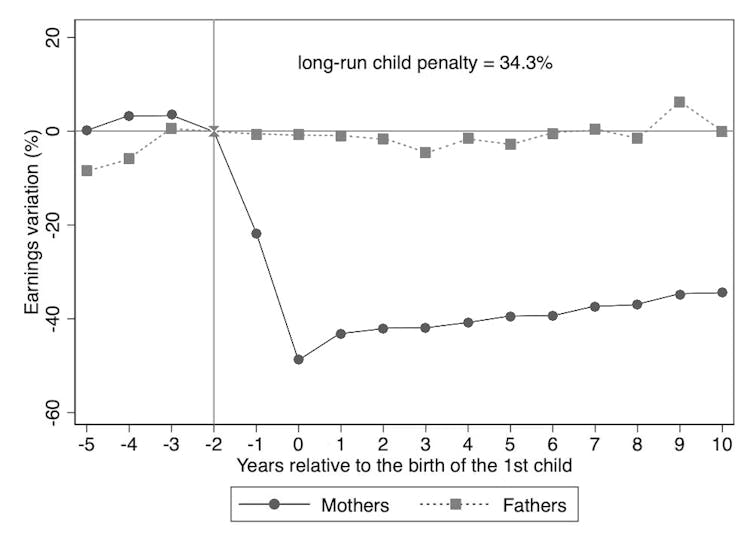

We compared what happened to men’s and women’s earnings after the birth of their first child for Canadians who had their first child between 1987 and 2009. Using an event study methodology, we followed individuals’ employment income over a period of five years before the birth of the child to 10 years after.

We observed large and persistent negative effects of parenthood for mothers, but not fathers. Mothers’ earnings decrease by 49 per cent the year of birth, with a penalty of 34.3 per cent 10 years after. Fathers’ earnings appear largely unaffected.

Unequal effects of children

The birth of children results in large earnings losses that are not equally distributed within heterosexual couples. Fathers stay on the same earnings track, while women experience penalties that persist over the years. This is especially true for mothers of multiple children or those with a lower education level.

This impoverishment triggered by the birth of a child can have significant economic impacts should the couple separate. In Canada, nearly one-third of marriages end in divorce.

Women are typically financially disadvantaged following a separation. This disadvantage may be attributable to pre-separation factors, such as the unequal division of labour during the marriage and lower earnings for women, but also to women’s prolonged absences from the labour force due to family responsibilities.

Equal pay for equal work

In this context, it’s crucial to ask ourselves if there are measures that could eliminate, or at least reduce, the economic impact associated with family responsibilities on mothers’ earnings and employment.

We investigated the role of family policies, since they were in part designed to encourage maternal employment and promote more equal sharing of parenting responsibilities between partners.

Specifically, we focused on the extension of parental leaves in Canada and the introduction of reduced contribution child-care services for families in Québec. We found suggestive evidence that these policies can help reduce child penalties.

“Equal pay for equal work” policies, such as the federal government’s Pay Equity Act, also have the potential to make a substantial difference. These policies can raise the fairness and attractiveness of the labour market for women and reduce the potentially negative impact of experience-based pay for mothers.

More benefits down the line

In addition to having a positive effect on the economic situation of women, encouraging employment for mothers could help eliminate the stigma around the division of labour within couples by exposing children to a more symmetrical model of remunerated and unpaid work.

A recent study using data from 29 countries showed that employed mothers were more likely to transmit egalitarian values to their children both at work and at home. Girls with employed mothers ended up working more themselves: they worked more hours, were better paid and held supervisory positions more often than girls with stay-at-home mothers.

The result was not observed in boys. However, boys who grew up with employed mothers were more involved in family and domestic responsibilities as adults than men whose mothers were not in the labour market. The girls also spent less time doing household chores.

Working mothers appear to have an intergenerational impact favouring gender equality, both within the family and in the labour market.

We all know raising children is time-consuming. Children, of course, benefit from this parental time investment. But bringing up children is also costly. Our research quantified one kind of cost: the lower earnings trajectory. Knowing how these costs are shared among the two parents is key to enable better decision making, for policymakers, but ultimately, for parents, future parents and their children.